At 2:47 p.m. on a gray Thursday in March 2024, Detective Amy Rodriguez watched a notification bloom at the top right corner of her monitor—the kind of bureaucratic toast that usually means another supplemental request or a password expiry. But the subject line stopped her hand above the mouse: CODIS Match Notification — Henderson, Sarah Michelle. Missing since: September 12, 1968. File last updated: 2019.

She leaned back against the wear-polished cushion of a state-issue chair, Springfield headquarters humming with fluorescent fatigue around her, the desk a chaotic survey of manila folders, coffee-ringed printouts, and the tidy savagery of post-its that multiply in long investigations. Eighteen years in the Illinois State Police, most of them fighting entropy in the cold case unit, had trained her to feel the gravity of a moment before facts assembled into meaning. This felt heavy. It felt irreversible.

The match should not have been possible—at least not in the language of the men who first boxed the evidence. In 1968, DNA lived in journals and labs, not in courtrooms. The double helix was a diagram, not a warrant. Yet the alert said what it said: a profile from biological material lifted off a torn blue cardigan—a sixteen-year-old’s sweater, bagged on a rural roadside outside Millbrook—now matched a known offender named Thomas James Carlisle. He had died in 2018. His profile had been added posthumously when Illinois widened its DNA collection rules in 2019. The sweater had been digitized in 2023, courtesy of a state cold case initiative that treated old evidence like seeds—dormant but viable, if you gave them the right conditions.

