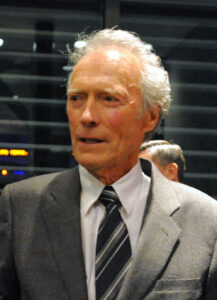

When Clint Eastwood rode into the town of Lago in 1973’s High Plains Drifter, audiences thought they knew what to expect: a dusty Western, a stoic gunslinger, and a showdown between good and evil. But beneath the familiar trappings, Eastwood’s second directorial effort concealed a vision far stranger—and far darker—than anyone imagined. Today, more than fifty years later, the film’s legacy endures not just as a box office hit, but as a chilling meditation on guilt, vengeance, and the blurry line between justice and cruelty.

The Western Rides Into New Territory

By the early 1970s, the Western genre was on life support. The heyday of John Wayne and Gary Cooper was over, and Hollywood was turning its attention to gritty crime dramas and blockbuster spectacles. So when Eastwood—best known for his iconic “Man With No Name” in Sergio Leone’s spaghetti Westerns—announced he would direct and star in a new American Western, skeptics doubted he could revive a genre many considered obsolete.

With a modest $5.5 million budget, Eastwood shot High Plains Drifter in the eerie, remote landscapes of Mono Lake, California, constructing the entire town of Lago from scratch. The result was a raw, authentic atmosphere that far outstripped its budget. Audiences responded: the film grossed more than $15.7 million domestically, nearly tripling its cost and proving the Western wasn’t dead—at least, not yet.

But High Plains Drifter was never just about box office returns. From its opening frames, it signaled something new and unsettling.

A Stranger Rides In—And Upends the Western Myth

The film opens with a lone rider emerging from the shimmering desert heat, his identity concealed and his silence menacing. Eastwood’s character—the Stranger—wasn’t a white-hatted sheriff or noble settler. He felt haunting, even spectral. Once he arrived in Lago, the story grew darker still.

Audiences accustomed to clear lines between heroes and villains were alarmed. Instead of a triumph-of-good-over-evil narrative, they got a revenge tale laced with surrealism and gothic undertones. The townspeople were no innocents; they had stood by while their marshal, Jim Duncan, was brutally murdered. The Stranger’s mission wasn’t to save them—it was to punish, humiliate, and force them to confront the guilt they had buried.

For those expecting another round-up from Eastwood’s “Man With No Name,” it was a shock. But forging a new path was precisely Eastwood’s intent. He wanted to move away from Leone’s stylized vision and create a Western with American Gothic imagery and moral ambiguity.

Eastwood’s Dual Role: Star and Director

By 1973, Eastwood was already a Hollywood icon, but directing was new territory. High Plains Drifter was only his second film behind the camera, after Play Misty for Me (1971). Directing yourself is notoriously difficult, but Eastwood had quietly studied masters like Leone and Don Siegel, learning how to shape scenes, control tone, and build tension.

His influence was visible everywhere. He chose Mono Lake for its jagged, unsettling beauty and built Lago as a warped, dreamlike town—a visual metaphor for corruption and guilt. Eastwood’s directing style was lean and efficient, often favoring spontaneity and authenticity over endless rehearsals.

Key to his success was cinematographer Bruce Surtees, who helped Eastwood balance his roles in front of and behind the camera. Together, they crafted a film where every shot, every shadow, and every silence deepened the sense of unease.

The Mystery at Lago’s Heart

At the heart of High Plains Drifter lies one of Eastwood’s most enduring mysteries: Who is the Stranger? Is he a man, a myth, a ghost, or an agent of vengeance? From his first appearance, the Stranger radiates unease, gunning down thugs with cold efficiency and treating the townspeople with contempt.

Lago itself is more than a setting; it’s a character steeped in rot and guilt. Its people, complicit in Duncan’s murder, have built their community on buried shame. Into this guilty town rides the Stranger—a force less interested in protection than in judgment.

Eastwood never clarifies the Stranger’s identity. Some viewers see him as the ghost of Marshal Duncan; others view him as a supernatural avenger or a man exploiting the town’s secret. The film sustains all three readings at once, tying the Stranger’s role tightly to Lago’s corruption and redefining what a Western protagonist could be.

