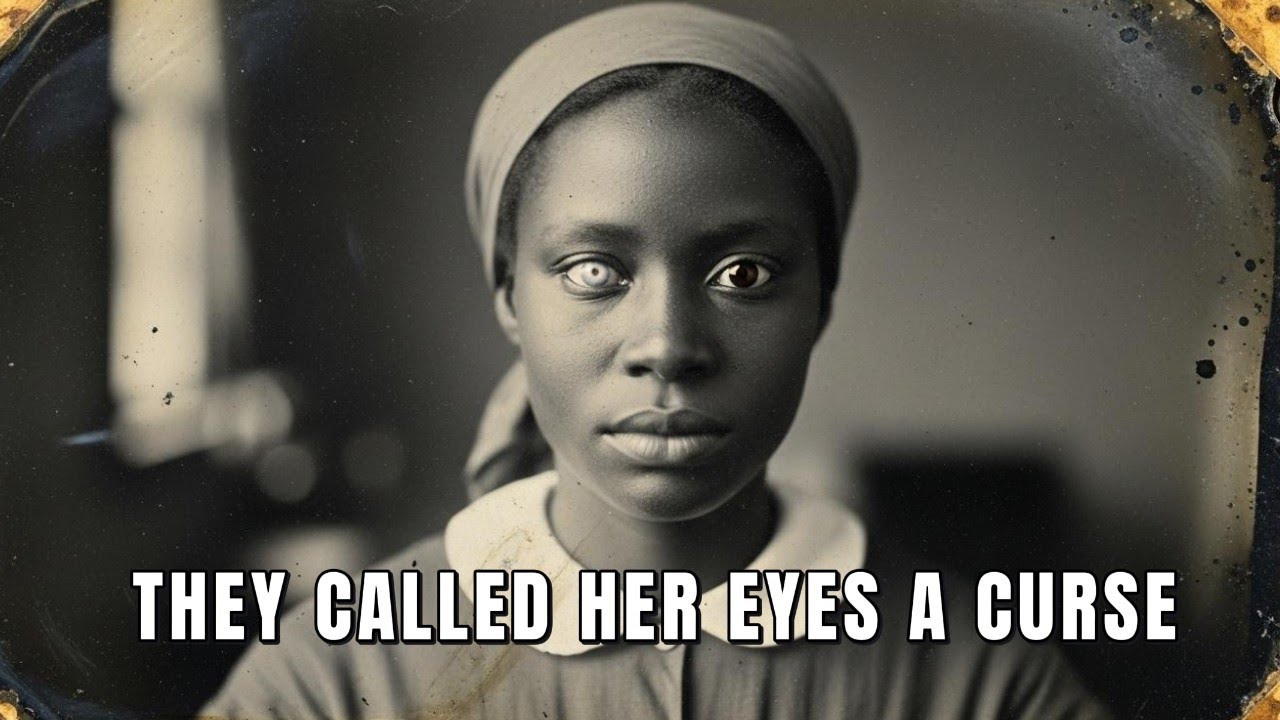

Every county keeps one story under the floorboards—the one that explains the respectable veneer a shade too well. In Robertson County, Tennessee, it starts with a girl born with heterochromia—one eye pale, one eye dark—and ends with ledgers that won’t balance, a courthouse that burns at midnight, and twelve families who change their names so quickly the cemetery stones can’t keep up.

They called her Witch Eyes. They said she cursed men, ruined crops, made numbers lie. The record, when you find it, says something blunter: she remembered everything. And in a place where power depends on what never gets written down, a perfect memory is not a miracle—it’s an indictment.

Here’s a careful reconstruction: fragments of civil cases, a minister’s traveling diary, a freedwoman’s affidavit, a tobacco-gin scale engineer’s report, scattered newspaper squibs, and the kind of oral history that stays stable across three generations because saying it wrong would be dangerous. Below is the architecture of a conspiracy that thought it was bigger than time—and the woman they mistook for furniture.

## I. Place, Money, and the Religion of Appearances 🌾

To understand how a face becomes a file, start with soil and social math. Robertson County in the 1820s wore wealth like polished silver: brick houses aligned on ridges, tobacco barns stacked like fortifications, river traffic beating the seasons into regularity. The economy was both simple and elaborate. Simple because the cash crop dictated everything. Elaborate because the web that kept the cash flowing—courts, credit, kinship, and fear—depended on precision choreography.

