Before we open one of the most unsettling entries in Louisiana’s plantation records, take a second to ground us in the present. Drop a comment telling us where you’re watching from and what time it is. We’re mapping how far these buried histories travel—and when people choose to face chapters that were kept out of view for generations.

What follows is not a jump-scare ghost tale. It’s a story about memory, ledgers, witnesses, and a name that keeps resurfacing across archives and oral histories: Deline. The documents say she entered the record as Lot 29 at the St. Charles Exchange in New Orleans during the spring auction of 1854. The testimony that grew around her, though, touches something larger—an “accounting” that appears in diaries, marginal notes, and the echoes of what communities carried forward. Here’s how the record unfolds, what witnesses say they saw, and how that history refuses to disappear.

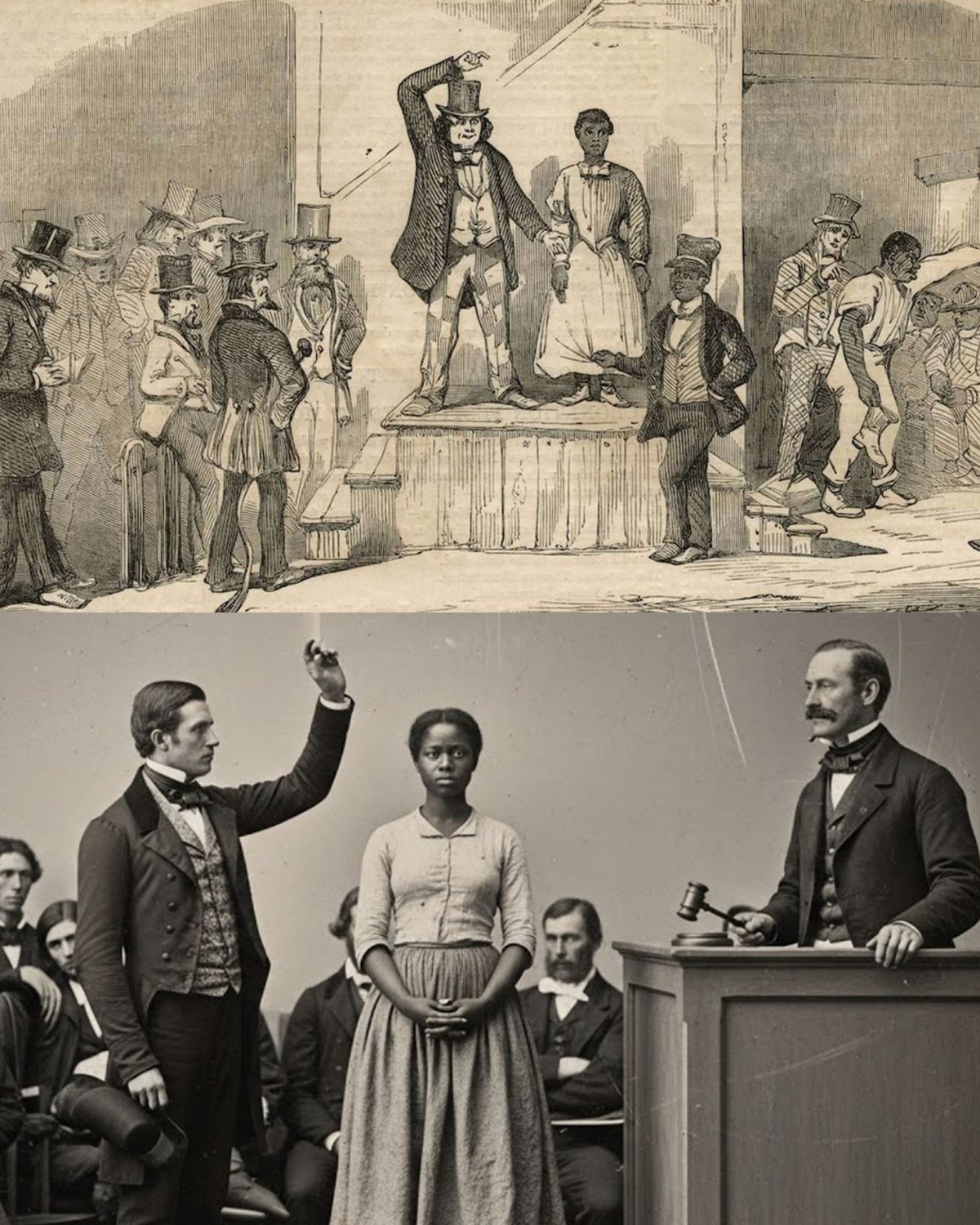

There are days when the weather changes a city’s mood. The morning of the spring auction at the St. Charles Exchange was humid enough to pull conversation down to a hush, but that’s not what quieted the room. The notary—meticulous, by all accounts—later wrote a line that still feels like a finger pressed to the page: “At precisely 10:47 a.m., Lot 29 entered the platform.” The name on the bill of sale reads: Deline. Age estimated 22. Height listed as tall for her era. Skilled in domestic work, needlework, and kitchen duties. Provenance through three estates.