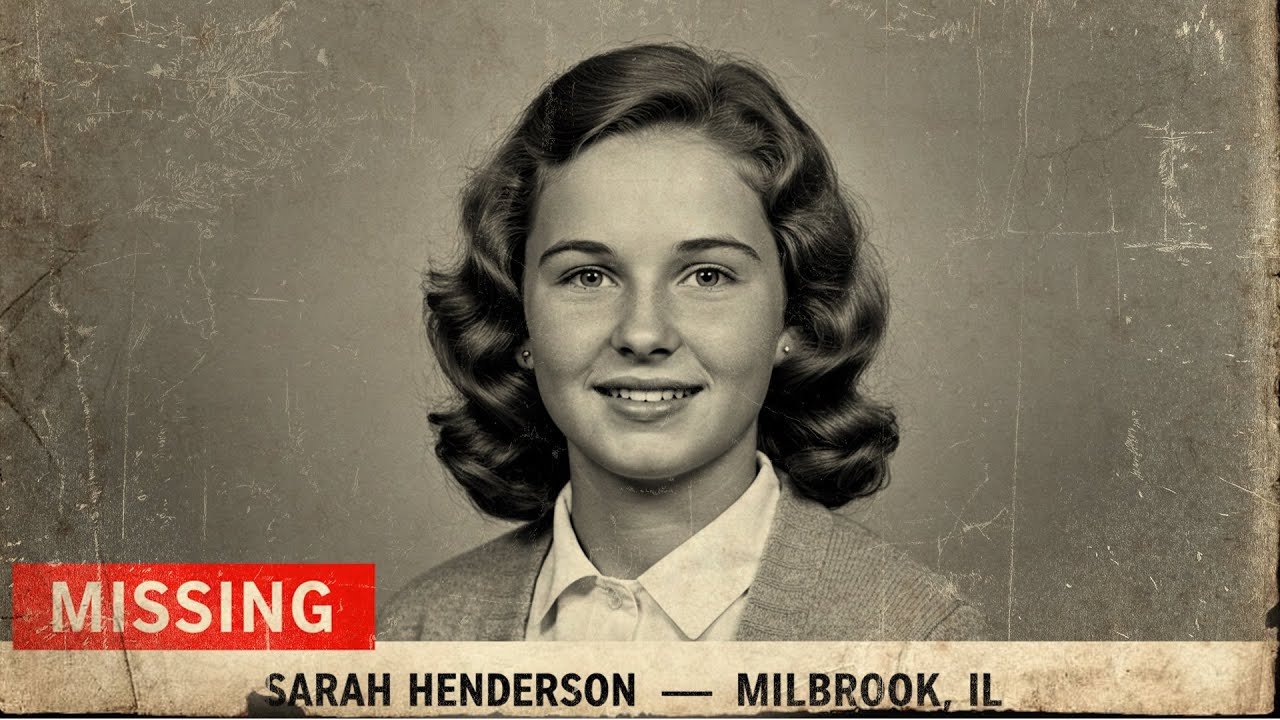

Rodriguez opened the file. A school portrait loaded in black-and-white increments—a young face, weeks shy of autumn, looking directly at a lens with the unobstructed confidence that small towns and good grades can instill. Sarah Henderson: junior at Millbrook High, daughter of Margaret and Robert, an honor roll kid whose routine was a metronome that ticked until it didn’t. She rode her Schwinn to school along a route she could do with her eyes closed. Somewhere between the farm and first period, the map folded.

If you were following this kind of thing from a distance, you might call what happened next miraculous. The people who had to write the memos would call it procedural. Here’s how a line in a database becomes a bridge over 56 years of doubt—and brings a family, a community, and a state to a point where paperwork finally says what everyone has felt in their bones.

I. September 12, 1968 — The Farm, the Road, the Pause at the Gate

If you live in Illinois long enough, September has a sound: crickets, combines, and the hush of summer’s last heat sitting on corn like a quilt. On Henderson Road—named less by the county than by habit—Margaret roused Sarah the way she had for three years straight of high school mornings, scrambled eggs done the way Sarah liked, bacon crisp but not brittle. Robert’s boots sounded against linoleum with the assurance of a man who had measured his days by sun and yield.

Details become artifacts when a life becomes evidence. Margaret would remember that Sarah seemed quieter than usual—thoughtful, distant, but not unhappy. The girl wore the blue cardigan she’d chosen for school pictures the week prior, layered over a white blouse. She had timed her route to Millbrook High: eighteen minutes door to door. She was punctual like that.

– The goodbye: 7:00 a.m., WLS’s grain report murmuring from the radio, Robert noting the time without meaning to, habit as witness.

– The image: a blue Schwinn Breeze rolling down the quarter-mile gravel driveway lined with oaks planted by Robert’s grandfather in 1923; a wave; a turn; a daughter framed by morning light and then gone from view.

– The routine: Henderson Road to Bramwell, southwest two miles, north on County Line 4—past the Morrison farm, the collapsing silo on the old Carlisle acreage, down into town where the grain elevator anchors the skyline like a civic metronome.

By 8:00 a.m., Mrs. Dobson marked Sarah absent in homeroom—a small act that would become a hinge. By second period, the office placed a call to the Hendersons’ farm. Margaret answered with flour on her hands, kneading bread because that’s what you do when lives move on schedule. The call broke the schedule.

At 11:47 a.m., Dale Morrison—whose property bordered Sarah’s route—found the bicycle lying on its side in tall grass near the County Line 4 intersection. The chain engaged. Tires fine. Basket neatly holding an algebra text, an English anthology, a spiral notebook with her cursive visible through wire mesh. Lunch bag present. Apple crisp. Nothing broken. Nothing spattered. The bicycle didn’t look like an accident. It looked like a pause.

Sheriff Douglas Walsh had been preparing for retirement, the kind earned by thirty-two years of rural law and order—property disputes, harvest-time scuffles, storm season rescues—but not missing children. He assembled what a county can assemble: three deputies, volunteer firefighters, civil defense. He marked grids drawn from a military memory. By midafternoon, sixty people walked corn walls eight feet high, calling Sarah’s name, voices threading with the rustle and the distant rumble of machinery.

Margaret joined the search against Walsh’s gentle advice, because of course she did. A mother’s voice calling for a daughter inside that landscape created a soundtrack people would carry with them for decades. The state police arrived by night with technicians and borrowed bloodhounds. The scent carried to where the bicycle lay; it evaporated at the intersection. On day three, the FBI installed a command post in the Millbrook firehouse. Telephone lines multiplied. Agent Richard Barnes, practiced in kidnappings that behaved differently in cities, organized across jurisdictions like a chess player. The search swelled to 300 volunteers. Farmers left harvest work to walk creek beds and woods. The Lutheran ladies organized food. The Morrisons kept coffee going from their kitchen like it was a sacrament.

