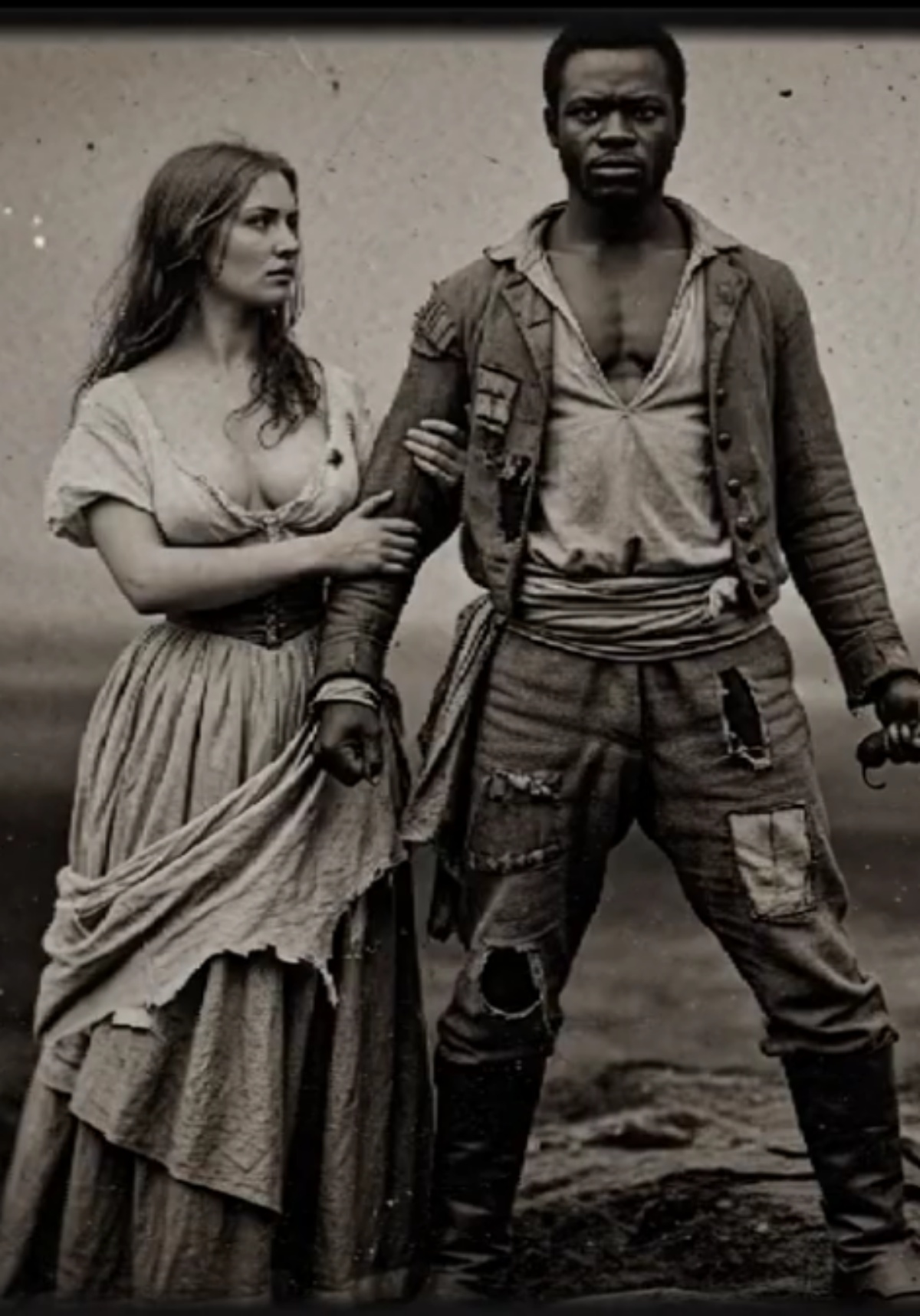

A slave uprising. A master dead. A daughter complicit. A plantation wiped from every record—until the papers resurfaced.

