By the end of the 1930s, Austria was a country adrift between glamour and ruin. Vienna, once a jewel of empire, was now a fading stage — the music still played, the chandeliers still glowed, but behind the velvet curtains, fear and poverty quietly returned.

In this uneasy calm, the newspapers turned into theaters of distraction.

Readers craved anything that could make them forget the march of soldiers or the new flags rising over rooftops.

That’s when they met her.

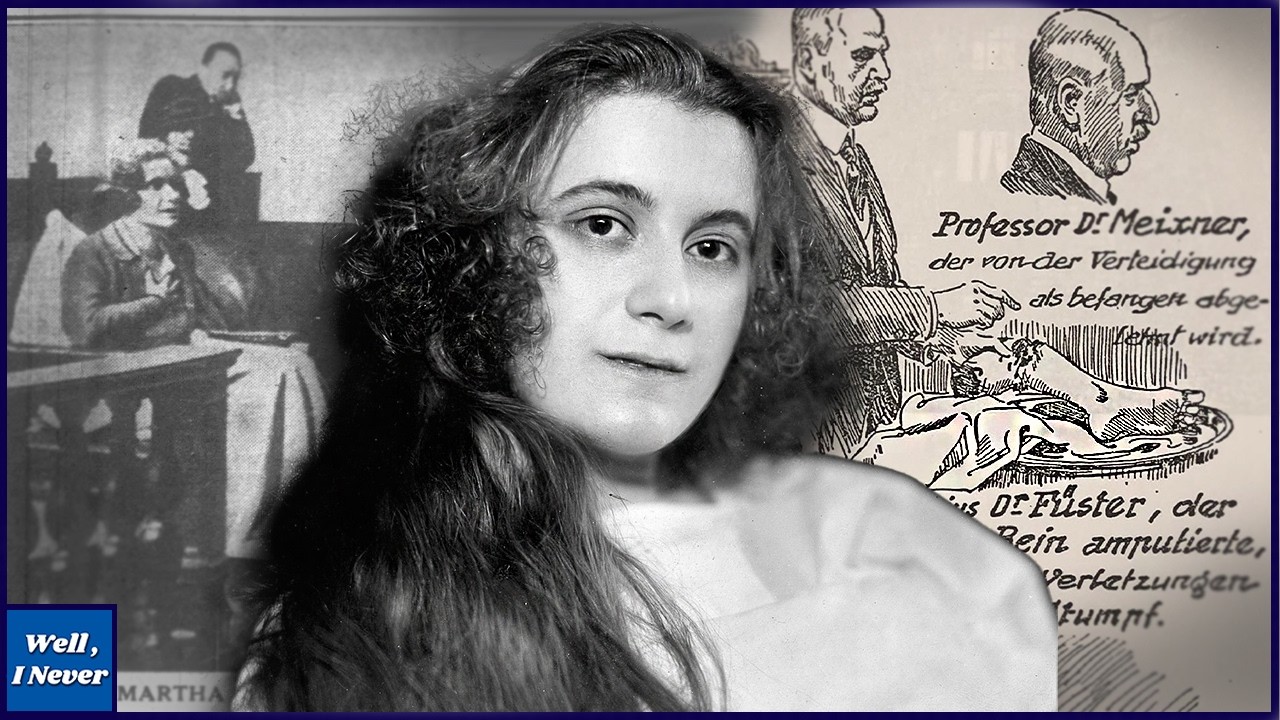

Martha Marik’s name appeared beneath headlines dripping with curiosity and disbelief. Reporters called her “The Beautiful Widow,” “The Ice Queen,” and finally, “The Woman Who Fooled the Empire.”

But before the scandal, before the trials and the tabloids, Martha was simply another poor girl from Vienna’s working-class neighborhoods.

Born sometime between 1897 and 1904 — no one could even agree on the date — she grew up in a world where poverty shaped every dream. Her father vanished early; her mother, overwhelmed, reportedly gave Martha away to be raised by another family.

At twelve, she came back — a sharp-eyed child with no patience for fairy tales. She worked as an errand girl in a dressmaker’s shop, carrying bolts of fabric through the grand boulevards of Vienna. Every day she watched elegant women sweep past in silk and pearls, and every day she swore she’d join them — somehow.

Her chance came in the most unlikely way.

One rainy afternoon, while delivering a parcel, she met Moritz Frick, an aging department-store magnate nearly fifty years her senior. He noticed the hungry look in her eyes — not for food, but for more.

Their relationship blurred the line between mentorship, protection, and something darker. Within a few years, Frick had taken her into his home, dressed her in French gowns, and sent her to finishing schools in Paris and London.

Vienna’s society whispered, but Martha didn’t care. She had learned the city’s first rule: image was everything.

When Frick died suddenly in 1923, the papers called her “the lucky girl.”

She inherited his villa, his jewels, and his fortune. At not yet thirty, Martha was rich — and free.

