The night the board came up, the house had the listening quiet of a home that expects news. Clara worked a palette knife under the crack—one eye on the lamp flame, one ear on the river—not because she loved prying at old wood but because the joist had begun to complain when the children crossed it. The mill’s whistle had gone silent an hour earlier, a soundlessness that made the town feel like it had misplaced something essential. Beneath the board: dust, a nail that had volunteered to retire, and a ledger wrapped in cloth that used to be red.

If you want a single image to explain how a person becomes a force, there it is: a widow bent over her floorboards, deciding whether to open a book that might ask her to become someone the town has not practiced accommodating. The year was 1902. The town was Ashton Falls, Maine—a mill village whose map could be sketched by anyone who had ever been paid by the week: river, dam, brick rectangle of a factory, boardinghouses, church, company store, green where summer pretended life was simpler. The Merriweather Paper and Twine Company was a local fact the way the river was—a power you scheduled your day by.

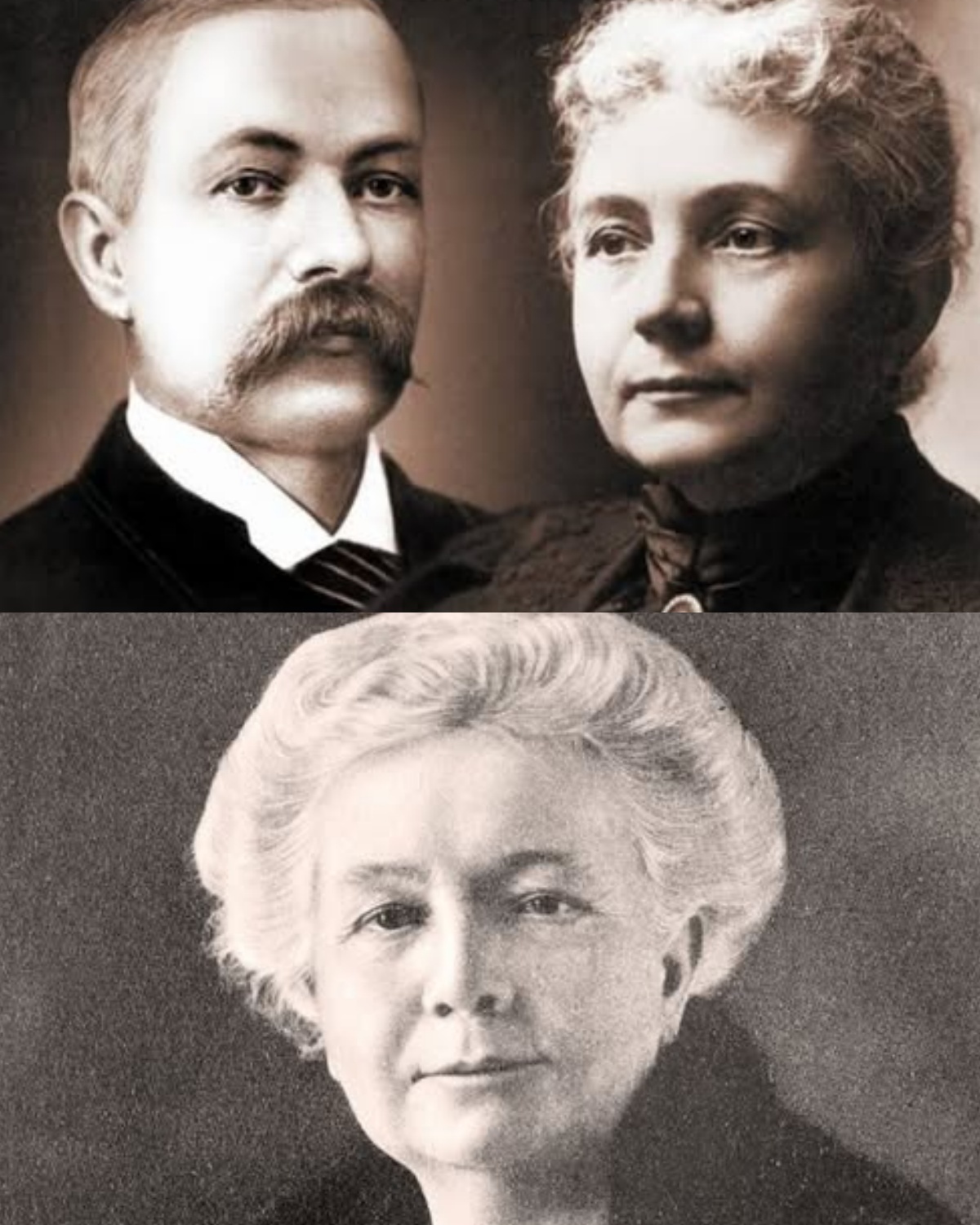

Clara, born Clara Finch in 1869 in a farmhouse where the wind had more opinions than the men, had married Thomas Merriweather with what the neighbor women called “eyes open.” She could add a column faster than most men could lay a length of line, and when Thomas, genial and better with people than with subtraction, brought home ledgers in the early years, she sharpened her pencil and protected his optimism from arithmetic. “If hope wants to be use,” she wrote in a diary line that survives because her granddaughter traced it with a felt-tip pen a century later, “it must answer to numbers.”