Those in the hall disagreed on many things, but many remembered the moment she stepped into the light streaming through the Exchange’s tall windows. Conversations stopped. Even the auctioneer, Claude Forier—a man with three decades behind the gavel—seemed unusually cautious. He opened at a price that, for the time, implied a problem in the file. Silence met him. Paddles stayed down.

Then James Laveau arrived—a merchant’s son with money from cotton trading, eager to convert new wealth into old social standing. He’d purchased Bellamont Plantation three years earlier, a large estate upriver. He came late, saw Lot 29, and bid high without hesitating, cutting through the room’s reluctance. “One thousand dollars, in gold.”

A veteran planter, Etienne Deveau, rose with a warning: “I advise caution. Three prior owners—men with standing—died recently under troubling circumstances.” He didn’t narrate graphic details, and the official documents he referenced do not list wrongdoing. But the tone of his caution—steady, measured—landed like a stone on the floorboards.

James answered with the confidence of a man unaccustomed to reversing course in public. “If there are issues, they should be disclosed. I see none.” The gavel fell. The sale concluded. And in the notary’s careful script, a slim marginal line appeared next to the record: Buyer was warned by E. Deveau and others present. Proceeded despite unanimous counsel to decline. This notation is made for the record should future inquiry become necessary.

The journey upriver in Laveau’s carriage set the next scene: James inside; Deline seated beside the driver, Moses, on the exterior bench under an afternoon sun. Moses would later report simple answers to simple questions—yes, she could read and write; yes, she had managed a household; and to a final question, a sentence he carried for years: “Sometimes the universe keeps its own accounts, and some debts can only be settled in full.”

Bellamont appeared toward sunset, its Greek Revival facade bright against the trees. On the veranda, James’s wife, Marguerite, watched the carriage roll in. She saw Deline step down and gripped the railing as if something had shifted in the house before a foot crossed the threshold. In older letters you sometimes find sentences that feel like the beginning of a long cause: “I do not want her in this house,” Marguerite said. James, stung by public challenge, refused to yield. Deline would be assigned to Marguerite’s service and the management of personal rooms.

Within days, small things gathered into a pattern: candles flickering without a draft, a pot that simmered steady boiling over for no reason Celeste could name, and the feeling among the domestic staff that a quiet pressure had entered the house. Celeste—who had managed Bellamont’s domestic order for more than a decade—kept a diary that would later be found during a demolition. In one of her first entries after Deline’s arrival, she wrote, “When she looked at me, it felt as though every hidden thought had been read.”

Marguerite’s unease deepened. Food lost taste. Sleep slipped away. The mirror felt untrustworthy. She told James she felt watched, even when she stood alone. She described the sensation of cold when Deline adjusted her hair or fastened a dress—cold not as temperature, but as presence. James tried the reasonable path: a physician, rest, quiet. Marguerite’s response felt like an alarm bell: “You think it’s fascination, but it isn’t. It’s a hook.”

Days later, Marguerite was found at the base of the main staircase. The official conclusion recorded an accidental fall. Celeste’s diary suggests she witnessed a quiet exchange at the landing, a step backward, and a small gesture she could not explain. In the margins of memory, a sentence stayed with her: “One account settled. The balance shifts,” Celeste wrote that Deline whispered as she passed.

James wore the role of grieving husband without missing a social step. But those who watched him closely saw his attention moving toward the person at the back of the service—a tall woman with a still gaze who now directed the rhythms of the house.

Bellamont, like many estates of its era, lived on routine. Schedules are how large houses work. But routine began to fracture in ways that don’t read like a haunting so much as a reallocation of authority. Deline, now a free woman by notarized papers James signed in New Orleans, continued to live at Bellamont and, increasingly, to make decisions with James’s approval: menus, schedules, staffing, expenditures. The overseer—long feared by those assigned to the fields—was dismissed with one hour to pack. In that moment, several witnesses recall Deline watching from the veranda with a look not of gloating, but of conclusion. “Five names left,” one person heard her murmur. “The reckoning continues.”

