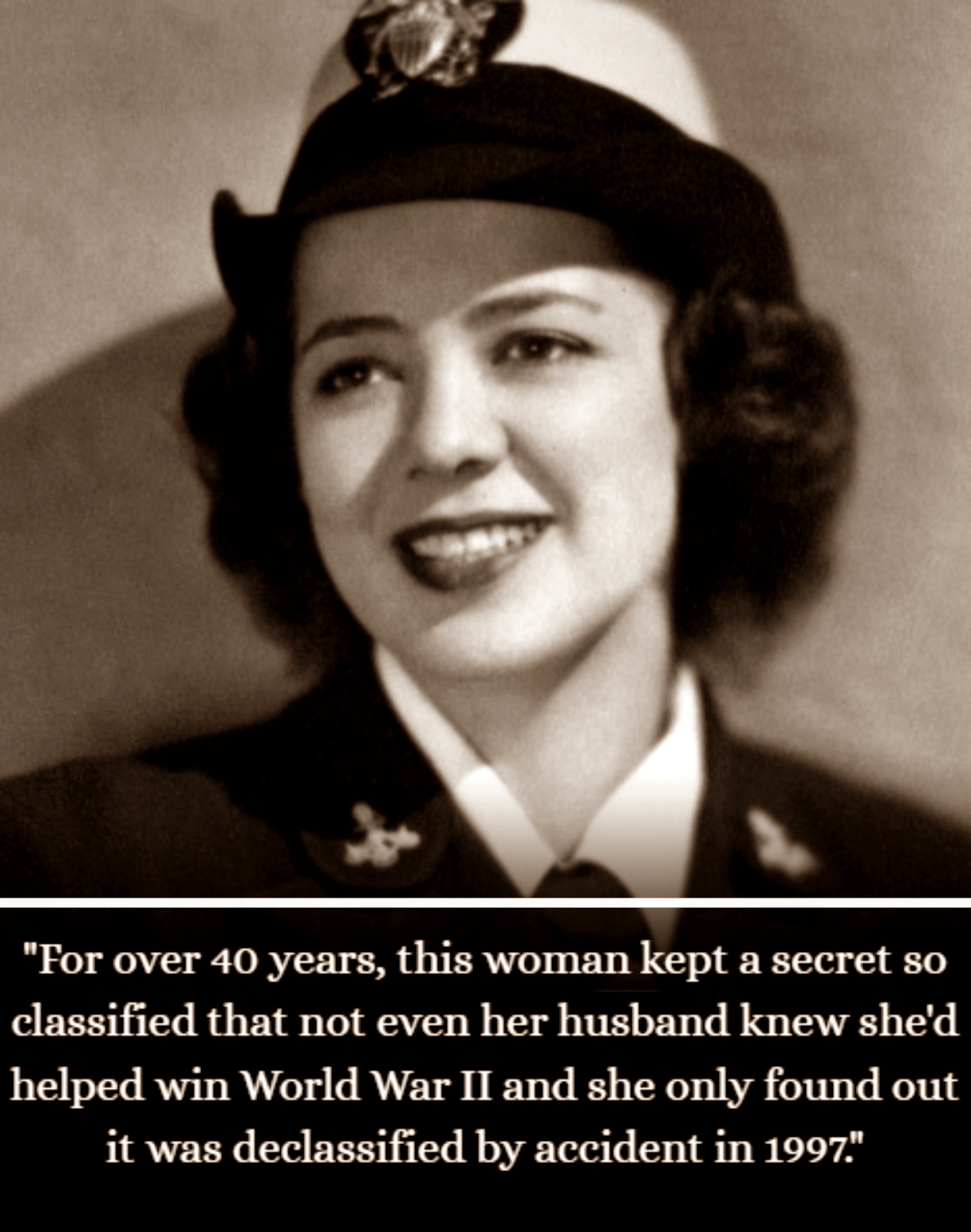

Julia Parsons passed away on April 18, 2025, at the age of 104. Until her death, she was the last surviving U.S. Navy codebreaker from World War II.

But for most of her life, almost no one knew what she had done.

In 1942, Julia Potter graduated from Carnegie Tech in Pittsburgh with a humanities degree that, as she put it, “equipped me to do practically nothing in the real world.” She briefly worked in an Army ordnance factory checking gauges on artillery shells—backbreaking work in steel mills that traditionally considered women “bad luck.”