Clark County, Mississippi, 1856. A name disappears, and with it 300 acres of cotton, a two-story house, 47 enslaved souls, and the man who commanded them. Not burned, not sold, not foreclosed—erased. County ledgers show a blank space. Census enumerators step around it like a hole in the earth. When federal marshals arrive months later, they find ash, silence, and a story no one dared write down.

This is the case of Thornwood Plantation: a place that flickers in and out of the archive like a ghost. A place where a literate field hand—call him Ezekiel—watched, waited, learned the system’s pulse, then struck it where it was weakest: the paper. What follows is not the myth that survived in whispers, but the version stitched from ledger entries, forged wills, sealed journals, and the softest confession a South too proud to listen ever received.

Let’s unpack the plot, the forged documents, the love story that violated a nation’s most guarded line—and the archive that proves it almost happened too cleanly to believe.

I. Ground Zero: Black Earth, Red Dirt, White Timber

Thornwood sat three miles east of Quitman, a straight-backed house fronted by a porch that sagged on the east corner. Fifty yards behind: a separate kitchen house. One hundred yards beyond that: two rows of twelve cabins, positioned so the master could measure human lives from his bedroom window. Cotton ruled here—the kind that grows shoulder high and bleeds fingers raw.

– The owner: Marcus Thornwood, 48 when our story begins, heir to debt and desperation. Not rich enough to be generous, not poor enough to be humble.

– The heir: Catherine, educated at the Madison Female Academy—literature, French, mathematics—and, dangerously, philosophy. She learned Locke and Jefferson in classrooms where “liberty” wore lace.

– The labor: 47 enslaved people, their names scattered across bills of sale, whipped into the ledgers as “assets,” then disappeared.

The plantation’s topsoil is as black as rumor, the road as red as dried blood after rain. The place is designed for harvest and hierarchy: a machine powered by human pain and reinforced by paper.

II. The Defect in the System: A Literate Slave

The bill of sale calls him “Ezekiel.” Age 24. Strong build. Field hand. Literate.

That last word should have warned everyone. Literacy is not a trait in bondage; it’s an aperture. It admits newspapers, abolitionist pamphlets, maps. It creates a private interior where orders don’t echo. It teaches two things at once: that the world is larger than a plantation, and that plantations can be edited.

– Taught in secret by a sickly master’s son on another estate.

– Perfected in silence: eyes lowered, dialect performed on command, mind racing while hands harvest.

– Five years observing Thornwood: Marcus’s debts to Mobile brokers, his study habits, his whiskey, his keys, his fear.

Where most saw a field, Ezekiel mapped a system: work rotations, gate timings, infirmary routines, overseer patterns, freight schedules. He learned what it takes to move cotton, then imagined moving something bigger: status.

III. The Promotion that Doomed the Master

October 1853, a “catastrophic efficiency” moment. The overseer—Briggs—gets caught skimming cotton. Marcus fires him and makes a decision born of arrogance and thrift: he elevates Ezekiel to overseer.

It’s the oldest management mistake in the book: confusing obedience with loyalty, competence with consent. For Marcus, it solves payroll. For Ezekiel, it opens everything.

– Access: storerooms, pass-books, schedules, Marcus’s desk.

– Authority: assigning work details, moving people without suspicion, opening the study for “accounts.”

– Opportunity: copying maps, memorizing creditor chains, teaching in darkness.

By day, the fields hum. By night, lessons begin: letters in dirt, figures on bark, newspaper fragments smuggled from the master’s desk. The enslaved are sorted into cells of five—each person with a role, each group with a code. The vocabulary expands: quota, ledger, lien, manumission. So does ambition: escape is redefined as overthrow.

