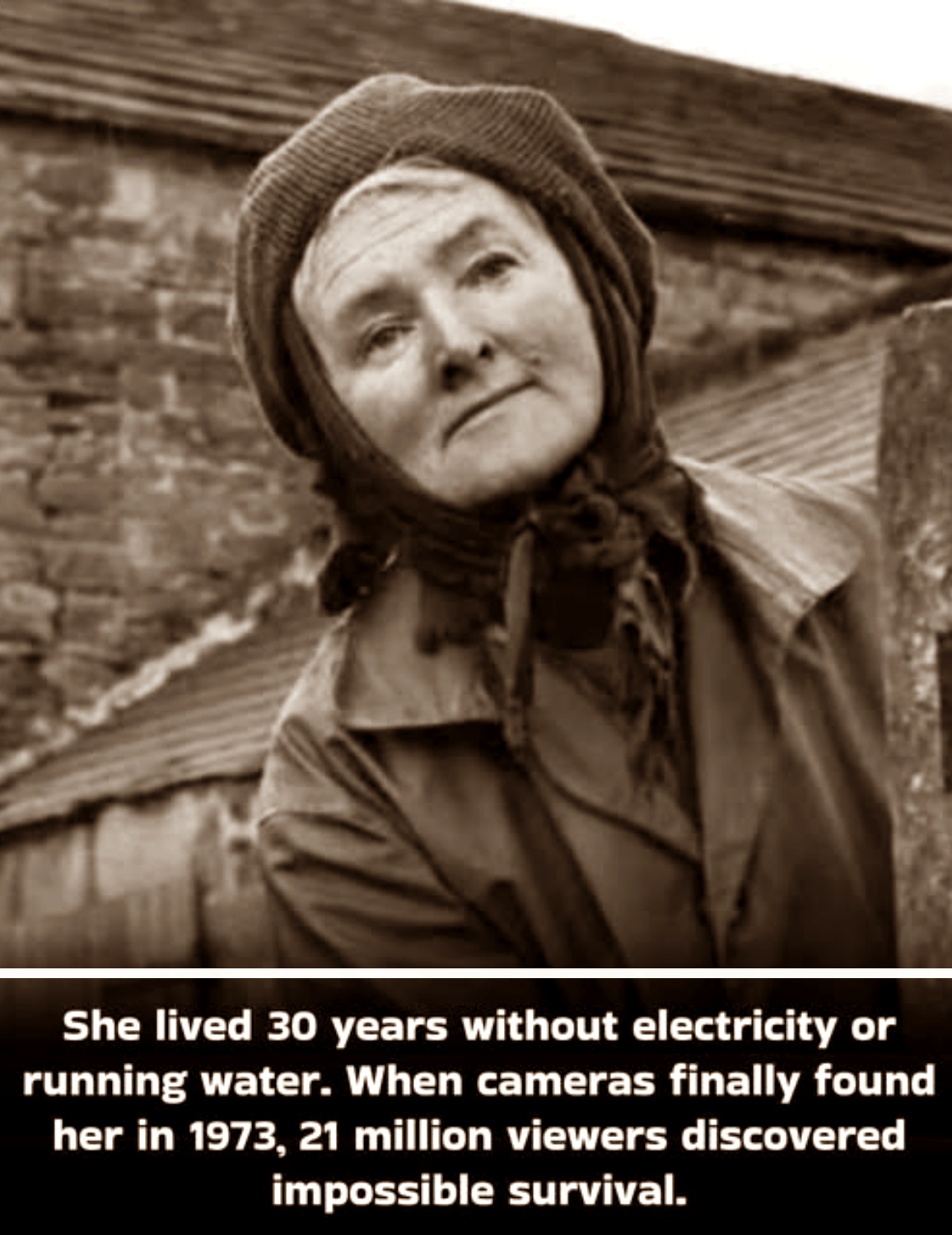

The camera crew expected to film poverty. What they found was a 47-year-old woman who had lived without electricity, running water, or human touch for decades—and didn’t know life could be any different.

When Too Long a Winter aired in 1973, 21 million people watched. And Hannah Hauxwell discovered she’d been surviving what most would call impossible.

But before the cameras, before the letters, before Britain fell in love with the woman from the High Pennines—there was just a girl watching everyone leave.

Hannah Hauxwell was born in 1926 on Low Birk Hatt Farm, 1,100 feet above sea level in the Yorkshire Dales. It was remote even by farming standards—no road access, no neighbors within shouting distance, no electricity lines running anywhere near the stone farmhouse that had stood since the 1600s.

Her childhood was work. Feeding animals before dawn. Hauling water from the spring. Helping her father with the cattle in winds so strong they knocked children off their feet. The Pennines weren’t picturesque—they were brutal. Winter temperatures dropped to -20°C. Snow buried fences. Lambs froze in the fields.

