Fifty-Three Minutes That Broke a Lie

A federal courtroom in Honolulu, 1986. A canvas is set on an easel under fluorescent lights that make everyone look a little guilty. A woman sits. A man stands. A judge, tired of words, offers a verdict made of paint: if both claim authorship, both must paint. The jury will watch. The truth will choose its witness.

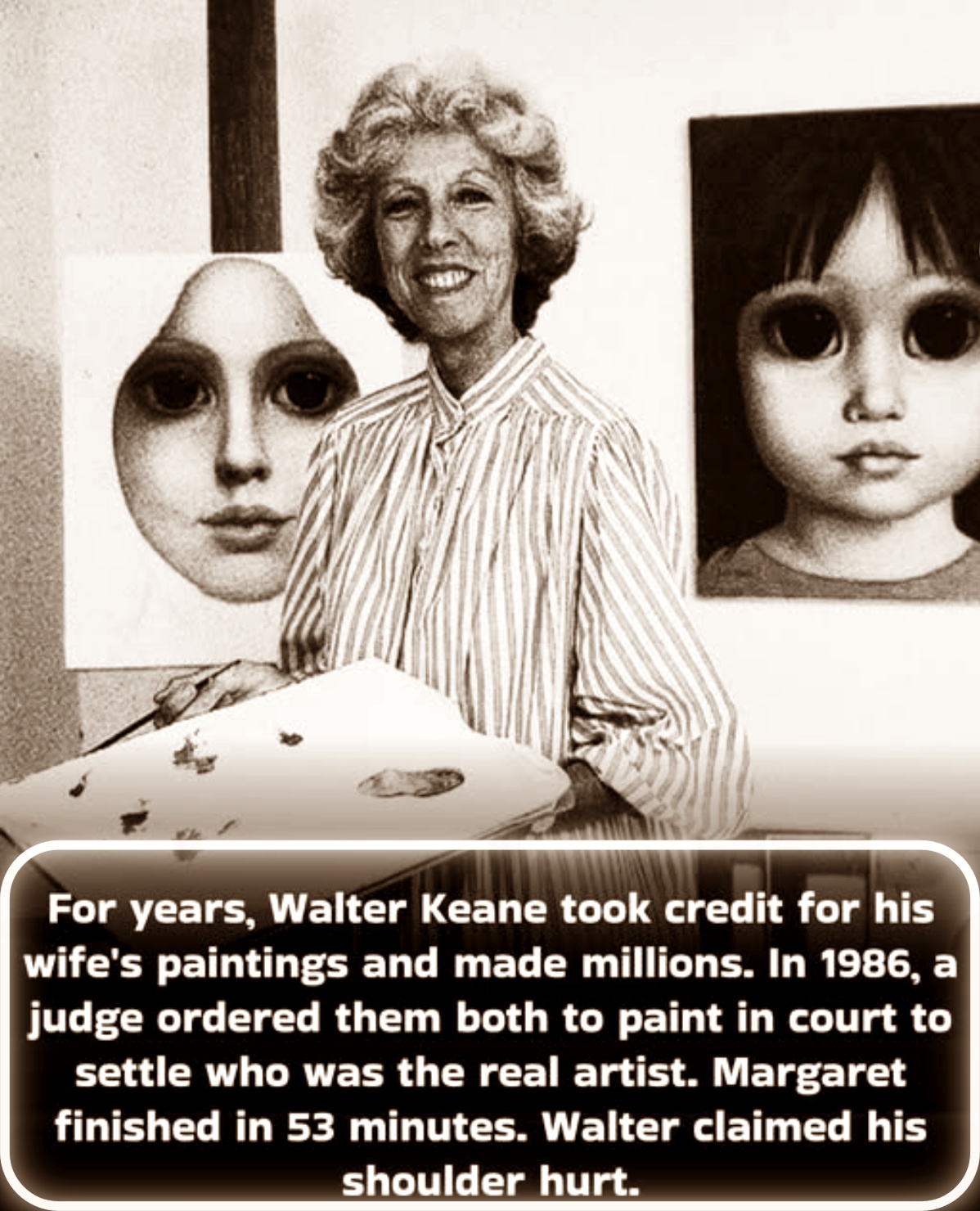

She picks up her brush. Fifty-three minutes later, a haunted child with impossible eyes stares back at a silent room. He, the man who has lived off those eyes, produces nothing. No shape, no shadow, no line. Not even a single tear of paint.