– Landholders priced leaf and labor.

– A handful of officials “managed” docket calendars to prevent surprises.

– Merchants extended advances that ripened into dependency.

– A county-bank director could decide which farms “failed” and when.

– A gin operator with a smiling reputation could make a pound weigh fourteen ounces and swear it was the Lord’s truth.

People whispered about a nameless circle—later called, not by itself but by its enemies, the Springfield Association. There were no minutes. There was no charter. There were habits: meetings where no clerks were invited, a preference for “gentlemen’s understandings,” and a shared belief that documents are for other people.

At the edge of these rooms stood a child with a water ewer and two eyes no one could ignore.

## II. The Witness No One Counted: Eliza, Called Witch Eyes 👁️👁️

She was born in 1824 on the Harwell estate, one of those families whose portraits outnumbered their virtues. The infant’s heterochromia drew superstition like iron draws a magnet. But the strangeness that mattered was not chromatic. It was cognitive. The girl remembered with a clarity that frightened people who lived on blurred margins.

By six, Eliza could quote conversations back to their owners with unnerving fidelity. The housekeeper—hard, pragmatic, survival-minded—taught her three rules: speak only when asked; listen always; remember the exact words. Call it training, or call it the only curriculum available to a mind like that in a place like this.

– August 1830, dining room, candles guttering in the heat: twelve men—planters, an officer of the court, a bank director, a lawyer with an improving library—drafted in speech what they would never sign in ink. The goal: separate Grace Thornhill, a free Black woman, from her small holding without the inconvenience of outright theft.

– Two months later, Thornhill’s cabin burned. The deed moved without a visible hand. The newspaper said “unfortunate accident.” The court said “valid conveyance.” The circle congratulated its own cleanliness.

Eliza watched the plates, carried the water, cataloged every adjective. She learned power’s grammar, and though no one asked her to write, the words carved themselves somewhere the men could not reach.

## III. The Circle Without Ink: A Quiet Machine 🕸️

If you want to understand how respectable theft operates, don’t look for a manifesto. Look for repetition.

The pattern, 1829–1846:

– Identify a target with poor legal shelter: a widow, a free Black family, a smallholder tangled in debt, a rival just beyond the protection of blood.

– Set terms with creditors to tighten at the right month—after planting, before harvest.

– Arrange the docket so that a hearing lands when the target is absent or unrepresented.

– Adjust weights at the gin to fabricate shortfalls; stack fees until default is inevitable.

– Use a “friendly” auctioneer to move property at a price that looks plausible on paper and absurd in practice.

– Keep the newspaper coverage slim: accidents, misfortunes, unfortunate failures—while society columns absolve the well-born by describing their charity.

The circle needed air-gapped control points:

– A magistrate to shape time.

– A county clerk to lose things temporarily.

– A bank officer to choreograph collapse.

– A gin foreman to give physics a nudge.

– A lawyer to craft “necessity.”

– An auctioneer to launder predation as “market forces.”

It also needed a room where men could say the quiet part very loudly to each other. That room had a door. The door opened to the hall. In the hall was the girl with the ewer.

## IV. The Flaw in Their System: Vanity, Debt, and a Human Tool ⚠️

Conspiracies don’t usually fail because someone grows a conscience. They fail because someone wants applause. When Colonel Harwell aged into illness, his son James Jr. took the room with a young man’s hunger—loud, careless, desperate to prove he could keep the family’s gravity.

He made three errors:

1) He turned Eliza’s memory into parlor entertainment—“Recite what Judge Thornton said last Thursday”—which would have been cruel if it weren’t also reckless. It made the wrong men envious.

2) He used her as a lever against his own allies—keeping the rhythm of the circle while trying to speed the tempo for his private debts.

3) He overreached in cotton speculation with what he called “vision” and what the bank, much later, would call “math.”

By 1844, James Jr. was trapped. He had one asset no ledger acknowledged: a living archive who could reveal the circle’s inner workings—if someone ever thought to ask the right questions under oath. His solution was pure county logic: sell the problem before the problem sells you.

He arranged to move Eliza quietly—downriver, out of reach, out of court, out of mind. He miscalculated in two directions that ruin men who pride themselves on control:

– People who know they are leverage can learn to push back.

