In 1963, before she was famous, Gloria Steinem went undercover as a Playboy Bunny. What she found behind the glamour launched a movement. Her exposé changed everything.

THE ASSIGNMENT

New York City, 1963.

Gloria Steinem was 28 years old, a freelance journalist scraping by on whatever assignments she could get. She had a degree from Smith College, she was smart and capable, but in the early 1960s, that didn’t matter much if you were a woman.

While male reporters got assignments covering politics, crime, and breaking news, Gloria got fashion pieces. Beauty tips. Fluff.

Then Show magazine offered her something different: go undercover at the New York Playboy Club. Pose as a wannabe Bunny. Write about what it’s really like behind the scenes.

The ads for Playboy Club jobs made it sound like a dream: “Yes, it’s true! Attractive young girls can now earn $200-$300 a week at the fabulous New York Playboy Club…”

From the street, it looked glamorous—sparkling lights, famous faces, clinking glasses, beautiful women in satin costumes serving drinks to powerful men.

But Gloria Steinem was about to learn what “glamour” actually cost.

THE AUDITION

She adopted a fake name—Marie Ochs, using her grandmother’s name and social security number—and applied for a job.

The application process itself was revealing. Two interviews. A tryout in costume. A fitting for false eyelashes. Then came the physical examination.

The women were required to undergo internal gynecological exams and blood tests for venereal disease—procedures they were told were mandated by the state. They weren’t. It was a lie. CBS News

Then came “Bunny School”—two indoctrination sessions where new hires learned the drink-serving rituals, studied the “Bunny Bible” of rules, and received lectures from the “Bunny Mother” and “Bunny Father” about proper behavior.

Nearly all Bunnies were required to stuff their bosoms to achieve the desired look. NyuNyu The costume had to fit perfectly. The tail had to be fluffy. The smile had to be constant.

Gloria was hired and assigned to start immediately—first at the hat-check stand, then “on the floor” serving drinks.

THE REALITY

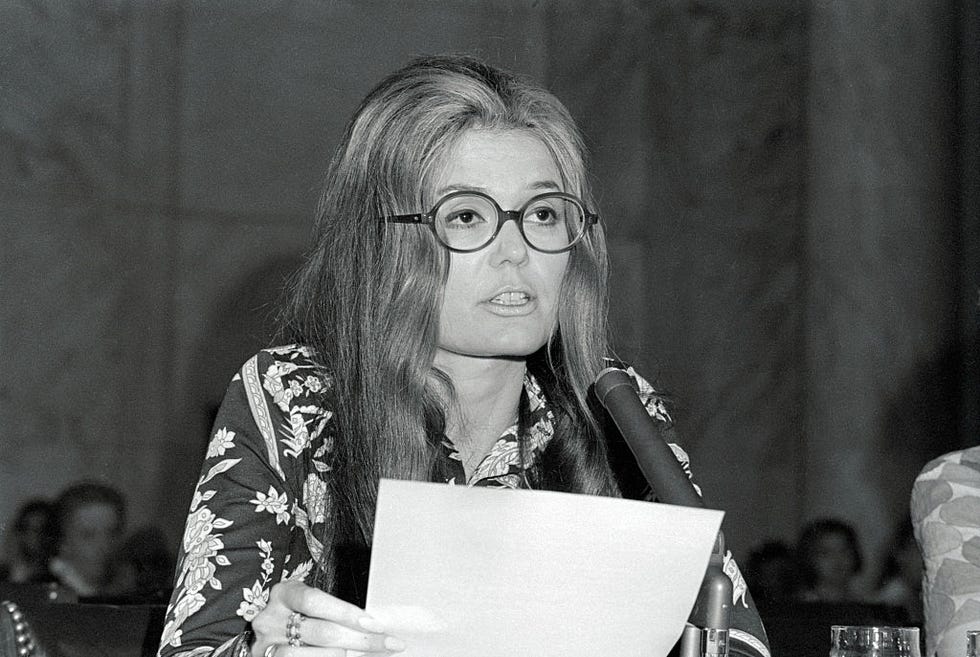

For eleven days, Gloria Steinem worked as “Bunny Marie.” HISTORY

What she found was exhausting, degrading, and nothing like the glamorous image sold to the public.