IV. The Daughter’s First Betrayal (Of Herself)

Catherine had learned to compartmentalize: sunlight for the parlor, darkness for the quarters. That changes when she hears a sound she can’t file away: the low, rhythmic murmur of voices learning.

She discovers Ezekiel teaching. She should report it. Instead, she listens, then returns with contraband: a primer, a copy of the Constitution, and a map north. It’s not absolution; it’s a step. Her guilt doesn’t dissolve; it acquires a direction.

– She meets Ezekiel’s gaze for a full second. A conversation in silence: I know. I know you know. Are you going to stop me? I don’t think so.

– She begins to watch—not the plantation of her childhood, but a system undergoing reprogramming.

When a neighboring girl named Mary is dragged past town, barefoot and bleeding, and whipped publicly as example, Catherine’s rationalizations snap. The world she’s inherited requires the destruction of children. She picks a side.

V. The Paper Coup: Liberation by Signature

December brings federal whispers. A marshal named Garrett visits, a local magistrate in tow, murmuring “Fugitive Slave Law” and “illegal education.” Three days hence: a full search. Marcus blusters; Catherine understands the math. Somebody talked. If the search lands, they all hang.

Ezekiel does what good generals do under pressure: he accelerates the plan.

– Phase 1: Neutralize Marcus. Not with a gunshot in the yard—too loud—but with a pillow and a partner. Catherine kills not a father, but a king. Ezekiel pins the arms; the entire plantation’s gravity shifts.

– Phase 2: Forge the future. A will—dated weeks back—leaving Thornwood to Catherine, outlining gradual emancipation and wage labor. Letters to a banker about “Christian conscience.” Diary entries describing a moral awakening. All plausible because white men love believing they freely chose what justice demands.

– Phase 3: Create a scapegoat: Ezekiel “dies” in a staged attack; Catherine “shoots” him in self-defense. They bury a decoy. The story is ugly but familiar—the kind whites nod along to without fact-checking.

A doctor signs a death certificate for Marcus: heart failure. The county files the will. The paper machine that enslaved 47 people is repurposed to slow its own teeth.

VI. Seven Months of a Different World

Public face: a plantation under a bereaved daughter, implementing a gradualist plan that offends the hardliners and flatters the moderates.

Private reality: a collective. Labor reorganized by consent; profits shared; a fund to buy relatives out of hell. Ezekiel—resurrected as “Joseph,” an overseer from Virginia—runs logistics from the shadows. Catherine handles neighbors, creditors, and the morality play called “appearances.”

– Productivity rises. It turns out that people who won’t be whipped work faster and smarter.

– Children learn to read without a lookout posted at the door.

– Whips collect dust.

The operating thesis becomes a threat: If Thornwood thrives without chains, how many chains are lies?

VII. Enemies Assemble: Debt, Law, and Pride

Success triggers its own alarm.

– Dalton, the Mobile creditor, visits. He admires the ledgers and threatens foreclosure in the same breath. “One missed payment and we move.” Catherine bores him with solvency.

– Sheriff Cobb arrives, all hat and suspicion. He wants to interrogate “the property.” Catherine permits supervised interviews. The workers perform the parts they wrote themselves: grateful, gradual, guileless. Ruth, an elder with steel under her shawl, points him to Ezekiel’s “grave.” Cobb stares at the cross and decides not to dig. For now.

The South is full of men who know how to wield violence; fewer understand paperwork. That asymmetry buys Thornwood time.

VIII. The Line You Don’t Cross—And They Cross It

August brings storms and a secret that could lynch an entire idea. Catherine and Ezekiel—partners in treason—become lovers.

We will not make this a romance that saves a country. It saved no one. It didn’t need to. It was the quietest and loudest defiance: a white woman and a Black man choosing each other in a world calibrated to kill that choice first.

– Ruth sees and says only, “Lord help you both.” It’s not blessing or curse. It’s weather report.