Justice or Vengeance? The Film’s Haunting Questions

Traditionally, Western heroes restored order—lawmen like Wayne and Cooper embodied fairness and civilization. Eastwood dismantled that myth. His Stranger carries no badge and answers to no law. Instead, he serves a primal force: retribution.

When the Stranger humiliates Lago’s people, paints the town blood red, and forces them to rename their hotel “Hell,” he isn’t acting out of righteousness but cruelty. Justice here is not about restoring order; it’s about forcing the guilty to live inside their own corruption.

The film’s most striking theme is justice warped into vengeance. Is vengeance justice? Audiences sympathize with the Stranger’s contempt, but as he torments the townsfolk, redemption gives way to sadism. Eastwood blurs the line between avenger and villain, leaving viewers to wonder if true justice can exist in a world as compromised as Lago.

Behind the Scenes: Eastwood’s Vision and Controversy

Eastwood conceived the film as a morality play cloaked in dust and violence. He wanted to disturb audiences, not reassure them. Working with Surtees, he drenched Lago in oppressive shadows, turning the desert into purgatory. The blood-red paint and “Hell” sign weren’t just plot points—they were metaphors for damnation.

He also redefined cinematic violence, stripping away Leone’s operatic shootouts and filming brutality with cold detachment. Violence was never glamorous, even when carried out by a supposed hero.

Critics were divided. Roger Ebert praised the film as “a morality play disguised as a Western,” while others dismissed it as bleak and sadistic. Locals in Mono Lake objected to Lago being portrayed as cowardly and corrupt, but Eastwood insisted the film was a condemnation of frontier hypocrisy—not a tribute.

Legacy: A Genre Transformed

Over time, High Plains Drifter’s reputation grew. What was once condemned as nihilism seemed prophetic in the era of Vietnam and Watergate. The film became a touchstone for revisionist Westerns, paving the way for Eastwood’s later masterpieces like Unforgiven and Pale Rider.

Eastwood has called the film a fable—a ghost story about conscience and guilt. “If you’re haunted by guilt, the ghosts are real enough,” he once said, refusing to define the Stranger and deepening the film’s mystique.

Today, High Plains Drifter stands as a milestone in Eastwood’s career—a film that crowned him not just as a star, but as a serious filmmaker. Its haunting imagery, moral ambiguity, and refusal to offer easy answers continue to unsettle and provoke, reminding us that justice is never clean, and that the ghosts of our past are never far behind.

What Do You Think?

What’s your take on the hidden meaning behind High Plains Drifter? Share your thoughts in the comments below. Don’t forget to like, subscribe, and stay tuned for more untold Hollywood stories—the next mystery is already waiting on the screen.

News

The Scene That Took Happy Days Off the Air for Good

“Happy Days Betrayed: The Secret Finale Disaster That Shattered TV’s Most Beloved Family—How ABC’s Blunder Turned a Classic Into a…

Before Death, Moe From 3 Stooges Broke Silence On Curly And It’s Bad

“The Dark Secret Moe Howard Took to His Grave: The Heartbreaking Truth Behind Curly’s Tragic Fall” Hollywood’s Golden Age was…

This Photo Is Not Edited, Look Closer At The Young Frankenstein Blooper

Comedy Gold by Accident: The Unscripted Genius Behind ‘Young Frankenstein’s’ Funniest Moments When it comes to classic comedy, few films…

Liberty GM Hints They WON’T Be Resigning Natasha Cloud Next Season…

Liberty at a Crossroads: Inside New York’s Bold Backcourt Shakeup and the GM’s Proactive Vision for Sabrina Ionescu’s Future The…

The Heartbreaking Tragedy Of Drew Scott From Property Brothers

Fame, Fortune, and the Hidden Battles: The Untold Story of Drew Scott’s Rise, Fall, and Triumphant Return Drew Scott—the cheerful…

Indiana Fever INTENSE PRACTICE Before Game 3 Semifinals vs. LV Aces! Caitlin Clark, Hull, Boston

Indiana Fever Ramp Up Intensity Ahead of Semifinal Clash with Las Vegas Aces: Caitlin Clark Leads Fiery Practice, Injury Updates…

End of content

No more pages to load