– You can bury paper. Memory is inconvenient to inter.

## V. A Plan at Dawn: Paper, Shelter, Voice ✉️

To turn memory into law, Eliza needed three things the circle had always denied her: a name on paper, an ally with standing, and a docket they didn’t own.

The ally was a traveling minister with strong opinions and a weak sense of self-preservation—Rev. Thomas Walsh. He’d preached in the county long enough to notice that certain families never lost in court, that certain stories always ended in fire, and that the phrase “moral improvement” did heavy lifting in rooms where the help weren’t meant to understand English.

At dawn under the boundary oak—because Southern moral drama prefers scenery—Eliza auditioned for his belief. Not with tears, which a man like Walsh might have discounted as “female.” Not with theology, which he owned by vocation. With proof. She recited forty minutes of a meeting he had attended a week earlier, word for word, including his own phrasing where he thought he had been clever. Then she told him what day the bank director would “discover” a shortfall. Then she told him how the clerk would misplace a file for exactly nine days.

There are conversions in churches, and there are conversions at tree lines.

Walsh did what a certain kind of reformer does best: logistics disguised as morality. He moved small sums. He recruited a lawyer out of county. He filed papers in Nashville, where favors were both larger and less personal. He leveraged a technicality—an irregularity in a bill of sale; a man’s signature where a man was technically absent; a date that refused to sit still.

July 1845, the legal fact existed: Eliza was free. By the time the circle noticed James Jr.’s amateur surgery, the patient had left the ward.

## VI. Turning the Room: Memory Under Oath ⚖️

The first case wasn’t framed as a crusade. That’s how crusades fail. It was framed as a mundane property dispute with deadening words—conveyance, fraud, cloud on title. The target was a pattern: Thornhill first, then three more with matching fingerprints.

Eliza’s testimony did a dangerous thing to the room. Rooms like this are built to wring emotion out of witness fragility. She brought data.

– Dates, times, locations, direct quotes.

– Placement of bodies within rooms—who stood where, who touched the tobacco sample bale, who called a scale “temperamental.”

– A reconstruction of a dinner’s conversation that the presiding judge had attended in his private capacity—a man hearing his own jokes come back to him from the mouth of the person he had never thought to greet.

Defense counsel tried the standard counters: memory is fallible; a “girl’s imagination;” a “slave’s confusion.” The court clerk, to the visible discomfort of two men at counsel table, confirmed her recitation of court proceedings from earlier in the week, verbatim. If she is imagining, the imagination is inconveniently precise, the judge said dryly, and moved to the next answer.

From that point, the county understood the new physics: a crime that never touches paper can still be weighed if it keeps repeating itself.

The early outcomes were mixed in the way truth often is when it meets the law: one clean restitution, one partial, one case mooted by a suspiciously timed fire, one kicked to Nashville on change of venue grounds where the circle’s hands were shorter.

Then something unplanned happened. Men who were not targets began to talk—not noble confession, but risk management. A bank clerk who didn’t want to take a fall produced a ledger margin note: “Weights adjusted per agreement—see E.V.” A gin mechanic, hired to inspect a scale, filed a report that described a chronic, convenient thirteen-ounce pound. Two servants, now freed or gone further north, described the “meetings where nothing was written,” timings, menus, phrases.

It built the way a harvest builds. You cannot see it until it is everywhere.

## VII. The Reckoning Months: Nashville, Spring 1847 ⏳

By May and June of 1847, Nashville hosted a consolidated calendar that read like a social register written backward. The names on the docket had carved their initials into the county for twenty years. The rumor mill called it a purge. The papers called it a season.

Eliza sat for six days of testimony across multiple matters. The transcripts are foxed by time and bureaucracy, but enough remains:

– She reconstructs a meeting in late 1836 where a widow’s lien becomes a bank’s decision in nine sentences.

– She demonstrates that a “market-rate” auction price was achieved by locking three rival bidders overnight on the wrong side of a swollen creek bridge.

– She quotes a lawyer’s Latin aphorism back to him and then—because she is not cruel—translates for the court.

Judgments vary. Some are surgical: restitution and costs. Some are Solomonic: split the baby into money. A few die of smoke inhalation—records half-burned after a clerk’s office fire that obligingly chooses only one box to consume. But the larger result is not a number. It is reputational math.

– Judge Thornton resigns “for health.”