– Their love doesn’t slow the plan; it clarifies the stakes. If they’re caught now, the charges won’t be fraud or conspiracy. They’ll be “miscegenation,” the legal word that condenses every southern anxiety into fire.

The danger spikes. The work continues.

IX. The Fugitive at the Gate

Mid-September, a boy named Jacob arrives at midnight—whipped nearly to death for learning letters. To harbor him is to invite federal law into the parlor. To refuse him is to betray the very grammar of Thornwood’s revolution.

They take him in. Slave catchers follow. Dogs sniff. Deputies curse. Jacob slips through the woods with Ruth and “Joseph” guiding him to the next station of a network that everyone denies exists. Sheriff Cobb adds a tab to the bill he intends to collect later.

X. The Spy Next Door

Sutherland, a planter with a theology of hierarchy and a taste for other people’s business, has been watching. The happy laborers bother him. The yields bother him. The idea of a functioning wage-labor plantation bothers him most of all. He sets a simple trap: he bribes for gossip and takes to the woods at night.

One evening he sees what he came for through a lit window: Catherine and Ezekiel together. That image gives the South everything it needs to justify anything.

– Sutherland gallops to town. Sheriff Cobb smiles thinly. Warrants are drafted for harboring a fugitive, fraud, conspiracy—and the paragraph that guarantees the noose: interracial relations.

– They schedule the arrest two days out. Cobb wants the gallows to be busy and public.

A deputy named Fletcher, not yet rotten, warns Catherine at midnight. “Forty-eight hours. They know about you both. Run.”

XI. The Vote

Revolution is easy to romanticize and hard to organize. Catherine and Ezekiel call everyone into the largest cabin. No speeches, just a choice.

– Option 1: Stay. Claim coercion. Say you were misled by a “mad” overseer and a weak mistress. The script will be believed because the audience wants to believe it. You will become slaves again. You will live.

– Option 2: Run west to Mexico. It’s a thousand miles of lawmen and men who think they are the law. Some of you will die. Those who survive will be free.

It’s not unanimous. Twelve choose to stay. Thirty-five choose the road. Both choices are courageous. Both are tragic.

XII. Ashes as Strategy

They pack: food, tools, forged papers, silver hammered into circles, gold that belonged to a man they smothered. Ezekiel works through the night writing identities that might survive a glance: freed men with trades, servants in transit, field hands bound for contracts.

They break into small parties. The rendezvous is Texas. The route is everything but obvious.

Before dawn, Catherine and Ezekiel light the fuse on memory. They burn the main house first; the separate kitchen next; the overseer’s cottage last. Ezekiel retrieves a leather-wrapped journal and seals it in oilcloth. The flames swallow the study that taught him how to answer back.

When Sheriff Cobb arrives that afternoon, Thornwood is smoke and stories. The twelve who remained perform their lines: Ezekiel went mad, attacked Miss Catherine, set fires; the slaves panicked and fled. Cobb digs up Ezekiel’s grave. Burlap and stones. He stares into the hole and sees only his own reflection.

XIII. The Thousand-Mile Sentence

Mexico is farther away in fear than on any map. The journey takes four months.

– They travel by riverboat with forged bills of sale that certify freedom no one believes and everyone accepts for a bribe.

– They move through pine and scrub, crossing where sheriffs don’t bother to patrol, where Rangers do and think bullets settle paperwork.

– Five die: fever, snake, gunfire. Thirty make it to the Rio Grande. The water is shallow this winter; the law is not. They cross anyway.

On the southern bank, American law stops pretending to own them. The breath everyone has been holding collapses into a single exhale.

They land in a town where names can be softened by Spanish and histories can be put under the floorboards. Ezekiel becomes “Ezequiel Márquez.” Catherine becomes “Catalina.” They build a store—cloth, tools, coffee—and a life.

XIV. The Archive in the Dirt

Night after night for two decades, after the children sleep, they write. Ezequiel’s hand is steady; Catalina’s margins are precise. They assemble:

– The Thornwood Record: over 400 pages—plans, dates, rosters, maps, expenses, letters, and a confession that refuses to apologize.