The shifts were brutal—long hours on her feet in uncomfortable heels and a restrictive costume. The promised wages of $200-$300 per week? A lie. The actual pay was far less. CBS News

There was a system of demerits—marks given for infractions like refusing to go out with a customer “in a rude way,” even though Bunnies were strictly forbidden from dating most customers. The rules were impossible to follow, designed to keep the women anxious and compliant.

The harassment was constant. Customers grabbed. They propositioned. They treated the Bunnies like objects they’d paid to touch.

And through it all: keep smiling. Keep the tail fluffy. Don’t gain an ounce. Don’t complain. Don’t be human.

THE EXPOSÉ

On May 1, 1963, Show magazine published the first half of “A Bunny’s Tale.” HISTORY The second part followed shortly after.

Gloria’s article stripped away the satin curtain and showed what was really happening inside Hugh Hefner’s empire. It wasn’t sexy. It wasn’t fun. It was exploitation dressed up as opportunity.

The piece was one of the first feminist attacks on Playboy and the “sexually liberated” but male-centric lifestyle it embodied. HISTORY

The public response was immediate. Hugh Hefner tried to take it in stride, claiming that applications to work at the Playboy Club had actually increased thanks to Steinem’s article—and that Playboy was on the side of women’s liberation. HISTORY

But he also quietly changed some policies. He ordered the club to stop giving new Bunnies mandatory blood tests and gynecological exams—the invasive procedures Steinem had questioned in her article. HISTORY

Working conditions improved, at least marginally.

But for Gloria Steinem, the article became both a blessing and a curse.

THE AFTERMATH

The exposé made her famous—but not in the way she wanted.

For years afterward, she was haunted by photos of herself in the Bunny costume. The piece led to no serious new assignments—instead, she was flooded with offers to take on sexualized undercover roles. Nyu

She turned down an advance for a book contract to expand the idea. She rejected an assignment to expose high-end prostitution by posing as a call girl—an idea she found “as insulting as it was frightening.” Nyu

For a long time, Steinem saw her eleven days as Bunny Marie as a huge career blunder. It became her least-favored but most-invoked characterization—the thing people remembered when they wanted to diminish her.

“Oh, you’re the Bunny girl,” they’d say, as if that’s all she was.

But Gloria Steinem was just getting started.

THE MOVEMENT

The 1970s transformed her from a frustrated journalist into the voice of a generation.

She co-founded Ms. magazine in 1971—a publication by women, for women, about the issues that actually mattered: reproductive freedom, workplace equality, domestic violence, sexual harassment, childcare, equal pay.

She marched. She organized. She spoke on stages across the country, even though she was an introvert who hated public speaking. She carried the weight of millions of women who’d been told to shut up and smile.

Critics tried to reduce her. “Too pretty to be taken seriously.” “Too radical to be practical.” But she kept going.

She gave women language for what had been silenced. She made the “small” stories—the ones about secretaries and waitresses and housewives—speak for millions.

If they wouldn’t let her through the front door, she built another one.

THE LEGACY

In later years, Gloria Steinem said she didn’t regret writing “A Bunny’s Tale” because “it did improve working conditions” and “exposed it as tacky, which it really was.” CBS News

The piece that had seemed like a career-killer became one of the most famous examples of undercover journalism in American history. It’s remembered as one of “the most amusing and talked about of undercover exploits.” Nyu

A 1985 TV movie, A Bunny’s Tale, starring Kirstie Alley as Steinem, introduced the story to a new generation.

But the real legacy isn’t the article itself—it’s what came after.

Gloria Steinem showed that you could slip into a costume, adopt a fake name, endure humiliation—and use that experience to change the conversation.

She proved that the “small” stories mattered. That women’s experiences—dismissed as trivial, as complaints, as “not real news”—were actually the stories that needed to be told most urgently.

She transformed invisibility into power.

THE LESSON

In 1963, Gloria Steinem was a struggling freelance writer taking whatever assignments she could get.

By the 1970s, she’d helped launch a movement that changed laws, opened doors, and gave voice to half the population.

She did it by refusing to accept the roles she was offered—fashion writer, sex object, decoration—and insisting on telling the truth instead.

Her message still echoes today: When the world tells you you’re nothing, become impossible to ignore.

Don’t wait for permission. Don’t wait for the “right” assignment. Don’t wait for men to take you seriously.

Take the costume. Take the byline. Take the microphone.

And make them listen.

Gloria Steinem. Journalist. Feminist. Revolutionary.

The woman who went undercover as a Bunny—and exposed an empire.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load