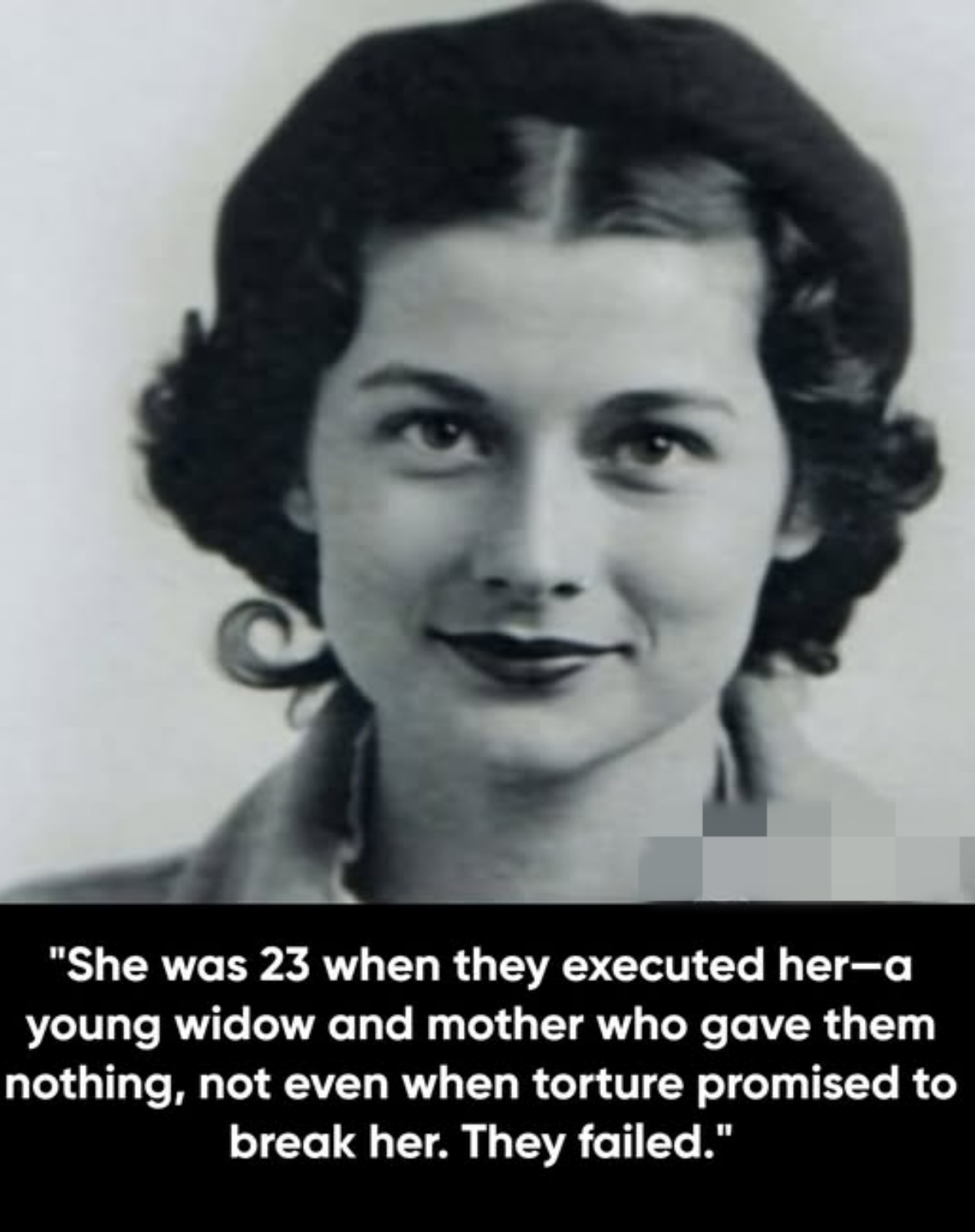

She was 23 when they executed her—a young widow and mother who gave them nothing, not even when torture promised to break her. They failed.

This is Violette Szabo. And her courage still echoes.

Born in 1921 to a British father and French mother, Violette grew up moving effortlessly between two languages, two cultures, two worlds. Those who knew her as a child said there was something extraordinary about her—a fierce loyalty, a quiet fire that burned steady.

At 19, she fell in love with Étienne Szabo, a handsome French Foreign Legion officer. They married quickly, the way people do when war makes every tomorrow uncertain.

A year later, in 1942, she gave birth to their daughter, Tania.

And then the telegram arrived.

Étienne had been killed at El Alamein in October 1942, fighting Rommel’s forces in the North African desert.