– The inventory: tire tracks photographed, cigarette butts bagged, fabric scraps labeled, everything cataloged with the care of a man—Walsh—who understood that in an investigation like this, absence is a suspect.

– The fact: late September, nothing. October, the corn came down, fields went bare, the map yielded no trace. The file fattened. The hope thinned.

By winter, the investigation did what such investigations do inside agencies forced to triage—shifted from frantic and visible to deliberate and quiet. In 1968, quiet meant cold.

II. The Long Interval — A Family’s Ritual, a Town’s Memory, a File’s Migration

If you want to know what a cold case does to a family over years, watch a bedroom. At first, Sarah’s room remained a promise: the bed made each morning, ceramic horses dusted on the windowsill, algebra problems left open to page 47 as if continuing them could conjure a doorknob turning sometime after supper. Over time, preservation morphed into monument, then into something brittle and private. Robert, whose humor had once been the mortar of the household, moved to the guest room because the front of his shirt could not remain dry if he tried to pass that door at night. Margaret’s prayers became conversations; sometimes she wept in the middle of a sermon; sometimes she laughed at inopportune moments, lost in a memory only she could see.

Every September 12 for years, Margaret dressed carefully and drove to Sheriff Walsh’s office to file another missing person report that the law didn’t require but her heart did. Walsh received her with patience that outlasted his job. His successor, Sheriff James Miller, did the same. The reports grew baroque—connections to cases in three states, letters from psychics, private investigators who promised certainty for fees the Hendersons could not afford. The community kept its kindness and widened its distance. Margaret’s ritual confronted people with the truth small towns are not built to handle day after day: some stories don’t have returns.

Robert died in 1987, heart giving out in the barn. Everyone said what everyone says in these circumstances—that grief can be a pressure you cannot see but that can stop a clock as surely as any medical condition. Margaret lasted until 2019, a long goodbye in Sarah’s room, sleeping where the ceramic horses were, surrounding herself with timelines and pins and clippings and a map that tried to turn tragedy into a geometry someone might solve.

Meanwhile, the file did what files do. It moved between shelves. It endured a flood with only a watermark. In 1995, Detective Patricia O’Brien—conducting a basement inventory—found the box misfiled among civil records. Inside, evidence bag No. 7: the blue cardigan torn at the left shoulder seam; small envelopes labeled “unknown fibers” and “fabric fragments”; careful notes by FBI tech Robert Chen. In ’68, the fibers could only be described, not sequenced. By ’95, DNA was in courtrooms, but the instruments that could coax genetic truth from a scuffed sweater had only begun to be built. O’Brien documented, re-sealed, and marked the case like a note to the future: Wait for the science to arrive.

Michael Henderson—the little brother who had been eight in ’68—grew up in the shadow of a sister who had become less person than parable. When Margaret died, he inherited the command center her grief had built. He did what grief sometimes does when it is handed to someone who has learned to live with it: he organized. He digitized every letter and clipping, scanned every map, built a database from a life’s worth of perseveration. In this, he was his mother’s son, minus the torment’s habit of multiplying itself. He reached out to O’Brien, who had retired but kept the Henderson case active in the compartment of her mind where unsolved things rattle until treated. She had been waiting not for a miracle, but for a technique.

In 2023, after years of budget line items fought over in quiet conference rooms, Illinois green-lit a cold case initiative that did not make headlines but changed them: stabilize, digitize, extract. The state crime lab acquired new extraction kits designed for touch DNA and microtrace recovery on fabrics and fibers long presumed empty. Evidence bag No. 7 was logged, scanned, and—under a fume hood where time becomes a little less tyrannical—opened.

III. The Science That Arrived — DNA, Databases, and a Name With a History

Technicians work in sentences that courts can sit on. Doctor Jennifer Walsh (no relation to Sheriff Douglas) in the state lab treats narratives like a contaminant. The lab partitioned a sliver of the cardigan’s torn seam—fabric discreet enough to preserve the garment for future testing—and coaxed a profile from what clung to its threads. It wasn’t complete at first, but it was coherent enough to talk to CODIS. CODIS said nothing.