By then, James’s study had transformed. The walls filled with papers: bills of sale, property records, plantation inventories, burial notes, and maps showing routes along rivers and roads where human beings had been bought and transported. At the center sat a ledger—a durable, leather-bound volume—and day by day, line by line, James copied names, dates, transactions. In Celeste’s account, his explanation was simple and startling: “Actions echo across generations. I am listing every name touched by this estate.”

Night walks began—sometimes with Deline at his side, sometimes alone—toward the small cemetery at the north edge where previous owners had buried the enslaved whose names were recorded in ledgers, and those whose names were not. Lanterns burned there at hours when most houses sleep. What he was doing in the dark was never fully documented; what he believed he was doing made it into Celeste’s diary: “Making a list… Everyone who profited from misery… The accounting must be complete.”

The household staff—those who remained—noticed another change outside the main house. Where work had been extracted under threat, it continued without the overseer’s presence for a different purpose. Under Deline’s direction, plants were planted in specific patterns. Gatherers moved through the swamplands to collect particular herbs. People were asked to dig at precise points to unearth small bundles of cloth containing hair, bones, dried herbs—objects that those who knew old practices recognized as conjure work. “She’s gathering it all,” said Ruth, an elder whose family roots traced to Haiti. “Old knowledge. Hidden power. It was buried to protect it. She knows how to hear it.”

Stories in the surrounding community found their way to front doors. Deliveries arrived to hollow-eyed acceptance. Social invitations went unanswered. On a holiday that usually drew the entire district, James did not appear. Deveau—the same man who warned him at the Exchange—rode to Bellamont, found the house cold despite summer heat, the shutters closed at noon, and James in a darkened study.

The exchange that followed reads like the pivot of a man’s worldview. “Position,” James said, “society—illusions. The bill has come due.” When Deline entered the room and placed a hand on his shoulder, Deveau later described a sensation that felt like both relief and pain on James’s face. “My master requires rest,” was the part of her sentence Deveau recorded. The other part stayed with him longer: “You have much to reflect upon regarding your own accounts.”

The community’s unease hardened into fear after a confrontation many would later recall as a hinge. A neighboring planter, known for cruelty that even in that era drew criticism, arrived uninvited and demanded James. Deline answered the door. Words were exchanged—words referencing a local incident of abuse that people had tried not to speak aloud. Anger rose. Moments later, the visitor collapsed in the entry. The doctor’s official record noted a sudden medical event. In private notes that surfaced decades later, he wrote of heart tissue that looked “extraordinary” for natural causes. Whether you read this as folklore or as testimony, one thing is clear: from that day, the region treated Bellamont as a place where the usual rules did not hold.

In July, a line appears in the diary that drew researchers back again and again: “He has become more than himself,” Celeste wrote. “When he speaks, the words are his, but the knowledge behind them feels old.” James told her he had counted: names purchased and worked; lives shortened by deprivation; children born on the property and sold away before anyone could inscribe them in the inventory. “The true accounting is beyond calculation,” he said. “But she knows.”

Efforts to intervene met a wall. The physician who had treated the family was turned away at the door, confronted not with melodrama but with a notebook and a list of names associated with his own purchases—documents that put him on his heels. He left without entering the house. His later fate, recorded quietly, became part of the region’s whispered calculus: there are ledgers beyond ledgers, and perhaps the most difficult pages are the ones we write ourselves.

By mid-August 1854, Bellamont’s routines had been inverted. The overseer was gone. Field hands worked not under threat but to fulfill tasks whose purpose they recognized from traditions their grandparents had guarded. The main house became a study hall for memory. The walls held maps—routes of ships, roads, and families separated across state lines; lists of buyers and sellers; and genealogies that stitched together fragments into lives. The ledger thickened with lines written at a steady pace that made sleep irrelevant.

On August 18th, James emerged from the study and gathered those who remained in front of the veranda. His appearance startled people—thinner, paler, moving carefully—but his voice cut through the heat with clarity. “I have completed the accounting,” he said. “Every name, every transaction, every life touched by this house and others like it.”

He turned to Deline, who stood beside him. “I understand why you chose me. Not because I was the worst—others were worse—but because I could be awakened. Because when confronted with the true cost of my comfort, I could not turn away.” His description of himself—“the instrument of my own judgment”—sounded less like a sentence and more like a decision to face what he had avoided.

