He was dying of tuberculosis at 32, coughing up blood in a Swiss sanatorium—so he wrote a pirate adventure for a bored twelve-year-old boy that invented everything we know about pirates today.

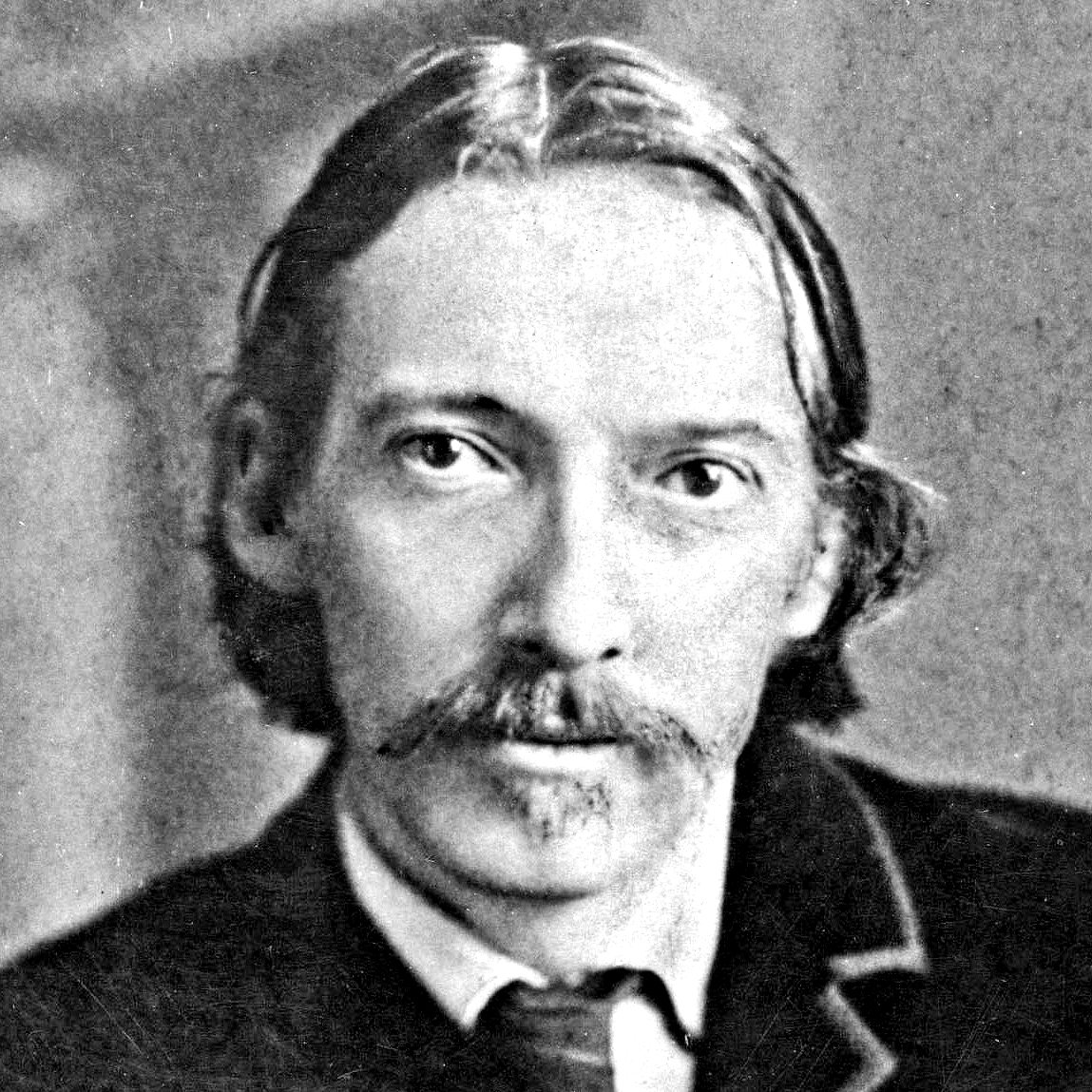

Robert Louis Stevenson wasn’t supposed to live past thirty.