– Supporting material: Marcus’s ledgers, pass-books, forged freedom papers that worked because paper rarely refuses its own.

In 1878, they bury the archive in a waterproof tin under a marked tree, with instructions to a daughter: wait until the last witness is gone and the world can bear what it refused to see.

Ezequiel dies in 1881, Catalina in 1883. Their children keep the secret the way you keep a lamp trimmed: with oil and care.

XV. Excavation: The Historian Who Listened

Monclova, Mexico, 1948. Maria Márquez de López, a granddaughter with cancer and a conscience, summons a historian known for naming things correctly: Dr. Eleanor Winters of the University of Texas. A map. A key. A warning: “This will be hated.”

They dig. Tin surfaces. Inside: handwriting that changes everything and matches everything it touches.

– County land books show a gap where Thornwood should be. An absence that becomes evidence.

– A death certificate for Marcus: “heart failure,” signed by a local doctor who preferred whiskey to autopsy.

– A will on file outlining gradual emancipation—exactly as the Record says.

– Newspaper fragments about a fire in 1856 that “eradicated a local estate.”

– Oral histories from Ruth’s descendants that track detail to detail.

Winters verifies, footnote by footnote, the way scholars swear their reputations: with dull, relentless fact. Then she publishes in 1951. The South howls. The North squints. The archive sits there, unafraid.

XVI. How to Erase a Place

Erasure is not magic. It’s bureaucracy.

– Ledger omission: one missing entry begets another. Clerks skip lines when told. Empty boxes become policy.

– Census silence: an enumerator shrugs, records a rumor, moves on. The margin wins.

– Legal smoke: a will that courts don’t want to test; a sheriff who prefers rumor; a creditor who prefers payment to scandal.

By 1860, Thornwood is a cautionary tale for white children—“the murdered plantation”—and a whispered catechism for Black elders: a place where slavery ended for a while not because Washington freed it, but because two people conspired across lines the law called God.

XVII. What Remains in the Rubble

Let’s set aside the breathless bits and weigh what’s heavy.

– Agency: Enslaved people were not waiting. They were working—teaching, networking, forging, planning. Thornwood had Ezekiel. Other plantations had their own.

– Paper as weapon: the same systems used to codify bondage—wills, ledgers, passes—can be hijacked to confound it.

– White complicity, revised: Catherine is neither absolved nor demon-only. She is what history hates most: a person who changes.

– Time as tactic: the aim wasn’t to win the South; it was to buy months for families to reposition their lives. That’s strategy, not fantasy.

What about the twelve who stayed? Not cowards—calculation. Free people get to choose risk. That’s the whole point.

XVIII. The Law They Broke—and Why It Mattered

They violated almost every statute the South treasured:

– Homicide: a master killed by his daughter and a man he owned.

– Forgery: a will that made the courts nod because it sounded like their sermons.

– Harboring: a fugitive hidden, then moved, while the law snored in paperwork.

– Miscegenation: the crime the South placed above treason because it cracked the story that whiteness was a wall.

Each violation was also a diagnosis. If your world requires these prohibitions to stand, your world is already dead.

XIX. The Seven-Month Republic

Call it a commune, a cooperative, a rehearsal. It lasted barely two seasons and still disturbs the country that buried it.

– It proved that production without terror is possible.

– It proved that whiteness can be betrayed for something better than guilt: solidarity.

– It proved that masters fear not chaos but competence in the wrong hands.

Why did it end? Because systems do what they are built to do. And because a kiss at the wrong window gave men like Sutherland their favorite story to set on fire.

XX. The Marker You Might Miss

In 1995, after local opposition that speaks for itself, a small plaque was planted on an otherwise indifferent field:

“Thornwood Plantation (1840–1856), site of a slave uprising led by an enslaved man known as Ezekiel in conspiracy with Catherine Thornwood, daughter of the owner. The rebellion resulted in the death of Marcus Thornwood and the escape of approximately thirty-five people to Mexico.”