Violette was a widow at 21. Left with a baby daughter and a grief deep enough to drown in.

Instead, that grief forged her into something unbreakable.

She could have retreated into mourning. Could have focused solely on raising Tania. Could have chosen safety.

Violette chose war.

She joined Britain’s Special Operations Executive—the covert organization that dropped agents behind enemy lines to sabotage Nazi operations and support resistance movements. The SOE didn’t recruit ordinary people. They recruited ghosts who could disappear into occupied territory and fight in the shadows.

The training was brutal. Parachute jumps into darkness. Weapons expertise. Hand-to-hand combat. Interrogation resistance techniques designed to prepare agents for capture and torture.

Violette excelled at all of it.

In April 1944, just weeks before D-Day, she parachuted into Nazi-occupied France under cover of night. Her mission: coordinate with the French Resistance, gather critical intelligence, and disrupt German communications ahead of the Allied invasion.

She moved through occupied territory with nerves of steel and perfect French that made her invisible. She organized sabotage operations that would help pave the way for liberation. She was 22 years old, operating alone in enemy territory, with a baby daughter waiting at home.

Her first mission was successful. She returned to England. She could have stopped there.

In June 1944, she volunteered for a second mission.

Everything went wrong.

Near the village of Salon-la-Tour, Violette and her Resistance colleagues ran into a German roadblock. SS troops opened fire. The situation was hopeless.

Violette could have run. Could have tried to save herself.

Instead, she stayed behind.

She took up position and provided covering fire—giving her French comrades the seconds they needed to escape. She fought trained SS soldiers with nothing but a Sten gun, determination, and absolute refusal to abandon her team.

She fought until her ammunition ran out. Until there was nothing left but her own body between the enemy and the people she’d come to save.

They captured her. Beaten. Bloodied. Defiant.

They tortured her. Demanded names. Locations. Codes. Details about resistance networks and SOE operations.

Violette Szabo gave them nothing.

Not one name. Not one location. Not one shred of intelligence that could endanger the people she’d fought beside.

They sent her to Ravensbrück concentration camp—the Nazi hell designed specifically for women.

For months, she endured unspeakable cruelty. Starvation. Beatings. Psychological torture designed to break even the strongest spirits.

Other prisoners remembered her. They recalled how she never stopped encouraging others. How she found small ways to resist. How her spirit remained unbroken even when her body was failing.

In late January or early February 1945, the Nazis executed Violette Szabo. She was 23 years old.

Just weeks later, in April 1945, Allied forces liberated Ravensbrück.

Weeks. She was murdered weeks before freedom arrived.

But here’s what the Nazis could never kill:

The intelligence she protected saved countless lives.

The resistance networks she refused to betray continued fighting until liberation.

The daughter she left behind—Tania—grew up knowing her mother died a hero, not a victim.

Before Violette left for France that final time, her SOE handler Leo Marks gave her a poem to use as her cipher code—a way to encrypt messages. The poem became forever linked to her story:

“The life that I have is all that I have,

And the life that I have is yours.

The love that I have of the life that I have

Is yours and yours and yours.”

Those words weren’t just code. They were prophecy.

Violette Szabo gave everything—her safety, her future, her chance to watch her daughter grow up, her very life—because she loved something more than her own survival.

She loved freedom. She loved the people fighting for it. She loved the idea that her daughter might grow up in a world without tyranny.

After the war, Britain posthumously awarded her the George Cross—the nation’s highest civilian honor for gallantry. Her medal sits in the Imperial War Museum. Her name is carved on the SOE memorial in Valençay, France, alongside other agents who never came home.

But her real legacy isn’t in museums or monuments.

It’s in the example she set: that courage isn’t the absence of fear—it’s loving something more than you fear death.

Violette Szabo was 23 years old. A young widow. A mother who would never see her daughter again. A woman who had already endured more loss than most people face in a lifetime.

She could have chosen safety. She chose resistance.

She could have broken under torture. She stayed silent.

She could have saved herself. She saved others instead.

At 23, she had already lived more courageously than most people do in eight decades.

Her daughter Tania grew up without a mother. But she grew up free. And she grew up knowing that her mother was the reason countless others got to grow up free too.

We owe Violette Szabo something simple but profound: we owe her the act of remembering.

Remembering that freedom isn’t free. That someone always pays the price. That a 23-year-old mother chose to pay it so others wouldn’t have to.

Her name was Violette Szabo. She was a daughter, a wife, a mother, a warrior, and a hero.

And even in death, they couldn’t break what she protected.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load