Three hikers found a forgotten fire lookout that wasn’t on any map. At the top: a seated set of human remains, a rusted rifle, and a notebook with final words. A chilling true story of how the mountains keep secrets — and return them after more than half a century.

September 2019, deep in Montana’s Flathead National Forest, three friends pushed through dense timber to camp in true solitude. They didn’t expect to meet a ghost of the past: a wooden fire lookout, weathered to silver-gray, its dark windows like a skull’s eye sockets. It wasn’t on any modern map. Curiosity pulled them up the creaking stairs, and on the top floor they found the ending to a 62-year-old cold case: David Miller — the hunter who walked into the mountains in October 1957 and never came home.

If generational mysteries captivate you, stay to the end. This isn’t just the journey of a skilled outdoorsman; it’s a warning about survival, desperation, and the unforgiving indifference of the wild.

– The man built by mountains:

Fall 1957, David Miller, 34 — tall, lean, blue-eyed, a man who could read terrain the way others read books. He’d served with the First Infantry Division, landed on Omaha Beach on D-Day, fought through France and Belgium, and witnessed the liberation of camps in Germany. After the war, he settled in Cascade, Montana, worked as a forest ranger, and lived with his wife Helen (an elementary school teacher) and their children: Tommy (8) and Lisa (5). A model family, trusted neighbors — the fabric of an 800-person town.

– The fateful hunting day:

Pre-dawn, October 15, 1957, David checked his gear: Winchester Model 70, hunting knife, compass, waterproof matches, first aid kit, canteen, rope, tarp — everything a careful man carries. He kissed Helen’s forehead: “Back by seven at the latest.” At 6:15 a.m., he fueled up at Morrison’s, chatted about weather, grabbed a Coke and a candy bar, then drove into the mountains via Highway 89 and Forest Road 486.

– No return:

7:00 p.m. passed, then 7:30, then 9:00. Helen called Sheriff Tom Bradley. At first light, Bradley traced David’s route. They found his 1955 Ford F-100 — green, with the Forest Service emblem — parked at the trailhead. Doors locked. Pack, canteen, lunchbox inside. Rifle missing — David had taken it. Three signal shots cracked the morning. The forest answered with silence.

– Searching the void:

For three weeks, over 50 people — rangers, volunteers, bloodhounds — grid-searched valleys, ridgelines, drainages, cliffs. The dogs picked up scent near the truck, then lost it within half a mile. No footprints, no spent casings, no blood. Grizzly attack? Sudden medical collapse? Suicide? There was no evidence for any theory, and the community, especially the family, rejected the darkest whispers. November brought heavy snow; the search halted. The spring of 1958 brought renewed effort — still nothing.

– A cold file and a lifetime of waiting:

In 1964, David was declared legally deceased so the family could receive benefits. Helen never believed he had “vanished.” She kept his clothes in the closet, his coffee mug on the shelf, his boots by the back door. Every October 15th, she drove to the trailhead, looked into the mountains, and asked questions without answers. Her last visit was 2010 — 53 years to the day. In 2015, Helen died, laid to rest beside a headstone that read “Lost but never forgotten” — over an empty grave.

– The forgotten fire tower:

Hundreds of fire lookouts were built across America in the 1920s–1950s. By the 1970s, planes, satellites, and improved radios made most obsolete. Tower Lookout 7 in Flathead was abandoned in 1971, about three miles as the crow flies from David’s trailhead — nearly six miles of brutal, off-trail terrain. Unmarked, unmapped by modern GPS, hidden by regrown forest.

– Three hikers collide with history:

September 12, 2019, Jake (software engineer), Amy (physician assistant), and Marcus (biology teacher) left Missoula to hike off-trail for true solitude. Through the trees, they noticed something geometric: a 70-foot fire tower, silver-gray wood, broken stairs, a canted cabin. “It’s not on any map,” Jake said. They hesitated — then climbed, one careful step at a time, as the tower groaned.