The lab pivoted to forensic genetic genealogy—an approach that demands rules, warrants, and restraint. With court authorization, the profile was uploaded to a public database used for ancestry research. The hit wasn’t a perp. That’s not how this works. It was a scattering of distant cousins whose family trees—when constructed backwards by a genealogist named Caroline Mitchell—branched into a stand of oaks in central Illinois in the 1800s and then converged in the twentieth century around a last name the original case file had recorded in a different context: Carlisle.

The list of living, age-appropriate male descendants in that branch was short: three men who would have been 18 to 35 in 1968 and within fifty miles of Millbrook. Two provided reference DNA and were excluded. The third was not available to swab. He had died in 2018. His name was Thomas James Carlisle—born 1946, Ford County. The lab compared the Henderson profile to Carlisle’s state sample—collected from a 2016 arrest for domestic violence and, under the post-2019 law, added to CODIS after his death. The match landed at the threshold that prefaces affidavits: extremely strong support for identity.

Rodriguez read. Then she read some more.

– The geography: In September ’68, Carlisle lived on his family’s property on Rural Route 7, less than three miles from the intersection where the Schwinn lay in the grass. The farmhouse sat back from the road, privacy as feature, not flaw.

– The record: A scatter of arrests and charges—minor thefts early; assaults and domestic violence later. Two arrests for what reports called “unwanted contact with minors,” both dismissed. The paper didn’t show a sex offender; it showed a man whose proximity to harm was frequent and whose consequences were intermittent. In a world without integrated databases, that can look like ambiguity.

– The file: He had been questioned briefly in October 1968, a name in a canvas. He said he’d been working on equipment that morning. A deputy saw nothing to seize on. The note was made. The line went quiet.

Bridges are built from more than one plank. Rodriguez called county courthouses, pulled microfilms, talked to detectives who kept their files like reliquaries. She found a folder in the basement of the son of Lieutenant Frank Kowalski, the original state police detective. Labeled “Similar Incidents — Unconfirmed Connection,” it contained notes Kowalski had made in the early 1970s about attacks on young women between Dewitt, McLean, Ford, and Champaign counties. The common denominators were uncomfortable: rural roads, evening hours, victims 15 to 19 with hair like Sarah’s. Kowalski had surveilled Carlisle informally at times, documented movements, felt the tug of a pattern he couldn’t make official in an era when jurisdictional walls were higher and tools were fewer. The notes did not convict. They contextualized.

Evidence, like grief, wants place. There was one place left that might answer without calculus: the property itself.

IV. The Ground Speaks — A Farm, a Search, a Box That Changed the Room

In December 2023, with the permission of Carlisle’s son, David—who had inherited the land and used it as a weekend hunting site—the state police executed a search with technology that 1968 couldn’t dream of: ground-penetrating radar, cadaver dogs trained to read what the soil exhales. The house had been demolished in 2020. The foundation remained. The dogs alerted near a corner of the old basement’s footprint. The radar returned a signal that said: disturb this.

Under a concrete slab, excavators uncovered a metal toolbox sealed against time as if time could be bargained with. Inside were objects investigators prefer to describe clinically and families recognize immediately: pieces of clothing; jewelry; small personal items that matched property lists from cases across counties and decades. Among them, a small ceramic horse—a palomino mare, cream and gold faded but intact—that appeared in 1968 photographs of Sarah’s bedroom windowsill. Margaret had described those horses in interviews, those glass-lit mornings lit in her memory. The match was not metaphysical. It was photographic. It was physical.

– The chain: Items were bagged, logged, photographed, their discovery location measured and mapped. The ceramic horse was cataloged against the original 1968 inventory photographs.

– The lab: DNA recovered from other items linked Carlisle to additional unsolved cases in the region between 1969 and 1987. The horse did not carry DNA. It didn’t need to. It carried provenance.

– The family: David Carlisle cooperated. He talked about growing up in a house where violence felt like weather—present, deniable, everywhere. He had suspected his father could be cruel; he had not imagined scale. He stood outside the search perimeter and looked at the horizon like it could answer back.

Back at headquarters, Rodriguez assembled a case that could no longer intersect a trial but that had to satisfy the rigor of one. The standard shifts when the defendant is dead; the discipline should not. She wrote the kind of report that reads like a sequence of knots: DNA match to cardigan; genealogical convergence; proximity and opportunity; recovered property; corroborating patterns; cross-jurisdictional confirmations. Eight cases closed on paper in January 2024 with statements from state’s attorneys that if alive, Thomas James Carlisle would have faced charges ranging from first-degree murder to aggravated kidnapping and beyond.

