For seven years, she couldn’t stand, couldn’t stretch, couldn’t speak.

Just inches below her — her children played, laughed, and asked where Mama had gone.

They never knew she was watching from the shadows.

They never knew she was right above them.

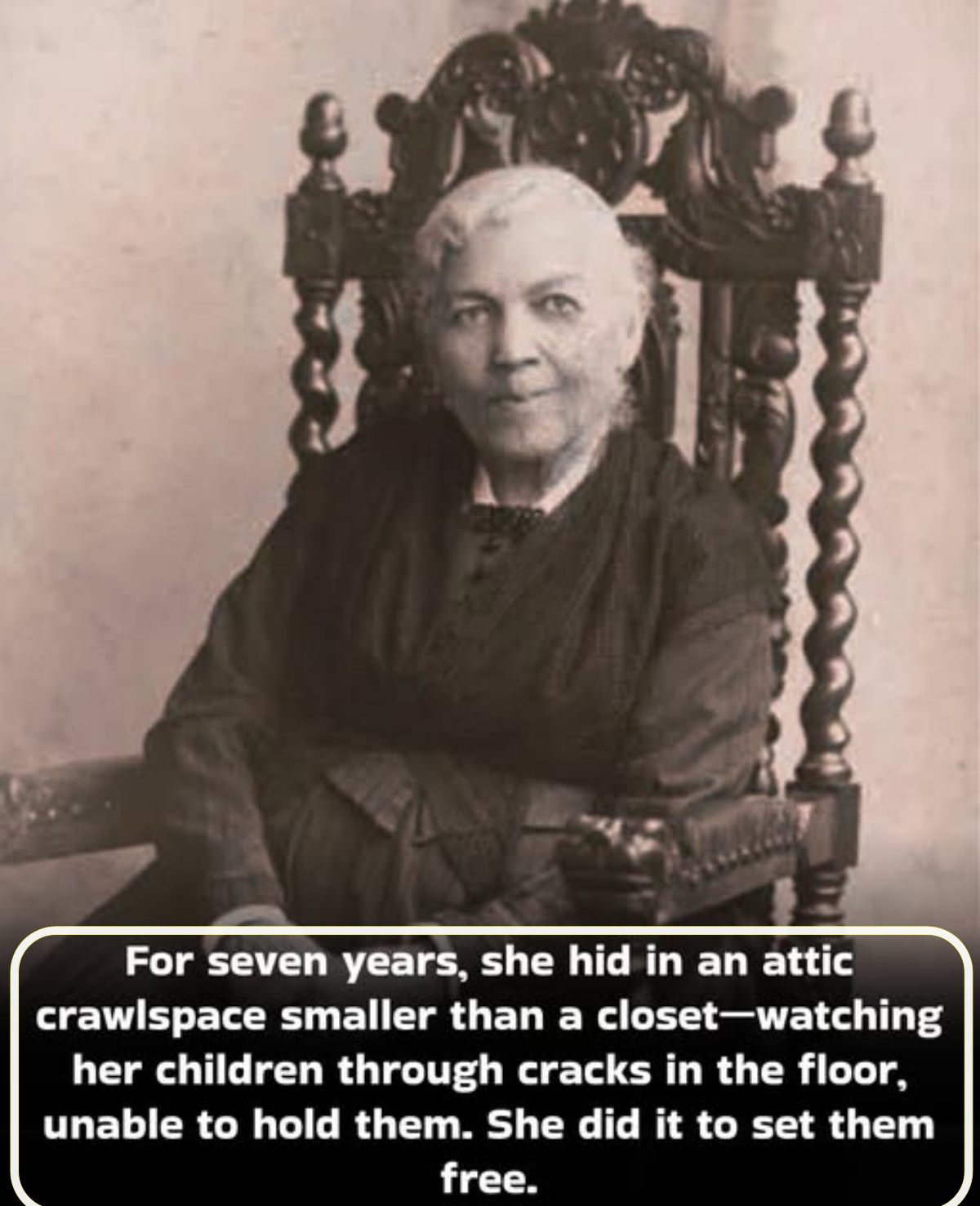

Her name was Harriet Jacobs, and what she endured to protect her children remains one of the most haunting acts of courage in American history.

Born enslaved. Hunted by her abuser. Forced into hiding in an attic no bigger than a coffin.

She didn’t run away to escape — she hid to fight.

Every day in darkness was one more day her children stayed free.

This is not just a story of slavery — it’s a story of survival, strategy, and a mother’s love strong enough to outlast terror itself.

Because sometimes, freedom isn’t loud.

Sometimes, it whispers through cracks in the floor.

Imagine a mother who can see her children, but they cannot see her.

She can hear their laughter, their crying, their footsteps. She watches them grow through splinters of wood — but she cannot touch them.

For seven years, Harriet Jacobs lived like that.

Hidden above her grandmother’s home in Edenton, North Carolina — in a crawlspace just nine feet long, seven feet wide, and barely three feet high — Harriet lay silent as the world moved on below her.

She wasn’t a fugitive from justice.

She was a fugitive from ownership.

And her only crime was refusing to let her enslaver destroy her children’s lives the way he had tried to destroy hers.