But there were people. Her parents. Her uncle. Neighbors who would stop by after market day. The postman who came twice a week. Human voices. Human warmth.

Then they started dying.

Her father died when Hannah was young. Her uncle died shortly after. By her twenties, it was just Hannah and her mother, two women trying to maintain an 80-acre farm that required three men’s labour.

They kept cattle—not many, maybe a dozen at most. Just enough to generate minimal income. Hannah would milk them by hand every morning in the drafty stone barn, her fingers going numb in the cold. She would carry the milk in heavy pails back to the house. She would skim the cream. She would walk three miles to the nearest road to meet the milk truck.

Then she’d walk back and start the rest of the day’s work.

Her mother died in 1958. Hannah was 32 years old. And then there was no one.

Most people would have sold the farm immediately. The land was worth something—not much, but enough to buy a small house in a village, to start over somewhere with electricity and shops and people.

Hannah stayed.

Not because she loved the isolation. Not because she was making money—she wasn’t. The farm barely generated £200 a year, roughly £4,000 in today’s money. That’s what she lived on. For everything. Food, clothes, animal feed, repairs.

She stayed because it was what she knew. Because leaving felt like admitting defeat. Because the farm had been in her family for generations, and abandoning it felt like betraying everyone who’d worked the land before her.

So Hannah Hauxwell, alone at 32, decided to keep farming. Here’s what that meant:

WINTER: Temperatures inside the farmhouse regularly dropped below freezing. She had no central heating—just a single coal fire in the kitchen that she kept burning constantly because if it went out, restarting it meant an hour of work with frozen fingers. She slept in all her clothes, including her coat. She would wake to find ice on the inside of the windows. Water left in a cup overnight froze solid.

WATER: There was no running water. Every drop came from a spring 100 yards from the house. In summer, this meant multiple trips carrying heavy buckets. In winter, this meant breaking through ice, filling buckets with numb hands, and carrying them back before they froze again. Washing meant heating water on the stove—a process so time-consuming and fuel-expensive that she bathed once a week at most.

FOOD: She had no refrigerator. She grew vegetables in summer and preserved what she could. In winter, she lived on potatoes, bread, and whatever meat she could afford—often nothing. Neighbors later recalled that Hannah was always thin, always looked tired, always wore the same patched clothes year after year.

ANIMALS: The cattle needed feeding twice a day, every day, regardless of weather. Hannah would wade through waist-deep snow to reach the barn. She would fork hay from storage—hard, physical labor that left her exhausted. She would break ice in the water troughs. She would check for illness, injury, birthing complications. Alone. Always alone.

LONELINESS: This might have been the hardest part. Days would pass without seeing another human being. Weeks in winter. The postman came when roads were passable—sometimes that meant not for a month. She had no telephone. No radio (it required electricity). No television. Just silence, wind, and the sound of her own breathing. She was living in conditions that most of Britain thought had vanished a century earlier.

And no one knew.

In 1972, a young ITV producer named Barry Cockcroft was researching a documentary about rural poverty in Northern England. Someone mentioned a woman living alone on a remote Pennine farm “in Victorian conditions.”

Cockcroft was skeptical. This was 1972. Britain had the NHS, the welfare state, electrification programs. Surely no one was actually living without basic utilities by choice. He drove to Low Birk Hatt Farm to investigate.

The farm had no road access. He had to park a mile away and walk across fields. He knocked on a wooden door that looked like it hadn’t been painted in decades.

Hannah Hauxwell answered.

Cockcroft later said the thing he remembered most was her hands—red, chapped, with scars from barbed wire and work injuries that had never properly healed.

She was 46 years old but looked 60. She was thin—alarmingly thin. Her clothes were patched and re-patched. Behind her, he could see the dim interior of a house lit only by daylight and a single coal fire.

She invited him in for tea.

As they talked, Cockcroft realized this wasn’t a story about poverty in the way he’d imagined. Hannah wasn’t a victim asking for help. She wasn’t bitter about her circumstances. She spoke matter-of-factly about her life: the animals needed feeding, the water needed hauling, the work never stopped.

She had no idea her life was unusual.

Cockcroft asked if he could film a documentary. Hannah agreed, mostly because she was too polite to refuse.

Too Long a Winter aired on January 3, 1973, at 9 PM on ITV.

21 million people watched.

The footage was stark: Hannah waking before dawn in a freezing house. Hannah carrying buckets of water through snow. Hannah eating a sparse meal alone at a bare wooden table. Hannah describing, in her soft Yorkshire accent, what winter was like: “Sometimes the snow is so deep you can’t get out at all. You just have to wait.”

There was no music. No narration trying to make the story more dramatic. Just Hannah, living.