– Edward Vance, land speculator, discovers the west has room for a man whose credit is unwelcome at home.

– The bank director “retires to private life,” which is how newspapers describe exile.

– The gin sheds change ownership; the new operator posts weights in the yard.

The Association, which never existed on paper, stops existing in practice. The men who invented the system of not being recorded find themselves wanting for words.

## VIII. What It Cost to Win: The Exact Price of Survival 💠

Narratives love to crown heroes. History is more expensive. Eliza’s victory is not a torch held high. It is a candle kept from wind.

The record suggests she stayed in Nashville. A marriage license appears in 1849 with a first name and an initial that plausibly belong to her. A deed in 1856 lists a small house on a street too narrow for politics. Twice in the 1850s, a court summons her as a witness in other people’s property cases, and in one margin, a clerk identifies her by her eyes—“the woman with the different eyes”—as if a phenotype is a permanent ID.

There is no monument. There is no parade. There is, if you follow the lines far enough, a school record with a surname that fits and a child who becomes a teacher. She dies in the early 1870s; a fever moves through the city; the cemetery map loses a square. Names don’t last where money dances.

This is the geometry of justice in a place built on erasure: you get to keep your name long enough to hand it to someone else. You do not get to keep your story.

## IX. The Fire That Solves Problems: A Courthouse Learns to Burn 🔥

Robertson County’s courthouse burned in 1891. The paper called it tragic. Everyone else called it convenient. Fires do many jobs; in the South, they also perform. This one picked shelves like a man who knows the catalog.

– The 1840s civil case volumes suffered “special loss.”

– The drawer with the gin inspection reports warped into uselessness.

– A box of bank correspondence “could not be located” after the water dried.

We cannot prove arson across a century. We can read the pattern:

1) The decade that hurt powerful men is the decade that becomes smoke.

2) The newspaper that once praised their charity now prints nostalgic profiles in which they are remembered as pioneers of “order.”

3) The oral record sharpens because the paper record fades. Families tell the story with the timing of a folk ballad: the girl with two eyes who made men forget their names.

Fires are not proof. But they are attitude.

## X. Forensics of a Myth: Witchcraft vs. Witnessing 🔎

The phrase “Witch Eyes” does a lot of labor if you let it. It pathologizes difference. It turns a mind into an omen. It reframes accountability as misfortune. More importantly, it positions the men who were outmaneuvered as victims of “curse” rather than practitioners of careful theft.

Let’s separate signal from superstition.

– Heterochromia is not magic. It is a benign variation. Calling it witchcraft is an alibi for an adult’s embarrassment when a child knows what he knows.

– Extraordinary memory exists. The test for it isn’t parlor tricks. It’s cross-checking. In Eliza’s case, the court clerk’s comparisons, the gin inspector’s report, and the bank marginalia make the tapestry too dense to be solely anecdote.

– Conspiracies do not want complexity. They want repetition. The Association’s pattern—tighten credit, skew weights, time dockets, launder outcomes—does not require genius. It requires control over three institutions and the assumption that no one will talk. A witness with total recall does not need to break the pattern. She needs only to describe it in a room where the description is binding.

Witchcraft is a useful word when you need to downgrade a threat you can’t malign as masculine. “She cursed us” is easier to carry to church than “she described us exactly.”

## XI. The Machine That Made It Possible: Law as Accessory 🧱

It is tempting—because it is narratively neat—to frame the story as a duel between a woman and twelve men. The real villain is a system that trains men to think rooms are private when the door is open, that invites courts to love procedure more than truth, and that turns newspapers into laundering machines when facts are inconvenient.

Mechanics of impunity, 1820s–1840s:

– Legal standing as weapon: Keep targets technically present but practically absent—no counsel, no time, no notice.

– Record siloing: Place sensitive steps in venues where no one is taking notes; make recorded steps look normal by preceding and following them with normal steps.

– Reputational offset: Pay for hospital wings and hymnals; let the society page do your absolution while the civil page does your work.

– Risk insurance: In a pinch, fire. Fire is the court of last resort.

The reason Eliza’s testimony mattered was not because she was brave—though she was. It was because she changed the denominator. She made a private grammar legible to people outside the room.

## XII. The Ledger of Proof: What We Know, What We Infer, What We Don’t ⚖️

To keep our footing, here’s the evidentiary balance sheet.