Thomas died as men do in mill towns—a small accident promoted by bad luck into a fatality. A belt snapped. A pulley let go. The doctor noted “blunt trauma” and wrote “regretfully” in a hand trained to be tidy in the face of chaos. The minister spoke kind words about industry and Providence. The insurance assessor, who had a face that looked like it had never had to keep anyone else’s child fed, asked Clara to sign a form that underlined “widow” twice. She signed, then wrote “bookkeeper” in the margin, because words instruct people how to behave toward you.

The ledger under the floorboards was not there by accident. Thomas had hidden it. The cloth around it smelled faintly of the sweetish sour of mill oil. Clara untied the knot. Inside: columns that did not match the public books. Shipments marked in pencil that never became ink in the official records. Payments to a name that had appeared only once in her kitchen—a man with good boots and a soft hat brim who had called himself “an investor with interests in water rights.” Beside his initials: numbers that marched at a brisker pace than any factory crew could sustain without a strike. A note in Thomas’s hand: “Discuss after reorg.” The page trembled in hers, not because she was given to drama, but because the tremor had the sincerity of hunger and the mill was how she fed five children.

You can spend a whole life being told where you belong and still find yourself a mile past the signpost. The town expected Clara to sell—in pieces if necessary, the way a mare becomes harness and glue and a set of brass buckles. The bank manager, who had known her as a careful woman with a good hat and exact change, pivoted to the voice he used for a certain class of widow. “The papers will fetch a fine price,” he said, tapping the company’s patents with a ring that meant something once. “There’s no shame in it.” She looked at his ring and thought about how metals learn their dignity by pressure, not by speech.

In the days that followed, the town developed a habit of speaking to her as if she were a weather vane—an instrument that reports direction but does not change it. The foreman came by with his cap in his hand and a list of men who wanted to know if Friday would still mean pay. The union—new enough to be self-conscious when it used its own name—sent a delegation that included a young man with a scar that made him look serious even when he grinned. The rival syndicate, the one with interest in “consolidation for efficiency,” sent a letter on paper expensive enough to have opinions, offering what it called relief and what the river called theft. Clara read everything and then sat at the kitchen table with the ledger on one side and the children’s copybooks on the other, as if intellect and appetite could be negotiated into family.

Her diary—kept on cheap paper, entries brief and occasionally sharpened into something like a sentence fit for print—says, “July 18: All advise sale. Thomas’s hidden book suggests siphon. Payroll must be met.” A second line, in pencil faint as a whisper: “If there is a way, do not ask blessing—evidence.”

Evidence arrived in a coat smelling of coal: a traveling auditor named Harper, retained by the bank “to facilitate a dignified wind-down.” He wore his courtesy like a vest. Clara watched him perform a few gentle sums and realized he was measuring not capacity but compliance. When he suggested that she sign a power of attorney “to ease signature burdens,” she said, “I have two hands,” and set a neat stack of meal tickets beside the ledger as if to remind him what arithmetic feeds. He smiled the way a man smiles when a dog barks at the moon. “This is men’s business,” he said. “It will be, if you insist,” she replied, a sentence that years later would be quoted at a historical society luncheon with the kind of applause women give each other when history has begun to apologize.

The town paper, the Ashton Falls Evening Clarion, hedged its bets in editorials that managed to sound chivalrous and nervous at once. “Mrs. Merriweather, a lady of estimable character, faces the hard calculus of modern enterprise,” one piece read. “We trust Providence will guide her to a decision pleasing to her late husband’s memory and to the stability of our town.” The printer, who also set union notices on the quiet, inserted the word “her” in italics the second time it appeared, a tiny act of mischief that managed to feel like a neighbor’s hand on your elbow.