It’s not enough. It’s also something. You can drive past it without seeing it. Or you can stop and listen: wind over grass, the lightest sound of paper turning underground.

XXI. Counterfactuals We’re Supposed to Ask

– Could they have stayed and fought in court? No court in Mississippi was going to acquit an interracial conspiracy in 1854. The law isn’t a neutral field; it’s the plantation’s other fence.

– Was murder necessary? Ask the forty-seven whose lives were scheduled around a man’s temper and debt. The comfort of alternatives belongs to people who weren’t being inventoried.

– Was love a mistake? It was an inevitability. Everything truly dangerous is.

These questions are not for absolution. They are for accuracy.

XXII. Receipts and Refrains

What we can say firmly:

– Verified: Marcus’s death certificate; the filed will; land records with gaps; a cluster of press items about a plantation fire; oral histories aligning with the Record; handwriting analysis on the archive.

– Corroborated by pattern: literate enslaved organizers, forged passes, Underground Railroad nodes south and west, Mexican sanctuary post-abolition (1829).

– Still gray: exact body count at Thornwood’s ash; the deputy’s motives; whether Cobb ever truly believed his own story.

The refrain the archive keeps singing: paperwork bends. People do, too.

XXIII. Lessons the Present Keeps Flunking

– Freedom requires infrastructure. Emancipation is not a feeling; it’s a budget, a school, a network, and time to use them.

– Attention is not care. Sutherland paid attention; Ruth cared. Only one built anything that lasted.

– The line between audience and accomplice is drawn by paperwork you sign and rumors you repeat.

– Erasure is easy. Restoration is labor.

If you want to honor Thornwood, fund the modern equivalents: legal defense for exploited workers, trusts for child performers, clinics that read contracts out loud.

XXIV. Epilogue: The Tin Box and the Door It Opens

Somewhere under a tree in Coahuila, a granddaughter pressed a key into a historian’s hand and changed the footnotes of a nation. The Thornwood Record did not make the South pure or the North honest, but it robbed both of an alibi: “We didn’t know.”

We know now that at least once a plantation stopped being itself. That men and women taught by candlelight turned documents into crowbars. That a daughter couldn’t unknow the words “created equal” once she let them in. That love is not a policy, but it is a proof.

What remains is simple:

– A field that grows whatever the county says it grows.

– A plaque the size of a book you can cover with your palm.

– An archive where two hands—one calloused, one ink-stained—wrote down a life and buried it so we could dig it up later and run our fingers along the edges.

The door isn’t wide. It’s not even fully open. But you can see through it.

📌 Quick Reference Timeline (for skimmers)

– 1848: Ezekiel purchased; “literate” noted as defect.

– 1850: Catherine returns from school to manage household accounts.

– Oct 1853: Ezekiel promoted to overseer; night lessons begin.

– Dec 1853: Federal whispers; plot accelerates.

– Jan 1854: Marcus smothered; forged will filed; Ezekiel “killed” on paper.

– Feb–Aug 1854: Thornwood operates as covert collective; productivity rises.

– Sep 1854: Fugitive Jacob sheltered; slave catchers search and fail.

– Oct 1854: Neighbor spies Catherine and Ezekiel; sheriff secures warrants.

– Oct 1854: Vote to flee; Thornwood burned; parties scatter west.

– Feb 1855: Thirty cross into Mexico; new lives begin; the Record is written over decades.

– 1878: Archive buried with instructions.

– 1948–1951: Archive excavated and verified; publication ignites debate.

– 1995: Historical marker installed after local resistance.

If this kind of reconstructed history grips you, save this piece, share it with someone who reads footnotes for sport, and keep a weather eye on the quiet places where records go to hide. Some stories don’t sleep—they wait.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load