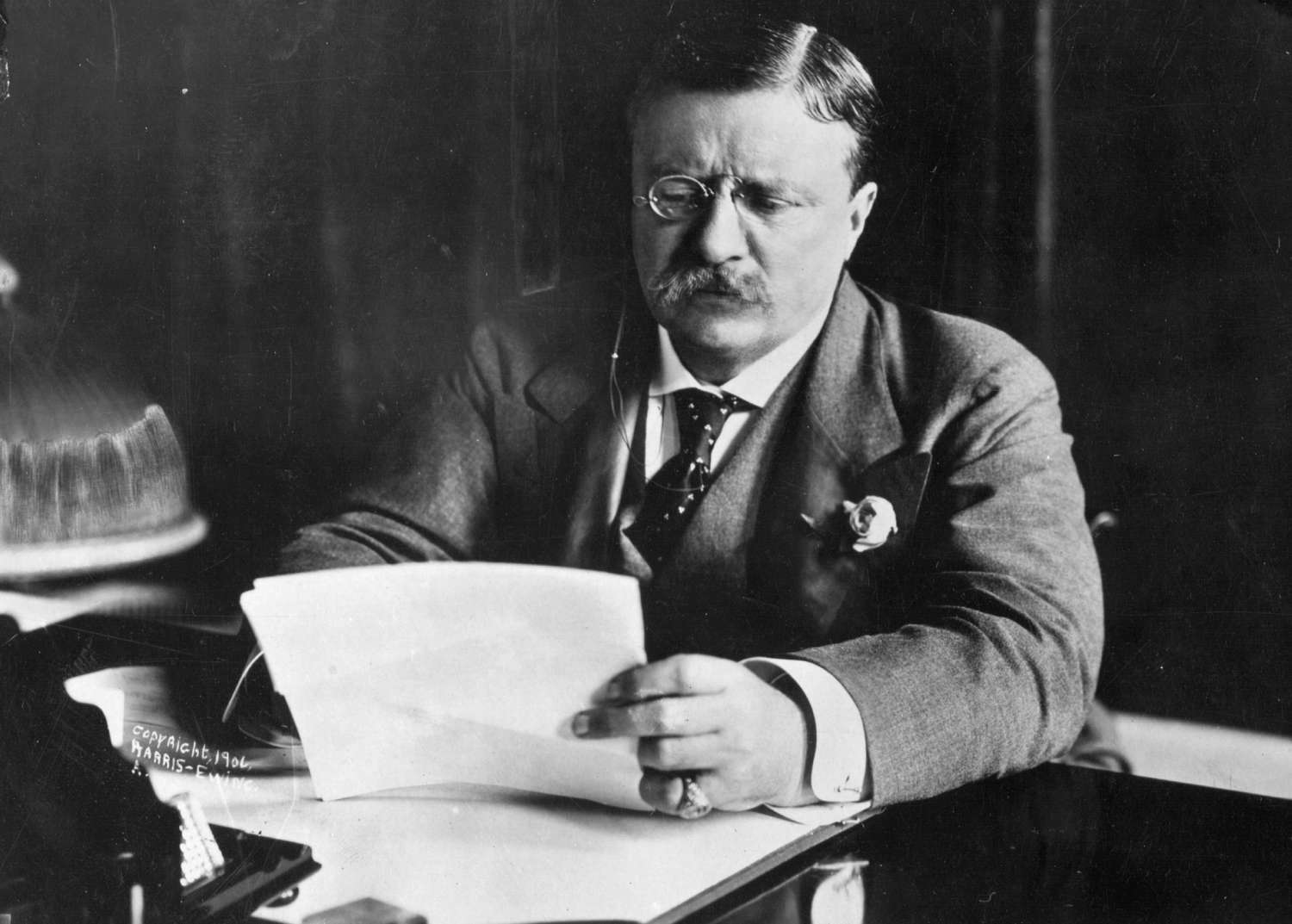

The Man Who Refused to Be Ordinary

He was the boy who couldn’t breathe — and the man who refused to stop running.

Before there were planes, before there were phones, there was Theodore Roosevelt.

Born weak, sickly, and small, he would grow up to wrestle wild cattle, charge up battlefields, and walk into the White House as if destiny itself had opened the door for him.

They called him The American Lion.

He didn’t just lead a country. He reshaped what it meant to be one.

But how did a frail boy from New York become the roaring face of the American century?

And what price did he pay for it?

A Sick Child, A Fierce Father

In 1858, New York was a city of smoke and steel.

Inside a brownstone on East 20th Street, a boy gasped for air.

His lungs betrayed him daily; asthma made every breath a battle.

His father, Theodore Sr., was everything the boy was not: tall, strong, full of life.

One night, as his son wheezed again, he leaned down and said,

“You must make your body.”

That sentence would shape the rest of Theodore Roosevelt’s life.