There are moments in a life when the definition of respectable behavior shrinks or stretches like wool under hot water. Clara’s moment arrived with the man in the soft hat brim returning, this time under his own name: Tillinghast, with papers that made “interests in water rights” more than a euphemism. He represented Consolidated New England Mills, which understood rivers as a kind of currency and used small towns as ATMs. “We can remove risk,” he said. He meant: we can remove you. She poured coffee and listened. Listening is not the same as agreement. When he showed her a map of the river with a new dam drawn in as if water would be flattered by lines on paper, she made a sound in her throat that the youngest child later remembered as the one she made when a pot boiled over.

It took a week to learn the ledger’s grammar. Thomas had been paying someone to keep the books generous where the payroll was concerned. That generosity had cost him credit in the circles where men prefer profit to loyalty and had invited the bank to keep a stricter hand on the leash. The siphon—the payments to Tillinghast’s initials—was a tax on dignity disguised as a partnership. Clara was not scandalized. She was practical. “Every house has a line where the rain finds its way,” she wrote. “You can curse the roof or learn the route of the water.”

She learned the route. She found the clause in the original charter—written in lawyer Latin and old-fashioned belief—that allowed the mill to float a community loan secured against future profits if a majority of workers endorsed the plan. It was a relic from a time when men still remembered what it felt like to build something with neighbors. The bank had forgotten the clause. The union’s secretary, a schoolteacher’s son with good penmanship, had not. Together, they drafted a notice: “Proposal for Share Subscription: Wages guaranteed; profits distributed quarterly; layoffs only by joint consent; oversight by a board elected from floor and office.”

This is the part of the story that the local histories summarize too neatly, as if a town simply nodded and rearranged itself into virtue. The truth, in the documentary clutter that a granddaughter would later file in acid-free folders, looks more like a week of combustion. The foreman grumbled about “women with ideas.” The union debated whether profit-sharing was a seduction in a decent dress. The bank manager sent a letter warning of “irregularities.” The Clarion printed an anonymous piece questioning whether a woman’s “domestic energies” might be wasted in “the masculine arena of iron and steam.” A letter to the editor signed “MG, mother of three” answered with a sentence still quoted at town meetings with a mixture of pride and amusement: “Sir, my domestic energies have been known to boil a potato and a man’s temper at the same time.”

Clara moved through the days as if timing were a kind of doctrine. She visited the boardinghouses where the single men tried to look like citizens in rooms the size of closets. She sat with wives who kept strawberry jam like a sacrament. She stood on the green on a Sunday, after the minister’s wife had given the children lemonade and advice, and explained the plan as if she were teaching long division: “If we do this together, nobody outside decides how hungry our children are.”

The doctor—who had set Thomas’s body down as carefully as a book borrowed from a friend—sent a note that began, “I cannot advise in business” and ended, “I am ready to testify that sudden unemployment is deleterious to the health of infants.” He could not say politics. He could say bronchiolitis. The note went in the file marked “arguments that count.”

In September, under a sky that had decided to be clear as if to deprive everyone of an excuse, the vote took place. The union hall smelled of pine soap and tobacco, like a forest that had taken up a bad habit. Ballots folded and slipped into a box that had once held spools. It was close enough to make the room hold its breath. When the tally tipped, someone shouted, not a word, just a sound like a valve releasing. The headlines were cautious. The Clarion chose “New Arrangement at Merriweather Mill; Community Plan Adopted.” The Boston papers preferred “Woman Leads Novel Scheme; Shares Control with Workers.” Tillinghast preferred a letter from a lawyer.

The letter accused her of interfering with existing contracts. It threatened injunctions and the kind of suit that strips a person of hours and leaves them in debt to the calendar. She laid the letter on the kitchen table beside the ledger that had started this pivot and the children’s school notices. “They fear losing the river,” she wrote. “They will try to drown me in paper first.”

She answered with paper of her own. Patents that Thomas had filed for a machine that trimmed waste from the edges of paper rolls—small efficiencies that make men in distant rooms smile. A new application for a binding twine formula that resisted moisture—useful if you lived in a climate that found dampness charming. Letters from grocers who preferred a supplier who delivered on time and in person. Minutes from a union meeting promising “orderly conduct and no stoppage during retooling.” A petition from town mothers—fifty signatures in ink that wandered like conversation—saying, “We like knowing who bakes our bread and pays for the flour.”

The case had enough law in it to keep several men employed and enough sentiment to make the same men fear a jury. It never went to trial. Tillinghast, whose hat brim had lost some of its softness, made a winter visit and set his palms on Clara’s table as if to warm them. “You have made an impression,” he said, which is the kind of sentence men use when they have decided to accept a new fact while regretting the need. They struck an agreement that would look, to someone seeking heroes and villains convenient as chess sets, like compromise. It allowed the mill to operate without consolidation. It set a percentage of profits aside for debt and for replacing belts before they betrayed a man’s head. It guaranteed wages through winter. It required, and this is the detail the grandchildren loved to underline, a woman’s signature on any material change to water rights.