This is the true story of the woman who turned an attic into a battlefield — and motherhood into rebellion.

Harriet Jacobs was born in 1813 in a small coastal town, Edenton.

Her early childhood — miraculously — held moments of warmth. Her parents were literate, respected artisans. They shielded her from the full weight of slavery. For a few brief years, she didn’t know she was property.

That illusion shattered when she was six.

Her mother died. Her father soon after. And the child who once believed herself free was listed in a will — alongside furniture and livestock.

She was bequeathed.

To the daughter of Dr. James Norcom.

And Norcom, her new master, was a man whose obsession would define her existence.

Harriet was fifteen when Norcom’s attention turned from paternal to predatory.

He followed her. Whispered threats. Left notes. Promised comfort, then threatened violence.

For enslaved women, there was no law, no escape, no “no.” The system offered only cruelty — and silence.

Harriet understood something few dared to articulate: resistance could be fatal, submission unbearable. So she found a third path — survival through strategy.

To defy Norcom, she formed a relationship with Samuel Tredwell Sawyer, a white lawyer with power and influence.

It wasn’t love. It was leverage.

Two children were born of that decision — Joseph and Louisa. They became Harriet’s reason for living, and her greatest vulnerability.

Because Norcom’s rage only deepened.

When he couldn’t possess her, he vowed to destroy her — and to sell her children “to the highest bidder.”

For Harriet, the walls of the South had closed in. Escape seemed impossible. Until she found a hiding place that defied reason.

It was barely a crawlspace — the unfinished eaves above her grandmother’s home.

Nine feet long. Seven wide. Three feet high.

No windows. No insulation. Just planks and dust and the faint scent of pine.

To anyone else, it was a storage nook. To Harriet, it was sanctuary.

One stormy night in 1835, she climbed inside. Her grandmother sealed the entrance.

And for seven years, she never came out.

Days blurred into seasons.

Heat turned the space into an oven — suffocating, silent, unbearable. Her limbs stiffened, her skin blistered.

In winter, cold air seeped through the cracks and gnawed her bones.

But Harriet made a small hole in the floorboards — her window to the world. Through it, she could glimpse her children.

They thought she had escaped north.

They thought their mother was free.

She was only eight feet away.

Every hour was danger.

She couldn’t cough, couldn’t sneeze, couldn’t shift her weight too loudly. Norcom’s men searched relentlessly — dogs sniffing yards, neighbors whispering, rewards posted.

Harriet listened. Every footstep below her floorboards could mean discovery.

Yet she endured.

She wrote later:

“The continued hearing of my children’s voices was a great comfort to me. Yet it made my tears flow.”

Years passed. Her children grew. Her muscles atrophied. She developed sores that never healed. But her will — her impossible, iron will — stayed intact.

Each day she remained hidden, Norcom’s control weakened. He couldn’t find her. He couldn’t touch her. She’d stolen from him the one thing he could never reclaim: her autonomy.

Harriet’s attic became her rebellion — a place where silence screamed louder than protest.

In 1842, after seven years in confinement, Harriet made her move.

A network of abolitionists, both Black and white, orchestrated her escape. Hidden in cargo, carried by ship, she made it to Philadelphia — and then to New York.

For the first time, she breathed air without fear.

But even in freedom, Norcom’s reach haunted her. He placed ads. Hired hunters. Offered rewards.

So she lived under a new name. Worked as a nursemaid. Wrote letters in secret to check on her children.

Eventually, with the help of friends and allies, she reunited with them — finally holding in her arms the children she’d only seen through cracks in the floor.

It was a reunion seven years in the making.

And one the world would almost never know.

In 1861, under the pseudonym Linda Brent, Harriet Jacobs published Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

It was revolutionary — the first book to detail the sexual exploitation of enslaved women in their own voice.

Critics at first doubted it could be true. Its honesty was too raw, its pain too personal. But abolitionists confirmed her story.

Her words weren’t just testimony — they were indictment.

“Slavery is terrible for men; but it is far more terrible for women,” she wrote.

Harriet forced America to confront what it had refused to see: the hidden war waged against enslaved women’s bodies and souls.

Her courage turned trauma into truth — and truth into weapon.

After the Civil War, Harriet didn’t retreat into quiet freedom. She built schools for freed children. Fought for education, dignity, and healing.

She lived to see her grandchildren born into a world she had risked everything to imagine.

When she died in 1897 in Washington, D.C., she was a free woman — and an author whose voice would echo through centuries.

Her attic was torn down long ago. But the story remains: of a woman who endured darkness so her children could live in light.

She didn’t run from her pain — she weaponized it.

She didn’t escape to forget — she escaped to remember.

Harriet Jacobs didn’t just survive slavery.

She redefined resistance.

In a quiet house, children once played, and a mother lay hidden above them — praying they would never know the world that forced her into that space.

Today, when historians speak her name, they speak for every mother who chose silence over surrender, and every woman whose story was nearly erased.

Freedom, Harriet proved, doesn’t always roar.

Sometimes it whispers through wood,

watches through cracks,

and waits — patiently, painfully — for the day it can breathe again.

Her seven years in an attic became seven years of defiance — and one of the most profound love stories in American history.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load