From that day, the boy trained like his life depended on it — because it did.

He lifted weights, hiked mountains, boxed, swam in freezing rivers.

He made his weakness his fuel.

By the time he entered Harvard, the sick child had turned himself into a force of nature.

The Fire That Changed Everything

At 23, Theodore Roosevelt was already in politics — and already different.

While others chased wealth, he chased ideals.

He married Alice Hathaway Lee, his college sweetheart, and called her “sunlight itself.”

But in February 1884, sunlight turned to darkness.

His mother died in the morning. His wife died that same afternoon.

Both in the same house. Both in his arms.

In his diary, he wrote one line:

“The light has gone out of my life.”

He vanished.

Left New York. Left politics. Left everything.

He rode west to the Dakotas, where the sky stretched forever and men lived by grit alone.

He became a cowboy, a rancher, a hunter — and, slowly, himself again.

The West gave him what grief had taken away: strength, silence, purpose.

Years later, he would say,

“I never would have been President if it had not been for my experiences in North Dakota.”

From Cowboy to Commander

By 1898, America was changing — restless, industrial, ambitious.

And so was Roosevelt.

He returned to politics like a man on fire: reforming police corruption, taking on corporate monopolies, and speaking with a ferocity few could match.

When war broke out in Cuba, he didn’t send soldiers — he became one.

He resigned from his comfortable Navy post and volunteered to fight.

He led a group of scrappy volunteers — cowboys, miners, adventurers — known as The Rough Riders.

And on July 1st, 1898, in the heat of San Juan Hill, he charged.

Bullets flew. Horses screamed. Men fell.

But Roosevelt kept going, waving his sword, shouting orders.

When the smoke cleared, the Rough Riders had taken the hill — and Roosevelt had taken America’s heart.

He came home a hero.

Within months, he was Governor of New York.

A year later, Vice President.

And in 1901 — after the tragic death of President McKinley — Theodore Roosevelt became the youngest President in U.S. history.

He was 42 years old.

The President Who Wouldn’t Sit Still

From the moment he entered the White House, everything changed.

The place came alive — literally.

His six children turned it into a zoo: ponies in elevators, snowball fights in the East Room, even a pet badger named Josiah.

Roosevelt joined the chaos, laughing louder than any of them.

But behind that laughter, he was rewriting the presidency.

He wasn’t content to be a figurehead — he wanted to be a force.

He took on the nation’s richest men, calling them “malefactors of great wealth.”

He broke up monopolies, reined in the railroads, and gave workers their first fair shot in decades.

He called it the Square Deal — fair treatment for every American, rich or poor.

Then came the forests.

Most presidents saw trees as timber. Roosevelt saw them as tomorrow.

He preserved 230 million acres of wilderness — the birth of America’s national parks.

“Leave it better than you found it,” he said.

A simple creed that would echo for generations.

And he didn’t stop there.

He sent the U.S. Navy — gleaming white and unstoppable — around the world,

built the Panama Canal against impossible odds,

and turned America into a global power.

“Speak softly and carry a big stick,” he said.

And the world listened.

The Fall of the Lion

After nearly eight years in power, Roosevelt did something unthinkable.

He walked away.

“I can do more outside the White House than inside,” he told reporters.

He went on safari in Africa — hunting, writing, living large.

But Washington never stopped calling.

When his successor, William Taft, disappointed him, Roosevelt roared back into politics — this time under a new banner: The Bull Moose Party.

He championed women’s rights, fair wages, child labor laws — ideas decades ahead of their time.

The crowds loved him.

The establishment didn’t.

He lost. But he didn’t fade.

Even in defeat, he remained the most popular man in America.

And when the world plunged into war, he wanted to fight again.

At 58, nearly blind in one eye, he begged to lead troops in Europe.

The President refused.

So his sons went instead.

All four enlisted.

When his youngest, Quentin, was killed in combat, something inside Roosevelt broke.

For the first time, the man who had taught the world to charge forward sat still.

“Poor Queniken,” he whispered.

The roar had become a whisper.

The Last Night

On January 5th, 1919, Theodore Roosevelt told his wife Edith he wasn’t feeling well.

He went to bed early.

Sometime during the night, the man who had lived five lifetimes simply stopped breathing.

He was 60.

His son sent a telegram from France.

It read:

“The old lion is dead.”

But America didn’t mourn a lion.

It mourned the spirit of a man who had dared to be more than ordinary — and had made his entire country believe it could be too.

Today, we live in the century Roosevelt built — a century of ambition, reform, and restless energy.

He left behind national parks, fair labor laws, a stronger presidency, and a vision of America as a nation that acts.

He believed courage wasn’t about the absence of fear,

but about showing up, again and again, even when you’re broken.

As he once wrote,

“The joy of living is his who has the heart to demand it.”

Theodore Roosevelt demanded it — and in doing so, he gave an entire nation permission to do the same.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load