It was a crisp Los Angeles evening when Sarah Paulson walked onto the sound-stage that would soon be transformed into the house of the Borden family — the one immortalized by history and legend for the brutal 1892 axe murders of Andrew and Abby Borden. Cameras rolled. Crew bustled. But in Paulson’s eyes, there was something different this time: a quiet thrill, and a hint of danger.

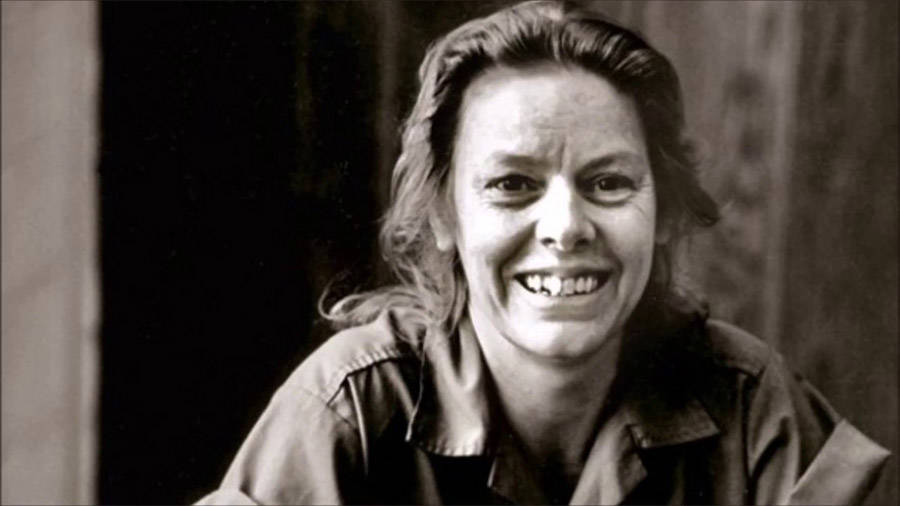

Paulson was about to embark on what might be the most audacious role of her career — namely, portraying Aileen Wuornos, the convicted Florida serial killer executed in 2002. Yes: Wuornos. And yes: the show is called Monster. But the curious part? Wuornos isn’t the headliner of Season 4. She is, instead, a shadow figure, stalking the edges of a narrative centered on Lizzie Borden, the infamous axe-murder accused women’s icon of 19th century America. Producers say the pairing is intentional: a thematic bridge between women killers separated by more than a century.

The news broke quietly. Variety reported Paulson was “in final talks” to play Wuornos. The official cast list already named Ella Beatty as Lizzie Borden, Charlie Hunnam as Andrew Jackson Borden, and Rebecca Hall as Abby Borden. Netflix offered no comment. Insiders say Paulson, famously loyal to Murphy’s “Murphyverse,” viewed this as her next major notch, a chance to collapse genre, history, and character into one elegant, horrifying package.

Why it matters.

Paulson has built a career on playing troubled, dark, morally complex women: from Marcia Clark in The People v. O. J. Simpson to multiple characters in American Horror Story. But Wuornos is on another plane. In the 2003 film Monster, Charlize Theron won an Oscar for her portrayal of Wuornos — and with good reason. Wuornos wasn’t just a killer; she was a cultural lightning rod: sex worker, lesbian, violent, abandoned by society, executed by the state. Portraying her is a risk: an actor can be lauded, or condemned.

According to an early dossier, Season 4 of Monster won’t simply retread Wuornos’s story. Instead, it will examine the complex ripple effects of Borden’s case and how female killers have been mythologized. Sources say Paulson’s character may appear in flash-forwards or narrative bookends, drawing modern connections to Borden’s legacy. The show aims to ask: what happens when society makes monsters of women? How much of the fear is real — and how much is invented?

The behind-the-scenes buzz.

Crew members on the Los Angeles production say the tone has already shifted. Instead of stylised horror, there’s heavy historical research going on. Paulson arrived with a stack of Wuornos transcripts, letters, court records. She’s studying not only Wuornos’s voice but her posture, her pauses, her pain.

One source described a wardrobe fitting where Paulson sat silently in a basic white tank-top, circling the room, letting costume assistants stare at her. When asked if she wanted makeup, she said: “Make me invisible. Let the truth be what you see.” This echoes her past approach, but here the stakes feel higher.

Murphy, the producer, met Paulson privately. “I want you haunted,” he told her. “Not by Frankenstein’s monster. By the monster they made you to be.” That phrase has already joined industry legend.