For Sarah’s file, the language was both simple and heavy: victim identified; offender identified (deceased); cause and manner established by forensic review of evidence and corroborating property; homicide.

Some truths arrive that way—through a chain of custody instead of a confession.

V. The Call, the Horse, the Room Where the Past Was Held

Michael Henderson was in his home office reviewing quarterly equipment sales on January 18, 2024, when the call came from Rodriguez. The date—fifty-five years and four months—was an accident. He would remember it like a design anyway, because human memory wants meaning the way bones want calcium.

Rodriguez spoke with the care of someone who knows words become architecture in a person’s head. She laid out the evidence; avoided speculation; offered the sentence that changes a family’s gravity: we can say with certainty what happened and who did it. She explained the ceramic horse, the chain of evidence, the corroborations from other cases. She did not dress truth in adjectives. She let it stand there in the room.

Relief and grief are not antonyms. They can occupy the same chair. Michael felt both, plus a third thing—anger sharpened by the knowledge that had 1968 possessed the tools and networks of 2024, other families might have been spared their own anniversaries. He did what a son does who has learned to metabolize anger into action: he asked to see the evidence.

In Springfield, in a conference room where countless briefings have washed over countless families, the ceramic horse sat on a white paper mat under neutral light. It was small, the kind of gift you buy for a fourteen-year-old because it looks like hope—glossy, delicate, arranged in a series on a sill so the morning sun can grant it movement. Michael recognized it instantly with the double-sensation that accompanies forgotten objects made present again, part memory, part muscle. He remembered the birthday; how Sarah had arranged the set just so; how she would have chided him for misplacing one if he had dared touch them. He held the mare in his hands and understood why objects outlive us: they store us.

The state issued formal closure notices. The community organized a service. Michael organized something else: purpose.

VI. The Service and the Foundation — What Closure Looks Like When You Refuse to Shrink It

On March 15, 2024—fifty-five and a half years from the day Sarah didn’t arrive where she was supposed to be—the Millbrook Lutheran Church filled with the people towns produce: classmates turned grandparents; farmers who had walked those grids in ’68; deputies who had carried boxes across decades; officers too young to remember but old enough to care. There were no television vans elbowing for position. This was not a spectacle. It was a correction.

Michael spoke plainly. He thanked the state police, the lab, Detective Rodriguez, Patricia O’Brien, the genealogist, the prosecutors who crafted declarations that let completeness exist without a sentencing hearing. He spoke of his mother with a gentleness that refused to turn her into a caricature of desperation. He named what grief had done to their family and what persistence had done back to grief. He announced the Sarah Henderson Foundation: a non-profit dedicated to supporting families of missing persons in rural communities, funding training for small departments on modern forensic techniques, and, critically, building inter-jurisdictional communication systems that treat county lines like administrative conveniences rather than investigative walls. The first grant, he promised, would pay for two things that sound boring and therefore are essential: a cold storage freezer for evidence and a shared case management system that lets detectives in neighboring counties see echoes instead of silos.

After, the town moved outdoors to a small marker in the Lutheran cemetery beside Robert and Margaret’s graves. The marker’s words were careful: Sarah Michelle Henderson, 1952–1968. Loved, Sought, Found. People said what people say in good communities—if you need anything; we’re so grateful; I remember when she taught my cousin’s kid to tie her shoes. The words mattered less than the standing there together did.

VII. Anatomy of a Solve — Why This Worked When So Many Don’t

Long reads like this can lazily attribute success to a hero or a twist. The Henderson case resists that urge. It closed because policy, science, and ordinary diligence synchronized.

– Preservation over nostalgia: Evidence bag No. 7 survived a misfile and a leak, because someone sealed it right and someone else logged it right, and a third someone—O’Brien—recognized that misfiled doesn’t mean useless. Climate control and chain-of-custody logs don’t make headlines; they make justice.

– Technology with guardrails: Forensic genetic genealogy is powerful because it is bounded. Illinois built legal pathways for its use that included judicial oversight and explicit constraints on scope. The lab did not “search a consumer database” casually; it pursued a court-approved investigative step with a specific victim and a specific aim, and it did so transparently.