This moment did not come from nowhere. It was assembled across decades of applause and terror—San Francisco patios and basement studios, Hollywood parties and whispered threats, lawsuits and radio confessions. It is the climax of a crime with no fingerprints, a heist pulled not from walls but from a woman’s identity. The gallery shows you the images; the history shows you the theft. Here’s how a signature without a first name became a weapon, how a marriage turned a genius into a ghost, and how a judge turned silence into evidence.

🧭 The Origin Scene: San Francisco, 1955—Charm Meets Talent

The city is a collage of jazz and fog, galleries open to sidewalks like mouths. Margaret is a divorced single mother working as a furniture painter, quiet to the point of invisibility. She has been drawing big-eyed figures since childhood—the gaze that feels like a question. Walter is a real estate agent with a stage presence, fluent in ambition. He tells stories about Paris: ateliers, a café table, a sketchbook stained with rain. He says he studied painting. He has confidence that looks like talent if you don’t check the brush.

They marry. Two people who want a better life invent a partnership: she will make the work; he will bring the world to it. For a moment, the arrangement feels like a rescue.

By 1957, the “Keane” signature appears at outdoor shows. No first names. A surname that invites confusion—and profits. Buyers assume the presence at the booth is the painter. Walter is the presence. He sells. She paints.

When Margaret discovers the deception, she is devastated. He has an explanation that is both cynical and correct: collectors pay more if they think a man made it. Besides, he’s better at selling. He frames the lie as the price of success. The art market nods along without shame.

Margaret agrees to the arrangement, imagining it to be temporary, imagining fairness can be postponed.

🔐 The Hidden Crime: How Authorship Was Taken

This is not forgery. It’s worse. The paintings are real; the theft is metaphysical. Walter becomes the public face of a private labor, the signature that isn’t kneaded by the hand, the biography that absorbs the applause. He hosts parties until they become myth—Hollywood names drifting through rooms where canvases hang like orphaned children: Joan Crawford, Natalie Wood, agents, publicists, reporters. He shakes hands. He makes introductions. He stands in front of a wall and lets everyone assume proximity equals origin.

Meanwhile, Margaret descends into a basement studio. The hours become a form of captivity. Up to sixteen hours a day. Sometimes seven canvases at once. The light is harsh. The silence is not voluntary. Threats become architecture. According to Margaret’s later accounts, he isolates her; he controls the money; he promises violence. If she speaks, he will kill her and their daughters. He hints at mafia connections, a shadow network she cannot verify but cannot risk ignoring. The marriage becomes a ransom note.

And Margaret keeps painting, because in this economy—both emotional and financial—work is the only exit.

🧨 America’s Split Opinion: Critics Hate, The Public Buys

By the early 1960s, the big-eyed children have colonized America. Postcards, prints, posters, coffee mugs—industrial empathy sold at scale. The United Nations hangs them. The Bolshoi Theatre hangs them. Living rooms across the country hang them, a kind of democratized sadness that reads as decoration. Walter’s celebrity blooms. Television segments. Magazine covers. A talent for conversation replaces a missing talent for composition.

Art critics detest the work. John Canaday of The New York Times uses numbers to multiply contempt: a painting with one hundred big-eyed children is “a hundred times worse than an average Keane.” The sentence lands like a gavel in the temple of taste. But the market ignores the critique. Fame and derision build the brand together, a duet that makes Walter’s performance more profitable. You cannot sell sincerity as easily as you can sell spectacle.

The paradox is sharp: the public adores what the elite despises, and the man receiving both adoration and disdain doesn’t make the art. The woman who does is invisible on purpose and under duress.