The next two years belonged to the grind disguised as grace. The mill worked. Paper went out, twine went out, money came in in amounts that felt like relief and proof. The foreman discovered that he liked explaining improvements to a woman whose questions had the courtesy of accuracy. The union discovered that voting on oversight felt less like sedition and more like adulthood. The doctor discovered fewer cases of “exhaustion” when men knew they would not be made beggars by a slow season. A visiting writer for a Boston weekly came to town and produced a piece that confused adjectives with admiration. “The Widow Merriweather,” it called her, without ever naming her as anything else, “has led her men to water and taught them to swim.” Clara clipped the piece and then corrected the margin in pencil: “We taught each other.”

It would be lovely, for the sake of the arc that sells to school assemblies, to report that everything after was dinner and dividends. The record refuses that pleasure. A worker lost a hand to a careless second—the new guard bent a little, a habit uncorrected by oversight. A small fire in the carding room reminded everyone that fiber is tinder with ambition. A strike in a neighboring town sent pamphleteers through Ashton Falls with slogans that flattered and threatened in equal measure. The minister’s sermon the following Sunday, on “pride and prudence,” was admired for its even hand and criticized for the same.

What did change, in ways that paper can show, is how a town described itself. A school essay from 1905—kept because the teacher found it funny and because the boy grew up to be the kind of man who pays for archives—reads, “My mother says Mrs. Merriweather is the boss. My father says we are all the boss. I say the river is the boss because it is loudest.” A line in the union minutes notes, “Motion: to allocate 2% of quarterly profit to a sick fund; passed.” An advertisement in a seed catalog lists “Merriweather binding twine—reliable,” a word that in a town where men used to stand in front of a mill door on Mondays with their hats on their heads instead of in their hands meant something more than marketing.

The high point, the one the local history puts in bold, arrived in the summer of 1906 when a flood tested the dam and the dam tested everything people had decided to believe about themselves. It started with rain the way disasters do in places where rain is a personality. The river climbed its banks, polite at first, then with a confidence that dared the town to remember other springs when fences floated. The dam—rebuilt three times in the half-century since the first men in boots and hope decided to tell water what to do—took the strain until it didn’t.

At three in the morning, the watchman—a man with a limp that let him know when a storm was honest—rang the bell that would later be hung in a municipal museum with a plaque that fails to convey how anxious metal can make you feel. Men woke. Women woke men who slept harder than they should. The foreman rounded up a crew with rope and a mania for living. The physician arrived with a bag and the kind of face that makes children angry at how unafraid grown-ups can look. Clara arrived in a coat that did not know whether to be black for grief or brown for work. She carried the ledger because once you have allowed a book to change your life, you bring it along when life tries to change you back.

The breach was not dramatic enough for a painting. It was a seam opening, a thread pulled wrong. The river found the flaw and widened it the way a rumor widens into a rift. Men hauled, swore, slipped, recovered. Sandbags were a theory in a story until they weren’t. Someone sang a hymn without the words, which is the best way to sing when the words are busy elsewhere. The union secretary, the one with good penmanship, led a line of boys with shovels who looked serious enough to make a photograph that would make their grandchildren cry later without knowing exactly why.

Tillinghast arrived at dusk, which is when men accustomed to negotiation prefer to arrive, as if gray light can bless ambiguity. He brought engineers who nodded in unison and a plan that had the merit of being possible and the flaw of requiring the town to surrender certain rights in exchange for immediate expertise. “We can help,” he said, with a face that expected gratitude and got arithmetic instead. Clara, who had learned to count not just coins but costs, asked him to step aside to a place where the river could shout over both of them. “If you help now,” she said, “you do so as neighbors. If you require papers signed in the dark, you will be remembered accordingly.” It was not a threat. It was a kind of banking with memory instead of money.

The dam held enough of itself together to allow the town to claim survival without bragging. The mill reopened in a week, a miracle owed less to Providence than to tired men and women who had decided to be their own weather. The Clarion printed an editorial that managed to be both grateful and sly: “We thank our friends from away for their concern and reserve also the right to remain ourselves.” Tillinghast’s engineers left with the professional disappointment of men whose expertise has been partly declined. He left with a new respect he would not admit to at his club.

There is a photograph from that week everyone remembers without having seen. People describe it as if it hangs in a hallway they walk daily: Clara on the dam wall, a notebook open, hair under a hat that thinks it knows the wind, the foreman pointing at something the camera cannot record, boys with shovels trying to look like men and succeeding for an hour. The photograph exists, sort of—blurred, overexposed, rescued from a shoebox the day the house on Maple Street changed hands. A granddaughter, sorting papers in a summer when nostalgia paid better than consulting, taped the photograph into an album and wrote beneath it, “The day the river learned our names.”

