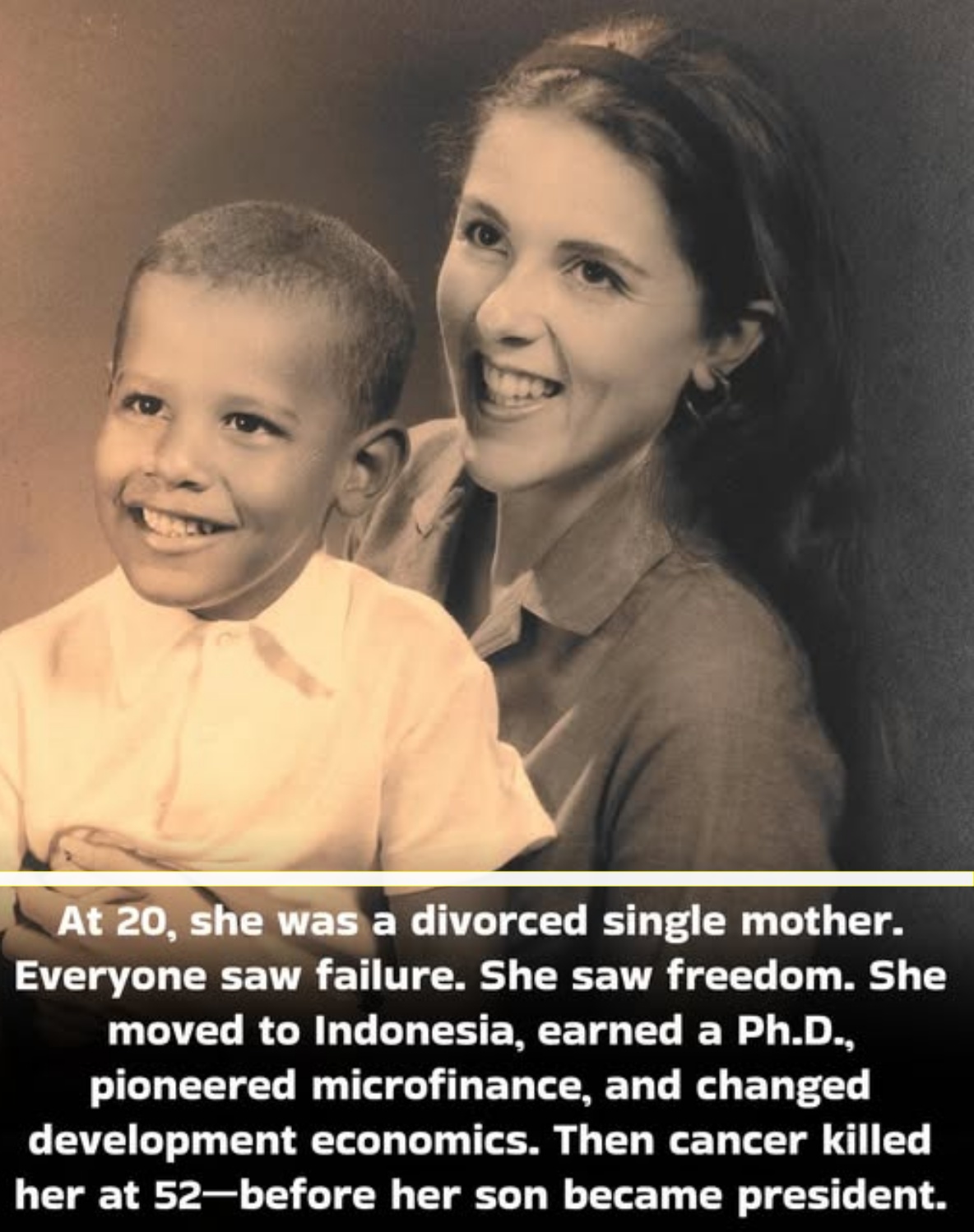

At 20, she was a divorced single mother in 1963 America.