– The room at the top:

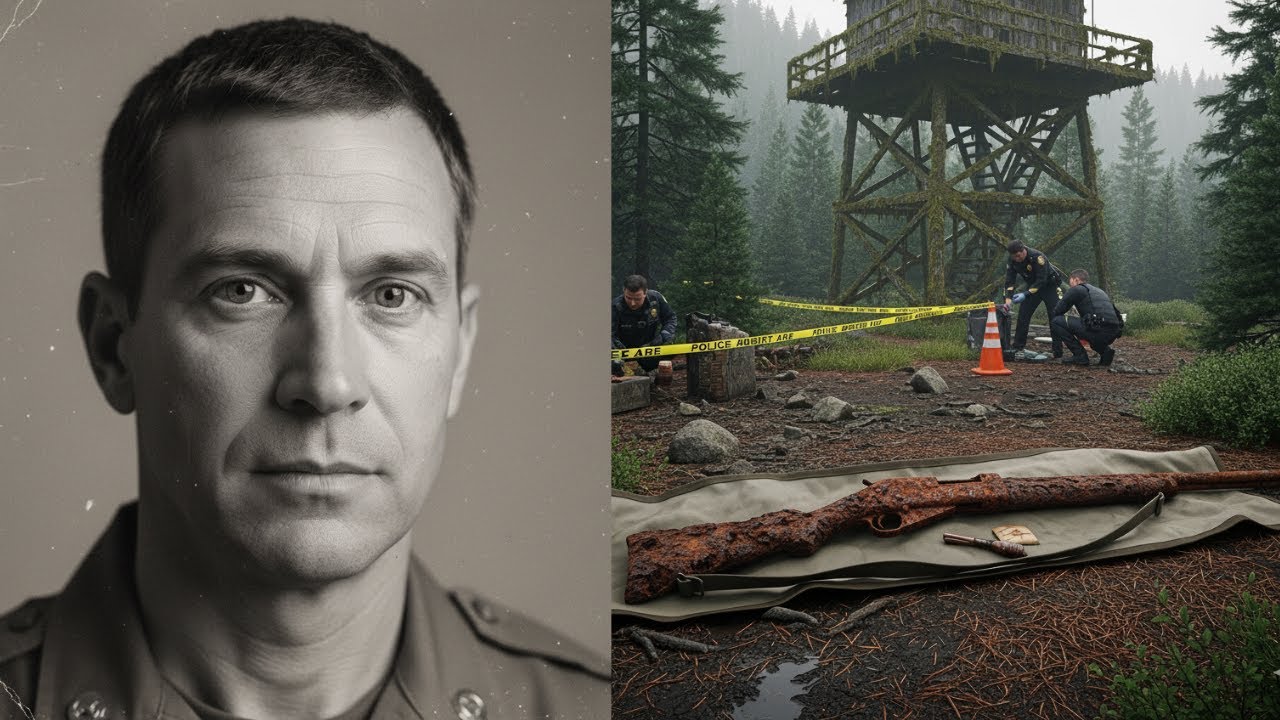

The door hung by a single hinge. Inside: a warped table, a toppled chair, windows cracked to spiderwebs. In the corner beneath the eastern window, a body seated against the wall: leather hunting boots still laced, tattered canvas pants, a brown-and-tan camo jacket in shreds, skeletal hands clutching a small notebook. Beside him: a rusted Winchester. The skull tilted back, jaw open, facing the forest — as if the last view was the world below.

No cell signal. Jake photographed carefully, marked GPS, and they hiked out fast to call authorities.

– Recovery and forensics:

A combined team — forensics, rangers, a structural engineer — reached the site September 14th. The tower was too dangerous to support multiple people; they documented everything and planned a controlled collapse after removing remains. Near the body: a leather wallet, a compass, hunting knife, waterproof match tin. In the wallet: a Montana driver’s license, photo faded but name clear — David A. Miller, Pine Street, Cascade, issued 1956. A veteran ranger blanched: “David Miller — the one who vanished in ’57.” The rifle was a Winchester Model 70, matching David’s. The notebook was fragile, but possibly recoverable. On the floorboards, knife-scratched marks — most worn smooth, one still legible: “October 17.”

The remains were transported to Missoula. The tower was brought down safely. Among the debris: shell casings, cloth fragments, a wristwatch stopped at 3:47.