Then she read a newspaper article that changed everything.

The U.S. Navy was accepting women for the first time ever as commissioned officers through a new program called WAVES—Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service. Julia enlisted immediately.

“There was nothing for women to do but sit at home and wait,” she later recalled. But Julia wasn’t built for waiting.

She was shipped to Washington, D.C., to the Naval Communications Annex, where she joined an all-women team in a division codenamed “Shark.” Their mission: crack the German Navy’s Enigma codes and decode U-boat communications in the North Atlantic.

The Germans believed Enigma was unbreakable. The typewriter-sized device used internal rotors to generate millions of possible codes, with settings that changed twice daily. It was mathematically impenetrable—or so they thought.

“They just refused to believe that anyone could break their codes,” said cryptography expert Thomas Perera. “Their submarines were sending their exact latitude and longitude every day.”

Julia and her team used massive Bombe machines—early computers developed from Polish and British breakthroughs—to crack the codes. Messages poured in all day from across the North Atlantic, the North Sea, and the Bay of Biscay. The women would analyze patterns, create “menus” of possible letter combinations, feed them into the Bombes, and wait for the machines to spit out the day’s wheel settings.

Then they’d decode the messages.

Sometimes it was tactical information about convoy routes. Sometimes it was U-boat positions. And sometimes… it was personal.

Julia never forgot decoding a congratulatory message sent to a German sailor celebrating the birth of his son. A few days later, Allied forces sank his submarine.

“To think that we all had a hand in killing somebody did not sit well with me,” Julia told The Washington Post decades later. “I felt really bad. That baby would never see his father.”

But she understood the stakes. Every decoded message meant Allied convoys could avoid U-boat wolf packs. Every cracked position meant submarines could be hunted and sunk. Her work directly contributed to winning the Battle of the Atlantic—the campaign that kept Britain supplied and made D-Day possible.

“This was a very patriotic time in the country,” she reflected in 2021. “Everybody did something. Everybody was patriotic. It was a beautiful time for that kind of thing.”

In 1944, Julia married Army Lieutenant Donald Parsons in the Navy Chapel in Washington. She told him she did office work for the Navy. That was all.

She kept that story for over 40 years.

After the war, Julia raised three children, earned her teaching certification, taught English at North Allegheny High School, and lived abroad in London, Japan, and Yugoslavia while her husband worked as an engineer for Westinghouse. She was a devoted mother, grandmother, and community volunteer.

And she never breathed a word about Enigma.

The work was declassified in the 1970s. But Julia didn’t know that.

In 1997, she visited the National Cryptologic Museum near Washington as a tourist, just curious about American history. She walked through the exhibits and froze.

There, on display for everyone to see, were Enigma machines. Early models. Late models. Complete explanations of how they worked. Everything she’d been sworn to secrecy about for half a century.

“The exhibits there astounded me,” she said. “Here was every sort of Enigma machine on display for all to see.”

She asked a tour guide why the machines were public. The guide explained that the Enigma project had been declassified decades earlier.

Julia Parsons hadn’t known. No one had told her. She’d kept a secret that was no longer a secret—for over 20 years.

From that moment on, she made up for lost time. She visited classrooms. She gave interviews to veterans’ groups and historians. She shared her story with anyone who would listen, inspiring new generations with tales of the women who helped crack the most sophisticated code of World War II.

“It’s been good to break the silence,” she said. “Good for me, and for history.”

In 2024, she was honored with a mention in the Congressional Record. The Pittsburgh Steelers brought her onto the field. Carnegie Mellon University recorded her oral history and let her hold the same Enigma machines she’d worked with 75 years earlier.

And every morning until her final days, Julia played Wordle on her iPad and texted the results to her children. It was their code—their way of knowing she was up and about, still sharp as ever, still solving puzzles.

When her children didn’t receive a Wordle text, they’d call: “Where’s your Wordle?”

Julia Parsons turned 104 on March 2, 2025. Six weeks later, she passed away peacefully in a Veterans Affairs hospice facility in Pennsylvania, surrounded by her children, eight grandchildren, and eleven great-grandchildren.

She was the last of the Navy codebreakers. The last of the women who sat in secret rooms decoding messages that changed the course of history. The last of a generation that served without recognition, without glory, and without complaint.

God bless Julia Parsons. God bless the Greatest Generation. And God bless all those who served in silence so that we could live in freedom.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load