Everyone saw failure. She saw freedom.

She moved to Indonesia with her six-year-old son, earned a Ph.D. studying rural blacksmiths, and pioneered microfinance programs that would lift millions out of poverty.

Then cancer killed her at 52—three years before her son became President of the United States.

This is Mercer Island, Washington, 1959. Stanley Ann Dunham—she went by Ann because “Stanley” was the name her father wanted for a son—was 17 years old and already the most unconventional girl in her high school.

While classmates worried about prom dates and fitting in, Ann was reading Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. She questioned everything: Why couldn’t women have the same opportunities as men? Why did racism exist? Why did people accept poverty as inevitable?

Her classmates called her “the original feminist”—decades before that became something you could be publicly.

At 18, she enrolled at the University of Hawaii. There, she met Barack Obama Sr.—a charismatic Kenyan graduate student with a sharp intellect and dreams of returning home to help build his newly independent nation.

They fell in love. They married—an interracial marriage in 1961, when that was still illegal in many U.S. states.

In August 1961, Ann gave birth to Barack Hussein Obama II.

The marriage lasted less than three years. Obama Sr. left for graduate school at Harvard, then returned to Kenya without his wife and son. Ann was 20 years old, divorced, with a biracial child, in an era when all of that carried crushing social stigma.

Most people would have gone home defeated. Lived quietly with her parents. Accepted that her life had been derailed.

Ann saw opportunity.

She continued her education at University of Hawaii while raising Barack, working as a waitress to pay bills. In 1965, she married Lolo Soetoro, an Indonesian graduate student. When he returned to Indonesia in 1967, Ann made a decision that shocked her family: she was going with him.

And she was taking six-year-old Barack.

Indonesia in 1967 wasn’t a tourist destination. It was a developing nation recovering from political violence that had killed hundreds of thousands. Most of the population lived in rural poverty. To American eyes, it looked like hardship.

To Ann Dunham, it looked fascinating.

While Barack attended local Indonesian schools, Ann began exploring villages outside Jakarta. She was particularly drawn to the blacksmiths—craftspeople creating intricate metalwork using techniques passed down for generations.

She noticed something Western development experts missed: these weren’t backward people who needed Western civilization imposed on them. They were skilled artisans with sophisticated traditional knowledge running complex small businesses.

Their poverty wasn’t from lack of intelligence or work ethic. It was from lack of access—to capital, fair markets, economic infrastructure.

This observation would become the foundation of her life’s work.

In 1971, Ann made another difficult decision: she sent ten-year-old Barack back to Hawaii to live with her parents and attend better schools. It broke her heart—but she believed his education was more important than keeping him close.

She stayed in Indonesia and dove deeper into her research.

Ann earned her master’s degree, then enrolled in a Ph.D. program in anthropology at University of Hawaii, conducting fieldwork in Indonesia that would span decades. Her dissertation—nearly 1,000 pages—was a comprehensive study of rural Indonesian blacksmithing and cottage industries.

But it was more than academic research. It was a fundamental challenge to how the Western world understood poverty.

The prevailing development theory in the 1970s was patronizing: poor people in developing countries were poor because of their “culture.” They were supposedly lazy, didn’t understand business, needed to adopt Western ways.

Ann’s research demolished this view. She documented that rural craftspeople were sophisticated business operators who understood their markets, managed complex production systems, supported extended family networks, and possessed deep technical knowledge.

They weren’t poor because they were backward. They were poor because systems excluded them—traditional banks wouldn’t lend to them because they were rural, poor, and often female. They couldn’t access fair markets. They lacked economic infrastructure.

Ann didn’t just write about this. She did something about it.

She began working with microfinance organizations—programs that provided small loans to people traditional banks ignored. We’re talking about loans as small as $50 or $100. Amounts that seem trivial to Western banks but that could allow a rural woman to buy materials, expand production, send her children to school.