Witnesses reported small fires that evening at specific points on the property—controlled, purposeful. The scent that rose from them triggered recognition in those who carried older knowledge. The word many used was summoning—a calling across a barrier. In the study, James made the final entry. And at the bottom of that last page, he wrote his own name and signed it, as if a ledger that started as inventory had become confession.

What happens at midnight depends on whose account you read. Diaries, statements, and later oral histories align on several elements: a cold, blue-white light in every window all at once; singing that seemed to come from no single voice; figures moving through rooms without the mechanics of doors or hinges; faces not vague like shadows but detailed enough for people to insist, years later, that they had recognized them from photographs and papers.

“The accounting is complete,” witnesses recall Deline saying in a voice that carried past plaster and wood into the open air. “Now comes the collection.”

James did not deny, deflect, or run. He walked to the center of the room where the ledger lay open and stood as if waiting for a verdict he already knew. The testimonies agree on that choice even as they diverge on the next description. Some said he “dissolved like smoke,” a phrase repeated because no one found better words. Others said he was “taken into the crowd” as if memory itself folded him in. Either way, when the light vanished and silence returned, the house stood empty. Deline was not there. James was not there. The ledger remained on the desk.

In the days that followed, the region collected stories the way a river gathers tributaries. A judge known for profiting from sales fell into a silence that lasted years. A planter in another state woke speaking a language his family did not know, identifying himself as a woman whose fate he described in detail before records confirmed her existence. A dealer disappeared into a river without a note; his account books were found on the bank filled with names written in handwriting no one in his family recognized. Official explanations varied—from illness to breakdown to flight. The folklore said something else: once the accounting began, it spread.

The state’s response to James’s disappearance stayed at a distance. The record lists departure for unknown parts, debts to be settled through auction, assets to be divided. No one wanted to live in the main house. People felt watched there, even at noon.

Bellamont’s main house stood empty for decades. People hired to clean or repair it reported a feeling that’s hard to put on paper: a presence when no one else was around; the smell of tobacco smoke when no one lit a pipe; the sense that a tall, quiet figure passed in the hallway just beyond the angle of vision. In 1891, the house burned. It started simultaneously in several rooms on a night with no lightning and no open flames. By morning, chimney and stones remained. The crew that responded heard singing—a detail that some repeated and others refused to discuss.

Time reclaimed the foundation. Trees pushed through floorboards. Vines wrapped stone. Fields where people had once labored became wetlands. Yet the land didn’t forget. Hunters saw a woman at dusk who vanished when approached. Travelers said their horses refused to pass a certain point for no practical reason they could find. People found small bundles in the brush—cloth, herbs, hair, bone—arranged in ways that matched older traditions for protection and memory.

In 1923, a university survey team arrived to document old plantation sites. At Bellamont, they uncovered something no property map had listed: a stone chamber beneath the main house, constructed from materials not native to the area. Inside, they found hundreds of small clay vessels, each sealed with wax and marked with symbols that scholars later linked to West African traditions—Yoruba, Igbo, Ashanti, and others. When carefully opened under controlled conditions, the vessels held soil—labeled in multiple languages with names and dates. The team lead wrote a report that administrators marked as restricted access; it was made public decades later. His conclusion read like someone laying out a pattern that defies simple explanation: a systematic collection of soils from unmarked graves of enslaved Africans across the region, spanning two centuries. At the center of the chamber, a sealed jar marked “Deline.” Inside, not soil but a ledger similar to James’s—except its entries continued long after 1854. The last line: “The accounting continues.”

The objects were reinterred according to the protocols of the day. The area was designated protected wetlands. The official write-up avoided speculation. Those who read the full field notes felt like they had been given back a library they didn’t know existed.

In 1967, on the anniversary of the August event, people arrived without invitation. No flyers, no phone tree—just a sense that they needed to stand where the house had been. The number grew to more than a thousand—Black and white, young and old—quiet in the dark. At midnight, people reported hearing singing. No one claimed the sound as their own. It felt like being welcomed and warned at once, like standing in a line that stretched through time. An organizer whose family traced back to Bellamont said she saw a tall, beautiful Black woman where the great room would have stood. The woman looked over the gathering with eyes that felt older than the century, then smiled—not with satisfaction, but with encouragement—and vanished like mist.

The site became a place people visited to leave flowers and names written on paper. In 2004, a historical marker was installed that used cautious language: a plantation once stood here; many enslaved people lived and died here; names and stories are missing from the record. Those who knew the deeper story understood the line beneath the plaque’s careful phrasing: the names were recorded somewhere. They had been kept.