The controversy brewing.

But not everyone is thrilled. Online forums light up with criticism. Some fans of Theron’s Monster argue Paulson is stepping into a role with too much baggage. Others wonder whether linking Wuornos and Borden — very different women in very different eras — will feel forced, or worse, exploitative. Reddit threads point out that Wuornos has already been portrayed multiple times; is the retelling necessary? Some say the “true-crime whitening” of female violence is becoming a trend.

Behind closed doors, producers are aware of the minefield. Netflix’s recent history with controversial true-crime stories means the KPIs aren’t just about ratings — they are about backlash, ethics, and representation. Inside sources say there have been “content warnings” and “sensitivity briefings” on set. Paulson’s camp insists this is not sensationalism — it’s interrogation.

What this means for Paulson.

For an actress of her calibre and longevity, taking on Wuornos is both bold and strategic. Paulson knows her way around genre and prestige. But she also knows the danger of being typecast as the “dark woman actor.” She’s been there: when studios muttered “too serious,” “too weird,” “too scary,” she smiled and won. This move feels like her defiant one-last-move: I’ll do what frightens you.

Privately, friends say she’s prepping differently. She’s isolated herself for weeks, refused dinner parties, and insisted on immersive sessions with survivors of sexual violence and fallen criminal justice system workers. She calls this preparation her “moral compass.”

What about the story?

We’re told Season 4 opens with the Borden murders of 1892. The series then jumps forward through decades, as historians and interrogators examine how Borden’s case became a template for female-violence hysteria. Wuornos emerges in the 1980s–90s segment as a grim reflection of Borden’s legacy — different in motive, method, and era, but tethered by the same cultural spotlight: the woman-killer.

This structure allows the show to explore not just the crimes, but media, gender bias, trauma, and the criminal justice system’s treatment of female offenders. It’s ambitious. It’s messy. But Paulson evidently signed on because she wants messy.

Why now?

With true-crime saturation, audiences might be jaded. But the angle is shifting: viewers no longer just want violence — they want context, commentary, and conscience. Paulson’s involvement raises hopes that this won’t be another “glamorised killer” show. She has a reputation for depth. The series’ backward linking of two killers separated by nearly a century suggests the producers aim for something beyond gore.

The risk.

Of course, risk is everywhere. Portraying Wuornos means walking a line between empathy and glamorisation. Network executives are reportedly nervous. One early draft of Episode 5 ended with a dramatized shot of a victim’s ghost drifting behind police lights — too much, says Netflix. They pulled it. The producers reworked it to focus more on survivors.

The season is currently filming in Los Angeles — locations doubling as Fall River, Massachusetts (for Borden) and Florida. Paulson is on set, her presence commanding but quiet. She’s been spotted shifting between wardrobes: a corseted 1890s gown one day, a ragged denim outfit for Wuornos the next.

What insiders whisper.

One unnamed costume assistant told us: “If Sarah walks past you in full makeup as Aileen, you’ll think she’s real. I almost screamed.” Another crew member mentioned Paulson’s intense gaze during a rehearsal: “She didn’t blink. Not once.”

Industry reaction.

Agents are already calling this “the next big role” for Paulson. Casting directors whisper that playing Wuornos could catapult her into the Oscar conversation again. But critics caution: if it misfires, the backlash will be brutal. A misstep here isn’t just a bad review — in true-crime circles, it could look like commodification of trauma.

Why viewers should care.

Because we live in a culture obsessed with violence, yet terrified of female agency. The Monster series has previously covered the Menendez brothers, Jeffrey Dahmer, Ed Gein. Usually men. Now the tables turn. Two women. Two killers. Two eras. A chance to ask: what changes? What stays the same? And how much of the horror is behind bars — and how much is in the gaze?

Final thoughts

As Sarah Paulson leaves the set each day, walking past the 19th-century manor doors and into a dressing trailer where Wuornos’ prison jumpsuit waits, she carries more than a script. She carries decades of storytelling, of industry reinvention, of women performing violence to be seen as equals. She carries the gamble of whether true-crime can still surprise us — or whether it’s just another echo chamber.

When the camera finally rolls, she’ll face not just a character, but a legacy. She’ll confront the monster we made of her, and the monsters we ignored. The only question now: Will she show us what happens when we stop making monsters — and start making sense?

“In a world built to fear the female body, the female voice, the female crime — maybe the real monster was our silence all along.”

This season isn’t just about one killer. It’s about us.

And yes — it might just be the most talked-about television event of the year.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load