In 1803, Lima was the jeweled heart of the Spanish Empire in South America — a city of gold and hypocrisy.

Its mansions glittered with chandeliers and imported mirrors from Cádiz, but beneath the marble floors were cellars filled with the enslaved.

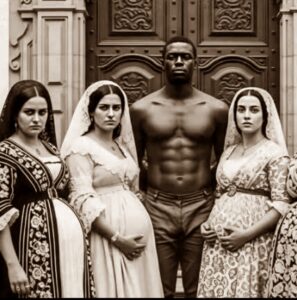

The Marchioness Catalina de Agüira Velasco was one of the most powerful women in Lima. Widowed young, she inherited vast estates, hundreds of servants, and a reputation for being untouchable. Her household was run with military precision, her daughters were raised under the watchful eye of nuns, and her name carried more influence than most governors.

To outsiders, her world was perfection — the frozen portrait of noble virtue.

But inside the Velasco mansion, beneath the polished surface of status and sanctity, lived the silent presence of those who made that illusion possible: the slaves.

Among them was Domigo, a man barely thirty, born in captivity yet known among servants for his intelligence and strange calm. He was trusted with the most intimate tasks — the tending of gardens, the maintenance of the family’s private chapel, and, occasionally, assisting the ladies of the house with errands that blurred the lines between service and presence.

No record tells us exactly how it began — only fragments pieced together from suppressed letters and testimonies smuggled into the archives of San Marcos University decades later.

One letter, written by a former maid, describes “a night of games” held during the Festival of San Ignacio — a masked celebration known for loosening the strict codes of class. Nobles danced beside servants, masks concealed rank, and laughter echoed through candlelight.

It was said that during this night, Domigo, wearing a simple ivory mask, was mistaken for a European guest. Or perhaps, some whispered, he wasn’t mistaken at all.

What happened in the hidden courtyards of the Velasco mansion that night remains unclear. But nine months later, the city would be in uproar.

By July 1803, the Marchioness and all three of her daughters were visibly pregnant. Servants spoke of morning sickness, doctors visited at odd hours, and every explanation — from “miraculous illness” to “divine punishment” — failed to calm the gossip.

Then came the discovery that ended all pretense.

One morning, as the midwife arrived, she found the women wearing identical masks — masks that matched one found in the slave quarters.

The masks were traced to Domigo.

The connection was undeniable.

The reaction was instant and ruthless.

Within hours, the Velasco mansion was surrounded by guards. Domigo was seized, dragged through the courtyard, and never seen again.

Officially, there was no record of his arrest or execution. The city archives list him as “missing property.” But in the private correspondence of the Viceroyal court, one chilling note survives:

“The man has been silenced. The honor of Spain will not be questioned.”

The Marchioness withdrew from public life, her daughters sent to convents “for recovery and repentance.”

Rumors spread like wildfire. Some claimed the Marchioness had fallen under witchcraft — that Domigo had bewitched her and her daughters with African charms. Others believed it was revenge: that generations of cruelty had found its echo in a single act of rebellion disguised as desire.

The Spanish crown’s colonial bureau, the Corvo Español, swiftly censored newspapers, confiscated portraits, and threatened imprisonment for anyone repeating the story.

Within months, the scandal was scrubbed from the official record.

Only whispers remained — passed down in servants’ tales, in confessional murmurs, and in the uneasy silence that hung over Lima’s aristocracy for decades.

For nearly two centuries, the “Lima Scandal” was dismissed as legend — a colonial ghost story.

Then, in 1978, Peruvian historian Dr. Isabel Muñoz uncovered a series of sealed letters in the National Archives. Among them was one written by Sister Inés de la Paz, a nun who had served in the Velasco household. The letter described Catalina’s “unholy sorrow” and spoke of a child born “with eyes too dark for a noble cradle.”

Dr. Muñoz’s findings reignited debate. Was it a love story? A crime? A rebellion wrapped in intimacy?

What no historian could deny was what it represented:

The terror of a society built on hierarchy, confronted by the one thing it couldn’t control — desire.

Domigo’s name, once erased, became a symbol in Afro-Peruvian art and literature. Murals appeared in Lima’s old quarters showing him not as a criminal, but as a mirror of a system’s hypocrisy.

The story is retold in whispers still — a haunting parable of power, silence, and the blurred lines between servitude and sovereignty.

History records the conquerors. It rarely records the conquered.

But every now and then, a story breaks through the marble of empire to remind us of what was buried beneath it.

The Lima Scandal of 1803 isn’t just about forbidden intimacy — it’s about how fear governs societies that claim to be moral.

The masks may have been burned, the bodies forgotten, but the questions they left behind still echo:

Who owns a body?

Who defines honor?

And who decides which truths deserve to survive?

As Dr. Muñoz once wrote:

“Perhaps the true crime of 1803 was not desire, but the arrogance of those who thought they could erase it.”

More than two centuries later, the story of the Marchioness and her slave still disturbs, still fascinates — not because it’s scandalous, but because it forces us to confront the one truth every empire fears most:

That the human heart has never recognized hierarchy.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load