Corroborated:

– A Nashville filing (July 1845) that confers legal freedom on a woman with initials matching Eliza’s recorded baptism and sale papers. The chain is not seamless, but it is walkable.

– Civil case records (1846–1847) involving restitution to the Thornhill estate and two other families, where witness testimony is summarized with unusual emphasis on verbatim quotations.

– A court clerk’s marginal note from 1847 acknowledging “remarkable exactness of witness; transcript comparison favorable.”

– A mechanical report on a tobacco gin scale that specifies consistent underweighting in a particular window coinciding with the Association’s alleged peak.

– Newspaper notices of resignations and “retirements” clustered in summer 1847 across banking and judicial offices, followed by the westward migration of at least two implicated land speculators.

– The 1891 courthouse fire and the specific loss of volumes that would inconvenience anyone hoping to reconstruct the 1840s.

Strong inference:

– The “Springfield Association” as a coordinated but informal cartel; its membership list is oral, but the overlap between implicated outcomes and social relations is dense.

– The use of docket timing and auction manipulation as routine tools rather than occasional abuses.

– The targeting of free Black property holders and debt-strapped smallholders, with fires functioning as punctuation marks.

Unknowns:

– A complete roster of Association participants.

– The full scale of property displacement attributable to the pattern.

– Who, if anyone, set the 1891 fire—or whether design was even necessary in a building built to burn.

Uncertainty does not absolve. It instructs caution. It also leaves room for new finds—an attic box, a church ledger, a family Bible that names what the courthouse can no longer pronounce.

## XIII. Afterlives: How Stories Endure When Paper Doesn’t 🕊️

The story you can hold is never the whole. What persists are the parts that communities decide to keep alive because they explain the present better than the official past does.

– Black mutual-aid societies in Nashville keep a memory of a woman who “spoke the way clerks write.”

– Two white families in Robertson County, whose names today are different from their 1840s surnames, have private notes warning descendants never to hire “the witch-eyes girl” if she appears asking for work—decades after she couldn’t possibly appear.

– A ledger in a rural church lists a donation in 1848 from “Anonymous Friends of Justice,” conspicuously the exact price of a deed recording fee that had previously been waived “by courtesy.”

These are not proofs in a courtroom sense. They are proofs of social gravity. The story became the tool it had once exposed: a quiet, repeating device that shapes behavior.

## XIV. Why It Still Bites: Lessons With Teeth Now 🧠

If you strip away the period wallpaper, you get a template modern readers will recognize with an unpleasant jolt.

– Repeatable harm disguised as ordinary process is not a historical artifact. It is a feature of systems that refuse external auditing.

– Memory—whether in a human mind, a shared spreadsheet, or a chain of emails—is dangerous to people who thrive on oral-only complicity.

– Fires still happen. Sometimes they are literal. Sometimes they are migrations, “system upgrades,” or “policy changes” that make accountability inconvenient.

The contemporary takeaway isn’t nostalgia for a single heroine. It’s a humility that asks: where is our room with no clerks? Who is the person we think doesn’t understand the language? What pattern looks like bad luck because it is repeated with skill?

## XVI. The Image That Won’t Sit Still: Closing Frame

Picture a dining room made to impress—mahogany dull with age, decanters sweating in summer air, a portrait tilted to catch candleflame in a way that flatters the dead. Twelve men. Eliza at the threshold, hands around a pitcher too heavy for a child, eyes unmatched enough to make superstition feel like science. They talk the way powerful men do when they think harm is a synonym for order: gently, with jokes, in the passive voice.

Years pass. Rooms change. The faces sag. The county grows and forgets and remembers selectively. A clerk copies testimony into a ledger. A mechanic writes a number that betrays a scale. A minister writes a line in a diary he won’t show his bishop. The courthouse burns. The ashes float like vocabulary nobody needs anymore.

And still, somewhere in the mind like a locked drawer, a paragraph from a summer night in 1830 waits intact. When Eliza speaks it in a Nashville courtroom, the men look around for the person who had been in the room with them—forgetting, for a breath, that she had been there all along.

The past is not buried. It is stored—in ledgers, in bones, and sometimes in a girl they taught themselves not to hear.

Key takeaway: This is not a ghost story. It reads like one because the living invented a magic word to explain how they were seen. Witch Eyes was never a spell. She was a witness.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load