– Last words from ruined pages:

Dental records confirmed the identity: David Miller. Cause of death, after so long, pointed to hypothermia, compounded by a likely ankle fracture and dehydration. Specialists painstakingly restored parts of the notebook using imaging. The entries spanned October 15–19, 1957 — five days. They were devastating:

+ Oct 15 (morning): David tracked a large buck uphill, leaving his planned route. He spotted the fire tower a quarter mile away and climbed to use the wall map to reorient. On his way out, he stepped on a rotten floorboard. His leg plunged through to the knee. He wrenched his ankle — badly twisted, possibly broken.

+ Oct 15 (evening): “Can’t bear weight. Tried stairs.” The exterior spiral stairs demanded sure footing; with one leg compromised, he nearly fell. The structure swayed. He retreated to the cabin: safer than risking a 70-foot fall.

+ Oct 16: “Fired three shots this morning. Hope they hear.” He noted voices and truck sounds in the valley. The rifle’s echo bounced strangely. Searchers likely assumed it was another hunter.

+ Oct 17: “Can see them searching. Too far to shout. Rifle almost empty. So cold.” The day carved into the floorboards. He could see them — and they could not see him.

+ Oct 18: “Ankle black. Can’t feel toes. Used last bullets. Nobody coming. Tell Helen I’m sorry.”

+ Oct 19: Final, trembling lines: “So cold. Love you, Helen. Love you, Tommy Lisa. Very sorry.”

– The cruel calculus:

David endured four to five days after injury. October nights in Montana’s high country drop below freezing. He had dressed for day hunting, not overnight exposure. A single canteen and a packed lunch would last one to two days. Without resupply, dehydration compounded cold, pain, and exhaustion. He died watching searchers sweep the wrong valleys — a few miles away, out of voice range, out of sight lines. For 62 years, his body slowly mummified in the dry alpine air, three miles from the trailhead — just beyond the searchers’ intuition.

– The funeral and what changed:

November 1, 2019, Cascade buried David Miller at last. Tommy (70) and Lisa (67) stood before their father’s coffin, near their mother’s grave, and said goodbye. “The mountains don’t care about experience,” Tommy said. “Dad fought to live. He tried to signal. He didn’t give up. He just ran out of time.” Montana updated search-and-rescue protocols: abandoned fire lookouts are now routinely checked; a database of GPS coordinates for historical structures — even those erased from modern maps — is standard issue. David’s restored Winchester, wallet, and notebook are displayed at the Montana Historical Society Museum in Helena under “The Hunter Who Couldn’t Come Home.”

The ridge where the tower stood is now Miller’s Ridge — a map label to remind anyone passing that a man once watched hope move below him, then faded in silence.

The moment that stuns isn’t the skeleton — it’s the recovered notebook, especially October 17: “Can see them searching.” David was right there, a mile or two away — close enough to see figures, too far to carry a voice. He fired until he had no bullets. He carved the date into the floor — a time-stamp for those who would come later, proof he saw rescue, believed, waited.

The most painful twist: he wasn’t lost in chaos. He climbed the tower to orient, stepped onto a single rotten plank — a small error, an aging board, becoming a sentence. The staircase demanded two good legs; he had one. Staying aloft was the safer choice — until safety turned into a trap. High above the searchers, directly “over” the sweep zones, he froze, dehydrated, and dwindled — eyes set on where people were.

David Miller’s story spans 62 years and still feels unfinished. It leaves:

– For the family: an answer, late but real — that he fought, thought of his wife and children, and wrote to them at the end.

– For the community: a hard lesson in search geometry — modern maps aren’t gospel; forgotten structures can be the key.

– For rescuers: new protocols, better data, and a habit of asking, “What did the map erase?”

Visitors in Helena pause before the rusted Winchester and the faded notebook. They don’t just see a solved case; they see the fragility of small decisions: one misstep, one rotten board, one staircase built by time.

Up on Miller’s Ridge, mountain wind skims the place where the tower is gone. No cabin. No stairs. Just a name on the map — a marker to remind anyone entering the backcountry that wilderness is indifferent and exacting. It doesn’t care if you survived D-Day or just bought your first boots; it demands respect, preparation, and, when lost, a willingness to search the places people — and maps — forgot.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load