He’d been sick his entire life—chronic respiratory problems, fevers, hemorrhaging lungs. Tuberculosis was slowly killing him, and in the 1880s, there was no cure. Doctors sent him to Switzerland, to the mountains where the air was supposedly healthier, where he could rest and hope his body didn’t completely fail.

He was 32 years old, broke, and coughing up blood.

So naturally, he decided to write the greatest pirate adventure ever told.

Born in 1850 in Edinburgh, Scotland, Robert Louis Stevenson grew up as a sickly child in a wealthy family. His father was a lighthouse engineer—respected, successful, and completely baffled by his son who wanted to be a writer rather than follow the family profession.

Young Louis (he went by his middle name) spent much of his childhood bedridden, reading voraciously because he was too weak for physical activity. His imagination became his playground—he’d create elaborate fantasy worlds, stage plays with toy soldiers, and lose himself in adventure stories.

His parents expected him to grow out of this childishness. He didn’t.

He studied law to please his father but never practiced. Instead, he traveled when his health permitted, writing essays and travel pieces that barely paid his bills. He fell in love with Fanny Osbourne, an American woman ten years his senior who was separated from her husband. When she returned to California, Stevenson followed her—against his parents’ wishes, despite his failing health, traveling across the Atlantic and then across America in immigrant ships and trains.

The journey nearly killed him. He arrived in California emaciated and desperately ill. But he married Fanny in 1880, and she became his fierce protector, nurse, and advocate—managing his career, rationing his energy, and keeping him alive when his lungs threatened to give out entirely.

By 1881, Stevenson had published some essays and travel writing but nothing that had made him famous or financially secure. He was 31, constantly sick, and still dependent on financial help from his father.

Then came the summer of 1881, spent at a cottage in Scotland with Fanny, her twelve-year-old son Lloyd Osbourne, and various relatives trying to escape rainy weather and boredom.

Lloyd was restless. He’d brought watercolors and was painting to pass the time. Stevenson, watching the boy, asked to see what he was drawing. Lloyd had created a map of an imaginary island.

Stevenson looked at the map and saw something Lloyd didn’t: a story.

He took the map, added more details—labeled it “Treasure Island,” marked locations like “Skeleton Island” and “Spyglass Hill,” put an “X” to mark where treasure was buried. Then he started writing, creating chapters to entertain Lloyd.

Every day, Stevenson would write a chapter and read it aloud to the household after dinner. Lloyd was enthralled. The adults—initially skeptical—found themselves caught up in the adventure. Stevenson’s father, the serious lighthouse engineer, became one of the story’s biggest fans, suggesting plot points and inventing details about Billy Bones’s sea chest.

The story was pure adventure: young Jim Hawkins discovers a treasure map, joins a ship’s crew hunting for buried pirate gold, and encounters the unforgettable Long John Silver—a one-legged ship’s cook who’s charming, dangerous, and morally ambiguous in ways children’s literature rarely portrayed.

Here’s what’s extraordinary: almost nothing in “Treasure Island” was based on historical piracy. Stevenson invented nearly all the “pirate” tropes we now consider authentic:

Treasure maps with “X marks the spot”

Pirates with peg legs and parrots

Singing sea shanties

Buried treasure

The Jolly Roger flag as a universal pirate symbol

The romanticized image of swashbuckling adventure

Real historical pirates were brutal criminals who rarely buried treasure (they spent it), didn’t sing while working, and certainly didn’t have theatrical personalities. But Stevenson’s pirates were so vivid, so memorable, that they became the template for every pirate story that followed.

Long John Silver, especially, was revolutionary. He wasn’t purely evil—he was charismatic, intelligent, genuinely affectionate toward Jim at times, yet capable of ruthless violence. He was one of the first morally complex villains in children’s literature, showing young readers that bad people could be likable, that evil wasn’t always obvious.