These weren’t charity handouts. They were investments in people who’d been systematically excluded from economic opportunity.

Ann worked with Bank Rakyat Indonesia and USAID, helping design and refine microfinance programs. Her anthropological insights were crucial: she understood local culture, respected traditional knowledge, designed programs that worked with existing community structures rather than imposing foreign models.

The programs she helped develop in Indonesia became models that influenced microfinance worldwide. Today, microfinance has reached hundreds of millions of people, with women as primary beneficiaries and repayment rates often exceeding 95%—better than traditional bank loans.

While Ann wasn’t solely responsible for the global microfinance movement, her work provided crucial evidence and practical models that proved these programs could work.

Throughout this, Ann lived her values. She didn’t study poverty from comfortable hotels—she lived in villages, sometimes without electricity or running water. She raised her daughter Maya (from her marriage to Lolo) immersed in Indonesian culture. When Barack visited during college breaks, she made sure he understood the dignity and complexity of the communities she worked with.

Years later, President Obama would say his mother gave him his core values: that everyone deserves dignity and opportunity, that poverty is a systemic problem not a personal failing, that change comes from understanding people rather than imposing solutions.

In 1994, Ann was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. She continued working through treatment, finishing research projects, refusing to slow down.

She died on November 7, 1995, at 52 years old.

She didn’t live to see her son elected to the Senate in 2004. She never saw him become President in 2008. She didn’t witness the microfinance movement she helped pioneer spread globally or see Muhammad Yunus win the Nobel Peace Prize for work she’d contributed to decades earlier.

She died as she’d lived—working, researching, committed to equity.

For years, Ann Dunham was known primarily as “Barack Obama’s mother”—a footnote in her son’s historic story. News profiles during his campaigns focused on her briefly: the white woman from Kansas who married a Kenyan student, the absent mother who sent her son back to Hawaii.

These narratives missed who she actually was.

Ann Dunham was a groundbreaking economic anthropologist who earned a Ph.D. when few women did. She challenged fundamental assumptions about development that shaped international policy. She pioneered practical approaches to poverty alleviation that improved millions of lives.

She did this while navigating divorce, single motherhood, cultural displacement, and the countless obstacles placed before independent women in the 1960s-70s.

She was “the original feminist” who didn’t just talk about equality—she lived it. Who didn’t just study poverty—she worked alongside poor communities for decades. Who didn’t accept the world as it was—she documented how it could be different.

Her dissertation is still cited by development economists. The microfinance programs she helped design still operate. The approach she pioneered—respecting local knowledge, working with communities rather than imposing solutions, understanding that poverty is structural not cultural—is now standard in international development.

These ideas seem obvious now. In Ann Dunham’s time, they were revolutionary.

President Obama keeps a photograph of his mother in the Oval Office. In his memoir, he writes about her influence extensively. But even he acknowledges that for years, he didn’t fully understand the significance of her work.

She was just Mom—brilliant, unconventional, sometimes frustrating because she’d chosen research in Indonesia over staying with him in Hawaii.

Only later did he realize: she wasn’t abandoning him. She was showing him, through her life, what commitment to justice actually meant. That making the world more equitable required more than good intentions—it required deep understanding, sustained effort, and willingness to challenge comfortable assumptions.

Stanley Ann Dunham: November 29, 1942 – November 7, 1995.

Fifty-two years old. Too young.

She revolutionized how we think about poverty. She proved microfinance could work. She raised a president.

But her legacy isn’t just her famous son. It’s in the approach she modeled: Listen first. Respect local knowledge. Challenge your assumptions. Work with people, not on them.

She was the original feminist who lived in Indonesian villages. The divorced single mother who earned a Ph.D. The anthropologist who changed economics. The woman who saw opportunity where others saw failure.

And maybe—finally—it’s time we remember her for who she was, not just whose mother she happened to be.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load