🚪 Exit, Hawaii: The Separation That Reboots a Life

1964. Margaret finds courage inside a cage. On November 1, she separates from Walter and moves to Hawaii with her daughter. The divorce finalizes in 1965. The Pacific Ocean becomes both distance and balm. She remarries in 1970 to Dan McGuire, a sports writer with a simpler gift: he believes her. Encouragement is the first medicine. He tells her to stop hiding. It sounds easy; it’s not.

That same year, Margaret breaks the spell on a radio show in San Francisco. Live, unscripted, she declares the secret that has been eating her name: she is the painter behind the big-eyed children. Every single one. Walter never painted them. The broadcast is short; the consequence is long.

The revelation detonates across newspapers and living rooms. America loves a scandal; this one is an x-ray of marriage, money, and misogyny. Walter denies everything. He calls Margaret unstable. He claims prior ownership of the aesthetic, pointing to educational toys he designed in the 1940s—big eyes, he argues, were his signature long before her brush. He turns history into a smokescreen and confidence into a weapon.

But Margaret offers the most exact evidence: process. She challenges him to a paint-off at Union Square. Noon. Cameras. Witnesses. Truth crawling out of pigment. Walter agrees, then fails to appear. Margaret paints anyway, and the crowd watches a rumor turn into a technique. The liar is absent. The author is present.

Still, the dispute drags for sixteen years. Interviews. Counter-interviews. Margaret signs her own name on new work in Hawaii, but the shadow of Walter’s claims stalks her like an old debt. Fame, once awarded by a lie, refuses to let go.

📰 The Line That Crossed the Line: USA Today, 1984

In 1984, Walter pushes the narrative into libel. He tells a freelance reporter for USA Today that Margaret is claiming authorship because she believes he is dead—an accusation designed to paint her as opportunistic, ghoulish, cruel. The article is published. Margaret reads it, and something fundamental switches from endurance to offense. Sixteen years of slander have ripened; she is done participating in the fiction of mutual dispute.

She files a federal lawsuit in 1986. Defamation. The case isn’t about taste or style. It’s about fact. Who painted? Who lied? USA Today is included in the suit; the judge dismisses their portion midway through trial. The stage narrows to two characters and an audience of twelve jurors.

Walter, of course, represents himself. He performs with the confidence of someone who thinks charisma is admissible evidence. He makes wild claims. He attacks Margaret’s credibility as if humiliation were a legal strategy. Margaret arrives with canvases and witnesses. Subjects testify: they posed for her, not him. The perimeter of proof tightens around reality.

Then Judge Samuel King instructs a moment so clean it feels cinematic. Both will paint now. Not in principle. Not in a hypothetically fair gallery. In this fluorescent room under oath. Put talent where your mouth is.

Margaret sits and completes “Exhibit 224” in fifty-three minutes. Walter says his shoulder hurts. It will keep hurting forever, it seems, whenever paint is required, wherever cameras exist. His excuse is a familiar friend that only shows up when truth requests a demonstration.

The jury deliberates as if they have been waiting years to do this efficiently. The verdict lands like a bell. Margaret is the true and only artist. Walter slandered her. Damages: four million dollars.

Walter appeals. In 1990, the federal appeals court upholds the defamation verdict but overturns the monetary award on technical grounds. Margaret declines to chase the money. She did not come to court for accounting. She came for her name.

🧬 Psychology and Persistence: Explaining a Long Lie

Walter dies in 2000 at eighty-five, insisting to the end that he is the artist. Court psychologists suggest he may have suffered from a delusional disorder—a condition in which belief divorces evidence but refuses the annulment. It’s possible, then, that Walter believed his own invention even as proof dismantled it. That explanation is neither absolution nor indictment; it is context. It tells us why a man might stand in front of a painting and imagine the brush in his hand. It does not make the paint real.