– Interoperability as doctrine: The case crossed McLean, Ford, Dewitt, and Champaign counties. The 1970s lacked the systems to integrate pattern and place. The 2020s have no excuse. The foundation Michael launched will fund the kind of case-sharing and alerting that reduces “we didn’t know” to the rare exception.

– Narrative discipline: Rodriguez’s team avoided the dramaturgy that sometimes seduces cold case work. Where the evidence proved, they asserted. Where it suggested, they labeled. Where it could not speak, they didn’t put words in its mouth.

– Community patience: The town did not weaponize rumor against due process. David Carlisle, asked to let law enforcement dig up a family past most would prefer to pave over, consented. Communities often talk about “cooperating with police.” The reverse matters too: police cooperating with a community’s need for decency and clarity.

In short: the case solved because every small decision aligned with a single ethic—tell the truth carefully.

VIII. The Another Life of Evidence — Other Names, Other Files, Other Closures

The investigation into Carlisle’s probable other victims generated eight official closures by early 2024. For three, DNA provided definitive connections. For several more, recovered belongings spoke where bone could not. Prosecutors issued posthumous charging determinations—statements that carry less legal weight than indictments but far more moral and practical force than rumor. Families received letters that used careful words: concluded, determined, closed. Each letter represented more than a file moved from one cabinet to another. It represented years of birthdays and Christmas mornings haunted by an empty plate and chair that could finally be acknowledged without the compulsory “maybe.”

There were facts that complicated comfort. In November 1968, Lieutenant Kowalski had obtained a warrant to search Carlisle’s property based on truck sightings near County Line 4 the morning Sarah vanished. Administrative delay pushed execution by two weeks. By the time deputies arrived, anything Carlisle would have been reckless enough to leave above ground was gone. The warrant’s scope—reasonably narrow in 1968—didn’t authorize the kind of exploratory excavation that 2023’s technology would later justify. The ground secrets remained ground.

To read those memos in 2024 is to feel two things at once: anger at what might have been prevented, and humility about what people did with what they had. The lesson isn’t blame. It’s design. Build systems now so that the next 1968 does not become the next 2024.

IX. Ethics in the Main Aisle — Privacy, Power, and the Promise We Owe the Living

Any story that includes genetic genealogy should carry a paragraph with a seatbelt. DNA found on a victim’s clothing is not a character. It is a data point that can be misused if not hedged by law and culture. Illinois’s expansion of DNA inclusion in CODIS after 2019 was debated for a reason. Posthumous inclusion of offender profiles is a policy choice with civil liberties implications. Using public genealogy databases requires consent frameworks that are legible to the people who upload their data. The Henderson case adhered to those frameworks; courts approved the searches; the public interest was compelling; the lab scoped queries appropriately.

– Consent must be intelligible, not merely legal. People clicking “share” on ancestry platforms should have access to clear, non-alarmist explanations of potential law-enforcement use and opt-out mechanisms that are easy to find and honored in practice.

– Equity matters because data is not neutral. Communities under-represented in consumer DNA databases may benefit less from genealogical techniques. Communities over-represented in offender databases may face disproportionate exposure. Policy should address both realities with transparency and remedies.

– Guardrails should be path-dependent. Success should not loosen rules; it should tighten best practices. The power that solved Sarah’s case will be more legitimate—not less—if its conditions of use are made stricter by its own triumph.

Ethics, here, is not a side plot. It’s the binding of the book.

X. The Detective and the Desk — What Work Looks Like After the Applause

After the service, after the press release, after the conference room where the horse was returned to the light, Rodriguez returned to the fluorescent-soaked desk where the notification had first appeared. Another queue of files blinked in need of triage. State police work is an assembly of unspectacular labors punctuated by days like this one. She moved the Henderson folder from active to closed and created a cross-reference packet for the FOIA officer, because transparency scales justice. She filled out a training memo: Lessons from Henderson — Evidence Preservation, FGG Protocols, Interagency Workflow. She sent a note to O’Brien with three sentences that felt insufficient and therefore correct: We did it. Your insistence mattered. Thank you.