Stevenson wrote the entire first draft in about fifteen days—remarkably fast, driven by his desire to entertain Lloyd and his own genuine excitement about the story. He was having fun, probably for the first time in his writing career. The essays and travel pieces had been serious, literary work. “Treasure Island” was pure play.

But getting it published was difficult. It was too long for children, too adventurous for serious literature, too unconventional for Victorian sensibilities. Finally, a magazine called “Young Folks” agreed to serialize it in 1881-1882 under the title “The Sea Cook, or Treasure Island.”

The serialization was moderately successful, but not spectacular. Some readers loved it; others found it too violent for children. The magazine paid Stevenson very little.

Then in 1883, it was published as a complete novel by Cassell and Company. And something unexpected happened: it became a phenomenon.

Adults loved it as much as children. Critics who normally dismissed adventure fiction praised its vivid characters and tight plotting. It sold steadily, then explosively. Suddenly, the chronically ill writer who’d been scraping by was internationally famous.

“Treasure Island” gave Stevenson financial security for the first time in his life. More importantly, it gave him confidence. He’d proven he could write something commercially successful without compromising his craft.

He followed it with more classics: “Kidnapped” (1886), another adventure novel; “Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde” (1886), a psychological thriller that became even more famous than “Treasure Island”; and “The Master of Ballantrae” (1889).

But his health continued deteriorating. Doctors kept sending him to supposedly healthier climates—Switzerland, France, the Adirondacks, Colorado. Nothing worked. His lungs were failing, and everyone knew it was only a matter of time.

In 1888, Stevenson and Fanny made a radical decision: they chartered a yacht and sailed to the South Pacific, believing the tropical climate might help. They visited the Marquesas, Tahiti, and eventually settled in Samoa.

Remarkably, Stevenson’s health improved in Samoa. The warm climate, the outdoor lifestyle, and perhaps simply being happy in a place he loved gave him a few more productive years. He built a house called Vailima, became involved in Samoan politics, and continued writing.

The Samoans called him “Tusitala”—the teller of tales. They respected him not as a sickly foreigner but as someone who told powerful stories and treated them with dignity.

On December 3, 1894, Stevenson was helping Fanny make mayonnaise for dinner when he suddenly collapsed. He’d suffered a cerebral hemorrhage—likely related to his lifelong health problems. He died that evening at age 44.

The Samoans carried his body to the top of Mount Vaea, fulfilling his wish to be buried overlooking the sea. His tombstone bears his own poem “Requiem”:

“Under the wide and starry sky

Dig the grave and let me lie.

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I laid me down with a will.”

Robert Louis Stevenson lived only 44 years, much of it in pain and illness. But in that short, difficult life, he created stories that have entertained millions for over 140 years.

“Treasure Island” alone has been adapted into films, TV series, stage plays, and countless reimaginings. Every pirate movie, every treasure hunt story, every tale of adventure on the high seas owes something to the book Stevenson wrote to entertain a bored twelve-year-old boy.

He invented the pirate genre as we know it—not by researching historical accuracy, but by imagining what pirates should be like if they were going to capture a reader’s imagination.

He created Long John Silver, one of literature’s most memorable villains—charming, dangerous, and morally ambiguous in ways that influenced character writing for generations.

And he did it all while dying, coughing up blood in various sanatoriums and tropical islands, writing between bouts of illness that would have stopped most people entirely.

Robert Louis Stevenson proved that you don’t need a long life to leave a lasting legacy.

You just need imagination, determination, and the willingness to write the story you’d want to read—even if you’re too sick to stand, even if nobody thinks you’ll live to finish it, even if you’re just trying to entertain a twelve-year-old stepson on a rainy Scottish afternoon.

He was 32, dying of tuberculosis, when he wrote “Treasure Island.”

He lived to 44—longer than doctors predicted.

And 130 years after his death, children still read about Jim Hawkins and Long John Silver, still dream of treasure maps marked with an X, still imagine themselves sailing on the Hispaniola toward adventure.

The sickly boy who spent his childhood in bed became the man who taught the world how to dream of pirates.

Not bad for someone who wasn’t supposed to survive past thirty.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load