Soon after, she met Emil Marik, a handsome engineering student with big ideas and bigger debts. They married quickly.

But wealth, as Martha learned, was never enough to feel safe — not in a world that could change overnight.

In 1925, Emil and Martha took out a life and disability insurance policy — a common move for young couples of their standing. But the amount raised eyebrows: the payout for permanent injury was enormous, equal to nearly half a million dollars today.

And then, the impossible happened.

Just days after the policy took effect, Emil suffered a “tragic accident.”

According to Martha, he had been chopping wood when the axe slipped, nearly severing his leg.

The doctors who arrived found the wound horrifying — too clean, too precise, almost deliberate. But the story stuck. Emil lived, though he would never walk the same way again.

The insurance company, suspicious, launched an investigation. They discovered multiple cuts on the limb, suggesting the leg had been struck several times. It looked less like an accident, and more like… something else.

Still, the Mariks stood their ground. Martha, poised and tearful, told the court her husband’s life had been shattered by misfortune. Emil sat beside her, the picture of tragic nobility.

The public adored them.

In a city weary of corporate greed, the idea of a heartless insurance company bullying a wounded man and his beautiful wife made for irresistible headlines.

When the verdict came — guilty of minor corruption, but cleared of major fraud — Vienna erupted in applause. The glamorous couple walked free, their reputation intact.

And the insurance company, fearing more bad press, quietly paid them a settlement worth nearly a million dollars in today’s money.

For a while, they lived like royalty. Emil left his engineering dreams behind. Martha hosted soirées, wore Parisian perfume, and collected admirers like jewelry.

But money, in their hands, melted fast. Within a few years, the villa grew quieter, the servants disappeared, and the lights dimmed. Emil struggled to find work. Martha gave birth to two children, Ingeborg and Alons, but motherhood didn’t slow her restlessness.

Then came sickness.

First Emil — pale, thin, and fading. Then their daughter. Both gone within months. Each time, Martha received small insurance payouts. Each time, she remained strangely composed.

By 1934, her name began to circulate again — this time with unease.

When her wealthy aunt invited her to move in, Martha seemed reborn. She promised to care for the old woman in her final years. Instead, the woman’s health collapsed within months. Another inheritance. Another funeral.

Neighbors whispered. Doctors frowned. But no one could prove a thing.

By 1936, money troubles returned. Martha began renting rooms in her villa, taking in a seamstress named Felicitas Kittenberger. The two women shared tea, gossip — and soon, tragedy. Felicitas fell ill with strange symptoms: trembling, hair loss, weakness. Within weeks, she was gone.

Again, an insurance policy appeared. Again, Martha was the beneficiary.

When police later investigated a “burglary” at Martha’s home, the story began to unravel. The stolen paintings? Found safe in a warehouse — where Martha herself had delivered them.

It was sloppy, almost arrogant. She was arrested for fraud.

That’s when the real horror surfaced.

Felicitas’s son read about the arrest and contacted police, insisting his mother had been poisoned. Investigators exhumed the bodies of Emil, his daughter, the aunt, and Felicitas. Every one of them tested positive for thallium — a deadly metal found in rat poison.

The press exploded.

“The Poison Widow of Vienna!” screamed one headline.

“She Killed for Comfort,” said another.

Martha denied everything, but the timing couldn’t have been worse. In 1938, Nazi Germany annexed Austria, seizing control of the courts and the media. The regime, eager for spectacle, turned Martha’s trial into propaganda — a cautionary tale of greed and moral decay.

She became both criminal and scapegoat: a woman to be hated, mocked, and displayed.

During the trial, she alternated between fainting, shouting, and mocking the judge. Witnesses described her cold laughter. A pharmacist testified that she had bought enough rat poison “to kill an army.”

The jury — five citizens and four Nazi-appointed judges — returned a guilty verdict. The sentence: death.

Even in those days, death sentences for women were rare. But Austria was no longer Austria. The guillotine had been shipped from Berlin, and the Nazis wanted examples.

On a cold December morning in 1938, Martha Marik was wheeled into Vienna’s Regional Court. Guards tied her down as reporters scribbled notes.

Minutes later, the blade fell.

Her story vanished almost overnight. Within months, Europe was at war. Millions would die. One woman’s crimes, however chilling, became a footnote.

Today, her name survives only in fragments — yellowed newspaper clippings, half-remembered memoirs, and a few lines in crime history books.

But the story of Martha Marik is more than a scandal; it’s a mirror. It shows how chaos breeds deception — how a world obsessed with appearances can turn survival into theater.

In a city drowning in propaganda, poverty, and fear, she learned to play every role: the orphan, the heiress, the victim, the widow.

And for a time, she fooled them all.

The lesson isn’t just about greed — it’s about belief.

How much do we want a story to be true, when it distracts us from everything else falling apart?

In 1938, Austria wanted villains they could understand. Martha gave them one.

And in doing so, she slipped quietly into history — the woman who fooled Vienna, one last time.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load