The reaction was immediate and overwhelming. Thousands of letters arrived at the farm. People sent money—donations ranging from a few pounds to hundreds. A local businessman offered to install electricity for free. Others sent clothes, food parcels, offers of help.

The media descended. Newspapers wanted interviews. Other documentaries were commissioned. Hannah appeared on talk shows. She was invited to events in London—her first time ever leaving Yorkshire.

Britain had fallen in love with Hannah Hauxwell. But not because she was pitiable. Because she was dignified.

In every interview, she never complained. She never blamed anyone. She never asked for pity. She simply described her life as it was, and viewers recognized something profound: this was a person who had endured decades of hardship without losing her humanity.

She became a symbol—of self-sufficiency, of rural resilience, of a disappearing way of life. But also of something deeper: the quiet strength of people who endure without an audience, who keep going not for recognition but because the work needs doing.

With the donations, Hannah finally installed electricity in 1973. She was 47 years old. For the first time in her life, she could flip a switch and have light. She could have heat without hauling coal constantly. She could have a refrigerator, a radio, a connection to the world.

But she didn’t dramatically change her lifestyle. The animals still needed feeding. The water still needed hauling (running water would have required extensive plumbing work she couldn’t afford). The isolation remained.

More documentaries followed over the next two decades: A Winter Too Many (1988), Hannah’s North Country (1988). Each one showed an older Hannah, still farming, still alone, but now with electricity and modest improvements.

Viewers watched her age. They watched winters take their toll. They watched her struggle with tasks that had once been merely difficult but were now nearly impossible.

By the early 1990s, Hannah was in her mid-60s. Her body, worn down by decades of brutal physical labor, couldn’t sustain the work anymore. Cattle needed strength to manage. Water needed strength to carry. The farm needed someone younger, stronger.

In 1988, Hannah made the decision that everyone had been expecting for years: she would sell the farm and move to a cottage in the village of Cotherstone, about 5 miles away—but a world away in terms of comfort and access.

The announcement made national news.

The sale of Low Birk Hatt Farm felt like the end of an era—not just for Hannah, but for a way of life that was vanishing from Britain. Small hill farms couldn’t compete with industrial agriculture. Young people weren’t staying in rural areas. The old ways were dying.

Hannah moved into a small cottage with central heating, running water, and a proper bathroom. After 60 years of hauling water and sleeping in her coat, she finally had comfort.

She lived there for another 30 years.

In her later years, Hannah became something of a rural celebrity. She wrote books about her life. She traveled—something she’d never imagined doing. She visited the Dales again, this time as a visitor rather than a prisoner of the land.

She gave interviews about resilience, about simplicity, about the value of quiet perseverance. She was always uncomfortable with the attention, always insisting she’d “just done what needed doing.”

Hannah Hauxwell died in 2018 at the age of 91.

The obituaries called her “the last of the hill farmers,” “a symbol of rural Britain,” “an inspiration to millions.” They showed clips from Too Long a Winter—Hannah carrying those buckets of water, feeding those cattle, sitting alone in that cold house.

But here’s what the obituaries often missed:

Hannah Hauxwell didn’t choose that life out of some romantic attachment to simplicity. She was trapped by circumstance—by poverty, by isolation, by lack of options, by societal expectations that women should maintain family farms even when it destroyed them.

Her endurance wasn’t inspirational in the way people wanted it to be. It was survival. It was the absence of alternatives. It was what happened when someone fell through the cracks of the welfare state, when rural isolation meant invisibility, when pride prevented asking for help.

What was inspirational was what happened when the cameras finally arrived: Hannah didn’t perform suffering for sympathy. She didn’t exaggerate her hardships. She simply showed her reality—and that reality was powerful enough to move 21 million people.

She didn’t ask viewers to pity her. She asked them—without ever saying it explicitly—to see her as fully human. To recognize that dignity doesn’t require comfort, that strength doesn’t require recognition, that value doesn’t require validation.

And Britain saw her.

The letters, the donations, the electricity installation—these weren’t charity for a victim. They were a collective acknowledgment: “You shouldn’t have been invisible. We should have known. We should have cared sooner.”

Hannah accepted the help gracefully, used it practically, and continued living as she always had—with quiet determination and without complaint.

She didn’t inspire people by overcoming her circumstances in some dramatic fashion. She inspired them by simply continuing, day after day, without an audience, without applause, without any assurance that anyone would ever know.

For 30 years, Hannah Hauxwell carried water in the freezing cold. Not because she wanted to prove something. Because the animals needed water. Because she needed water. Because the work existed and someone had to do it.

Most people discovered her in 1973. But she’d been there all along—unseen, unheard, but absolutely present.

The documentary didn’t make her remarkable. It made her visible.

She was 47 when the world finally noticed she’d been surviving the impossible. She was 62 when she finally stopped. She was 91 when she died, having lived three decades of the comfort she’d been denied for six.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load