The last public account surfaced in 2019, written by a descendant of a man whose name appears in testimonies tied to Bellamont. He went to the site, stood among the trees, and tried to find words to meet the past honestly. He wrote that he felt a presence, turned, and saw a tall woman with dark, steady eyes. She didn’t speak, but he understood something without hearing it: acknowledgement is a beginning, not an end; repair is work, not a gesture; forgiveness is not automatically owed. She faded. He stood alone, lighter—he said—not because he had been absolved, but because he finally understood what he was carrying and that the only way through was to contribute to the repair.

The Louisiana Historical Society received an anonymous donation in 1954—exactly a century after the auction that began this story. A small collection: a daguerreotype dated 1853 of a crowded sale, and in the background, a tall woman watching with a look that a curator later described as “patient calculation.” On the back, in handwriting consistent with ledger entries attributed to James, a single line: “She was there before. She is here now. She will be thereafter.” Below that: “Memory never dies, and neither does justice.”

Scholars remain cautious, as they should. They separate documents from folklore, testimony from embellishment. But if you spend long enough with the papers—the diaries, the marginal notes, the bills of sale—you see how stories travel in the South: through rooms, across fields, around tables. A historian late in a state archive once looked up from a stack of ledgers and saw a tall woman at the far end of the reading room, running her fingers along spines as if searching for a misplaced volume. The historian looked up to ask if she needed help and met eyes that felt like they held centuries. The woman smiled and said in a calm voice, “Keep reading. Keep writing. Keep remembering.” Then she was gone. The next page of the historian’s notebook held names no one had recorded—a list she insisted she had not written.

Skeptics point to the mind’s capacity to create meaning. Believers point to the way names keep resurfacing. Either way, the instruction is the same: keep the record. Bear witness. Refuse convenient lies. Insist on the dignity of people whose lives were reduced to inventory lines. The reason this story returns isn’t its supernatural edges, dramatic as they are. It’s the ledger—the idea that accounts exist beyond any one lifetime, and that justice, delayed or obstructed, still seeks balance.

The ledger attributed to James has never been officially recovered. Rumors say it appears when it needs to, that names are added in multiple hands, that it lands on the desks of people in power who have forgotten the human cost of their systems and need reminding. Maybe that’s a story people tell to feel less helpless. Maybe it’s a way for memory to do work.

Here’s what can be documented without reaching past what the paper will hold:

– A notary’s marginal note describing a public warning and a purchase made anyway.

– A household manager’s diary charting a house’s internal weather and the transformation of a man from certainty to accountability.

– An archive of transactions that, viewed as a whole, describe the extracted lives of hundreds of human beings, most of whom did not live to old age.

– A field report describing a chamber of clay vessels labeled with West African symbols and containing soils from unmarked graves.

– A pattern of dates, gatherings, and oral histories that point to a community’s need to mark, name, and be named.

And here is what the testimonies add, careful to attribute:

– A woman named Deline who entered the record as property and left it as something else: memory, judgment, or a presence people call by different names.

– A man named James who moved from possession to confession and signed his own name at the bottom of the final page.

– A sentence spoken in various places and times: “The accounting continues.”

What should we do with a story like this? If you’re a researcher, you keep reading. If you’re a teacher, you bring these documents into rooms where students can argue with them, weigh them, and learn their weight. If you’re a descendant—of those exploited or those who profited—you tell the truth out loud. And if you make media, you publish carefully: attribute claims, avoid sensationalism, and honor dignity. That is how stories like this travel safely and do the work they were meant to do.

Below is a clean, platform-safe close you can place in your caption or end card:

– “These aren’t just eerie tales; they’re records—of people, transactions, and the conscience that follows. If this history matters to you, share it forward and save it for reference. And if you’ve heard versions of this story in your family, add your piece below. Memory builds when voices join.”

The last image to hold is simple: the fields are quiet now. Cypress and willow shade the ground where names were once numbers. But on certain nights when the moon is dark and the heat sits still, some visitors say they hear singing—languages that predate the maps, harmonies that refuse to be buried. Beneath the sound, like a heartbeat, the turning of pages. Accounts kept. Debts tallied. Not for punishment as spectacle, but for acknowledgment as a beginning. Because justice that starts in memory has a chance to land in action.

And in that sense—in the careful work of reading, writing, and remembering—the ledger is always open.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load