Meanwhile, Margaret continues. Long after the trial, she paints into her nineties. The children—once melancholic, luminous with sorrow—brighten over the years. The palette warms. The eyes still question, but less like court exhibits and more like invitations. She credits her faith as a Jehovah’s Witness and the steadiness of Dan McGuire for converting trauma into peace. The studio becomes a chapel where labor sanctifies the room.

In 2014, Tim Burton directs “Big Eyes,” reintroducing the story to a nation that had turned scandal into legend. Amy Adams plays Margaret, Christoph Waltz plays Walter. The film collects nominations and, more importantly, attention. A generation that grew up with posters in living rooms learns the provenance they were never told.

Margaret dies in 2022 at ninety-four, having painted decades under her own name, legally and culturally affirmed. The big-eyed children are no longer kitsch in a vacuum. They are artifacts of survival that indict a system as much as they decorate a wall.

🧱 The Architecture of Abuse: How Art Becomes a Cage

Let’s slow the narrative and examine the mechanics. Abuse thrives on plausible deniability and public relations. Walter weaponized gendered assumptions in the art market: the idea that male authorship increases price and prestige. He turned Margaret’s shyness into a tool. He built a social circle that amplified his persona while reducing her to labor. He framed threats as protection—if you say anything, you’ll ruin us, you’ll endanger your children, people won’t believe you, powerful men will hurt us. The basement studio, the long hours, the isolation: all are walls without bricks, walls built from economics and fear.

The “Keane” signature is a masterstroke of erasure. It permits sale while preventing recognition. It scrubs the work of female authorship and lubricates the pipeline of celebrity. When the brand grows large enough, it becomes self-validating. The bigger the audience, the more credible the lie. Margaret’s invisibility is made permanent by her productivity. The more she paints, the more Walter becomes “prolific.”

Crimes of control almost never involve police. They involve silence enforced by threat and profit. The courtroom in 1986 is not just a venue; it’s a rescue device, one that replaces intimidation with procedure.

🧭 The Family Secret: The Name Behind the Name

The story’s most enduring mystery isn’t stylistic. It’s familial. Margaret’s talent was never a rumor in her own house. The secret she kept for two decades was not art theft as an intellectual puzzle. It was a survival mechanism designed to protect her daughters from a man who would weaponize danger. The price of quiet was enormous: her identity, her credit, her legacy, the biography attached to her work.

When she speaks in 1970, she does not simply reclaim authorship. She renegotiates motherhood. The decision to tell the truth is both an artistic announcement and a maternal act. Abuse often forces a woman to weigh honesty against safety; Margaret finally finds a context where truth increases safety instead of eroding it.

In this sense, the “family secret” is the paradox at the center of countless households: hiding the truth to keep the family intact, then telling the truth to save it.

🖼️ The Market’s Blind Eye: Taste, Class, and Gender

Why did this lie last so long? Because markets like neat stories, and patriarchy writes neat stories about male genius and female “assistance.” The art world in mid-century America permitted a flamboyant man to stand in front of a wall and let people assume he made the image. Critics could despise the work and still reinforce the structure by focusing their disdain on “Keane” without asking who “Keane” was.

Buyers bought comfort, not provenance. Prints democratized access but also diluted authorship into a brand. The argument about taste became a smokescreen for an argument about credit. If the paintings are bad, the authorship doesn’t matter. If the paintings sell, the authorship is irrelevant. Both positions erase the worker who produced the object.

Margaret’s radio confession changed the terms. Once the question “Who painted?” entered the public record as a contested fact, the market’s indifference could no longer hide the theft.

⚖️ The Court’s Genius: Turning Art into Evidence

Judge Samuel King’s order wasn’t spectacle. It was jurisprudence that honored the nature of the dispute. Authorship is provable by process in a way that most crimes are not. You can’t reconstruct theft by memory. You can reconstruct authorship by doing the work. The paint-off inside a courtroom is exquisitely fair because it makes performance impossible and labor inevitable.