Clara did not live to see factories metamorphose into museums or mills into condominiums with names that pretend work is a rustic aesthetic. She died in 1919, influenza greedy and indiscriminate, the doctor’s ledger thinning into the white of paper he had not wanted to waste on the words he wrote too often that year. Her death certificate lists “occupation: manager.” The Clarion gave her a full column that repeated the sentence about her hands and signatures and added a line about her laugh that makes you like the editor. The union minutes record, “A motion to place flowers on her grave; passed unanimously.” The bank manager retired in 1921. He kept, on his desk, her first subscription notice, framed under glass like a penance he chose to find instructive.

What remains, besides a park where children throw bread to ducks with the gravity of priests, are papers and voices. A ledger wrapped in cloth that used to be red. A diary with the sentence about hope and numbers. Union minutes that learned to make space for adjectives like “fair” and “enough.” A letter from Tillinghast, years later, congratulating the town on paying off its community loan—“an experiment,” he still called it, as if naming could make the past less decisive. A granddaughter’s box with labels written in a hand familiar enough to make you think time is a circle: “Clara—business,” “Clara—personal,” “Clara—unanswered.”

There are ambiguities that the papers refuse to be bullied into resolving. How much did the hidden ledger indict Thomas? Enough to make your throat go tight when you remember him tinkering with belts and optimism. How much of the flood could have been prevented by earlier investment? Enough to make you wish the dam had learned to speak more plainly. Did Tillinghast ever intend to be the town’s enemy? The letters make him complicated—vain, competent, a man who loved the idea of systems because people unsettled him. Did the profit-sharing plan make anyone rich? No. It made people less poor with a reliability that felt like a kind of wealth.

A modern historian with a taste for policy papers and a secret soft spot for micro-histories teaches this story to undergraduates who expect steel tycoons and get, instead, a woman with a ledger and a river that prefers its own mind. He shows them the clause in the charter. He shows them the subscription list with nicknames that feel like affection. He plays them a recording of a town hall from the 1970s in which an old man—one of the boys with shovels then, a slow walker now—says, “We did not save the mill. We saved our faces in the mirror.” The students, who have been told they are inheriting a world of systems with appetites, take notes as if pen strokes could be anchors.

We like to make such stories smaller or larger than they are, depending on what mood history has left us in. The smaller version folds Clara into a category: early woman executive, local color, the way a county fair ribbon makes a chicken seem like a symbol rather than a bird. The larger version makes her a heroine of myth, a figure carved from the wood of American exceptionalism with a blade sharpened by romance. The honest size is the size of a human decision repeated steadily enough to become culture: she opened the ledger; she asked the town to read it with her; she declined to be rescued at the price of being erased; she taught the river her name and listened when it said it would be obeyed only to the degree that they respected it.

Late in her life—when influenza was still an unlearned word and the children were grown enough to raid the pantry without shame—Clara wrote a line inside the back cover of the diary her granddaughter would one day trace in felt-tip for a school project that made a town exhibit itself to itself. “The board I pried up creaked again today,” she wrote. “I left it. Not every complaint needs repair. Some you keep so you remember to step light.” It reads like wisdom dressed as housekeeping, which is to say it reads like a woman who has been required to make metaphors portable.

Standing in the park now, if you choose to visit, you can count ducks and sunlight and the ribs of the dam that survived the particular ambitions of 1906. There is a plaque that mentions a flood and a “notable woman” and a partnership between labor and management that “proved instructive.” It is wording that satisfies committees. It does not satisfy the itch of the question Clara’s ledger still asks: What do you do when the numbers tell you that the future requires you to be braver than the present has made room for?

A quote, saved because it fits in a pocket and in a century: A worker at her funeral was heard to say, “She did not make herself our mother. She made us our own men.” A granddaughter, grown old enough to be a grandmother herself, added when she donated the ledger to the town archive, “She showed us how to stand together in a place that taught us to line up.” Between the two quotes is a town, a river, a ledger wrapped in red cloth, and the creak of a floorboard that reminds you to put your weight where it will do more good than harm.

So here is the modest question that outlasts floods and ledgers and syndicates with hats that remember their owners: When you find, beneath the neat floor of your ordinary life, a book that asks you to become larger than the house that hides it—do you open it? And if you do, who will you invite to read it with you, and whose signatures will you insist are required before the river agrees to carry you forward?

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load