On her way out that night she drove—without siren, without ceremony—past a stretch of county road near where Bramwell meets County Line 4. The light was winter’s end kind: slant and silver. The shoulder grass, short. These drives are not pilgrimage. They’re acknowledgments. The map that betrayed a girl’s routine is also the map of a state that refused to let the betrayal be the last entry.

XI. The Community That Stayed — How Towns Remember Without Becoming Museums

Millbrook will always have two timelines: before and after September 12, 1968; before and after March 2024. The town has chosen to honor both without letting either define it entirely.

– The school board dedicated a small corner of the library to a “Rural Justice” exhibit—primary sources from the case, anonymized where they should be; a timeline of forensic science advances rendered in terms anyone can understand; a QR code linking to resources for families with missing loved ones.

– The firehouse—once the FBI command post—hosts an annual volunteer day: evidence-organization drives to help the county archive box and catalog items at risk of neglect. High schoolers earn service hours; retirees bring coffee; the day is more cheerful than the impetus and that is okay.

– The Lutheran church set up a fund named for Margaret and Robert, whose way of loving each other was to break differently and stay. It pays for counseling for families navigating fresh losses—not because tragedies map one-to-one, but because standing next to someone who understands how grief colonizes a house is a public service.

Communities can turn pain into performance. Millbrook didn’t. It turned it into policy and neighborliness and the modest plaque that tells the truth with a minimum of scripting.

XII. The Takeaways That Travel — For Departments, For Families, For Anyone Who Keeps a Box

Here’s the part that should move beyond Millbrook:

– Build boring excellence. Invest in evidence storage, chain-of-custody training, and cross-county case software. You cannot schedule miracles. You can budget for refrigerators.

– Use genetic genealogy ethically and loudly. Seek court oversight. Pre-register policies. Publish usage reports annually. The legitimacy you earn will keep this tool available.

– Treat families as partners. Give them a contact, not a switchboard. Share what you can. Correct gently. Accept their persistence as an asset, even when it challenges your cadence.

– Resist narrative inflation. “We don’t know” is sometimes the most professional sentence in the room until the day you can say “Now we do.”

– Remember that closure is not an end state. It’s a shift—from asking “whether” to telling “how.” The telling matters.

If you want to turn this case into a checklist, you can. Just remember the checklist’s point is not to streamline emotion but to sustain rigor.

Epilogue: The Box Replaced, the Record Made, the Light Kept

In the Springfield headquarters database, Sarah’s entry now carries a different status code. The screen looks the same to anyone who didn’t sit with it for years, but Rodriguez knows how letters can make a hallway seem wider. In the county archive, the space where the misfiled box once lived was filled by another older case moving into evidence stabilization. No shelf sits empty for long.

The ceramic horse will not go back to a windowsill. It will live in a climate-controlled drawer, occasionally brought into a room where families sit to see the artifacts that survived what their loved ones didn’t. Objects do that: they take on missions their makers never imagined. The rest of Sarah’s belongings—the sweater, the fragments—remain sealed, logged, available for any future technique that might speak more softly and more fully than the ones we have now. Science doesn’t stop; it revises.

Michael drives the farm roads sometimes, not to reconstruct a route—he’s done that in his head ten-thousand times—but to remind himself that landscapes can hold both harm and goodness without contradiction. He visits the cemetery on clear mornings and gray afternoons, because weather is not a moral. He runs the foundation with a board that includes an archivist, a rural sheriff, a lab tech, and a grief counselor, because success needs to be engineered.

And if you asked him what changed in March 2024, he’d likely say: everything that needed to and nothing that shouldn’t have. His sister is still gone. His parents are still buried. But a state told the truth in a way that can be footnoted. That matters.

The last line of the official closing memo is unadorned—just as it should be: Case status: cleared by exception. Offender: identified (deceased). Disposition: homicide. Supporting evidence: DNA profile match; genealogical convergence; recovered property; cross-jurisdictional corroboration. Prepared by: Det. A. Rodriguez.

To outsiders, it reads like a form filled. To those who waited 56 years, it reads like the gentle click of a latch at last catching—a door not slammed in anger, but closed in care, so that the people inside can rest and the people outside can go on to the next house in need of such work.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load