Fifty-three minutes of watching a hand betray its discipline is more convincing than years of press clippings. “Exhibit 224” isn’t just a painting; it’s a confession of reality. Walter’s sore shoulder is a legend that evaporates under fluorescent light. The jury isn’t judging beauty. They’re judging capacity. Skill in real time becomes truth in real life.

When the verdict arrives, it has more weight than money could give it. It returns a name to a body. It returns a past to a future.

🧠 The Aftermath: When Justice Arrives Without Wealth

The appeals court strips the damages but leaves the truth. Margaret doesn’t pursue the money. She says she just wanted the fact recognized. It’s a sentence that should be hung in every gallery above the title card: recognition is a currency more stable than cash when identity has been embezzled.

The cultural recalibration takes time. The public doesn’t return their prints. They keep loving the eyes. But now the gaze looks back at them with a different sentence under it: you know who made me. The image becomes biography. The kitsch becomes evidence. The living rooms become micro-museums of a woman’s endurance.

Walter’s death seals his narrative; Margaret’s later years open hers. She paints joy, revising the mood without abandoning the gaze. She lives long enough to witness a film turn private pain into public empathy—and long enough to see her name stand alone.

🔍 The Slow-Tight Rhythm: Scenes That Hold and Release

– The outdoor art show: a surname on a corner of canvas, a man smiling at a crowd, a woman at home mixing pigments, unaware that her signature has been swallowed.

– The basement: seven canvases, a clock that seems both too slow and too fast, the air dense with instructions, the door a ritual you don’t open.

– The party: actresses and wine, laughter that sticks to the ceiling, a thousand eyes that nobody asks about; what matters is the theater, not the studio.

– The radio booth: a microphone like a lighthouse; a woman says “I did it” and waits for the ship of belief to find shore.

– Union Square: a missing man; a present brush; public proof without a judge.

– The USA Today line: defamation disguised as a narrative, the straw that becomes a lawsuit.

– The courtroom: fluorescent honesty; a painting timed like a heartbeat; a shoulder injury that appears whenever truth requests company.

– The verdict: a name returns; the money leaves; justice remains.

– The studio after: light less harsh; colors less haunted; faith and marriage converting pain into routine.

These scenes stretch and snap like a wire made of patience, holding the reader in suspension, then releasing them into clarity.

🧭 Why This Story Still Hooks

Because the theft was invisible until it wasn’t. Because a woman’s labor can be exploited in rooms that look like love. Because fame can be built from a lie so frictionless the world calls it branding. Because a judge used the plainness of paint to do what rhetoric could not. Because many readers still live in houses where silence is safer than truth. Because authorship is a kind of citizenship, and Margaret reclaimed hers in public.

The narrative mixes history, crime without handcuffs, and family secrecy in proportions that summon clicks and keep eyes: the scandal of deception, the drama of the courtroom, the slow burn of survival, the reveal that feels inevitable and still lands like shock.

– Authorship is labor, not personality. Protect the hand, not the story.

– Markets will pay for lies when lies sound like confidence.

– Abuse often masquerades as strategy—“This is how we succeed”—until success becomes captivity.

– Silence protects families until it endangers them; the pivot to truth is the moment of rescue.

– Courts can be theaters of fairness when they respect the mechanics of a dispute.

– Recognition outlives compensation when identity has been stolen.

– Popular taste does not absolve exploitation; kitsch can be evidence.

A woman sits in a courtroom, hands steady, brush whispering into canvas. A child’s eyes bloom and accuse—not the jury, not the judge, not the audience, but the decades. Across the room, a man explains why he cannot paint. His shoulder hurts. The story finally refuses him. The painting is logged as “Exhibit 224,” but the label is too small for the moment.

The verdict gives back what the parties took: her name. The prints in a million homes don’t change; the truth beneath them does. When you look at those eyes now, you are not looking at a brand or a rumor. You are looking at Margaret Keane, who survived a marriage that made her a machine, who told a secret that lifted a roof, who painted herself free in fifty-three minutes under fluorescent lights. The crime is clear. The history is written. The family secret is no longer a secret. The gaze is hers—and finally, the world knows it.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load