April 12, 1945. President Franklin D. Roosevelt died.

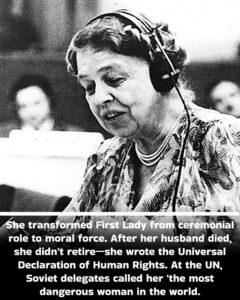

His widow, Eleanor, was 60 years old. She’d been First Lady for 12 years—longer than anyone in history. She’d redefined the role, traveling the country, championing civil rights, speaking for those without power.

Now, everyone assumed, she would retire. Fade gracefully into widowhood. Write her memoirs. Tend her garden.

Eleanor Roosevelt had other plans.

She went to the United Nations and wrote the document that would define human rights for the entire world.

And when Soviet delegates tried to stop her, calling her “the most dangerous woman in the world,” she smiled and kept working.

Because Eleanor Roosevelt didn’t retire. She escalated.

This is 1945. World War II had just ended. Fifty million people were dead. The Holocaust had revealed humanity’s capacity for systematic evil. Hiroshima and Nagasaki had demonstrated our ability to destroy entire cities in seconds.

The world needed something—some framework, some agreement that certain human dignities were universal and inviolable, regardless of nationality, race, or political system.

The newly formed United Nations took on this impossible task: get the world to agree on what “human rights” meant.

President Harry Truman appointed Eleanor Roosevelt as a U.S. delegate to the UN General Assembly in December 1945. Many thought it was a ceremonial gesture—honoring FDR’s widow with a symbolic position.

They were wrong.

Eleanor was assigned to Committee Three—the committee on humanitarian, social, and cultural affairs. Not exactly the prestigious assignment. But Committee Three had one crucial responsibility: drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Eleanor became chair of the UN Commission on Human Rights in 1947. Her mission: get representatives from completely different political systems, cultures, and ideologies to agree on a single document defining fundamental human rights.

It was impossible. The Soviet Union and the United States were already locked in Cold War hostility. Colonial powers like France and Britain resisted language that might challenge their empires. Developing nations wanted economic rights included. Religious conservatives objected to certain freedoms.

Every sentence would be a battle.

Eleanor was 63 years old, a widow, with no official government position beyond her UN appointment. She had no legal training. No diplomatic credentials. No formal authority.

What she had was something more powerful: moral clarity, relentless work ethic, and absolute refusal to give up.

The drafting process took nearly two years. Eighty-one sessions. Endless debates over every word, every phrase, every implication.

The Soviet representative, Alexei Pavlov, opposed nearly everything Eleanor proposed. He called the declaration “Western imperialism disguised as universal principles.” He argued that economic rights should supersede individual freedoms. He tried to stall, to water down, to kill the document entirely.

Eleanor debated him calmly, persistently, devastatingly. She’d arrive at sessions with detailed notes, historical precedents, philosophical arguments. She’d stay late into the night negotiating with delegates from different factions.

Her strategy was to find language universal enough to transcend political systems but specific enough to have meaning. Rights that applied to every human being simply by virtue of being human—not granted by governments, but inherent and inalienable.

Article 1 became the foundation: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

Simple. Profound. Universal.

But every article after that was a fight.

Freedom of speech, religion, assembly—the Soviets argued these were tools of bourgeois oppression.

Right to education, healthcare, social security—Western capitalists worried this endorsed socialism.

Equality regardless of race, sex, language, or religion—colonial powers objected to implications for their colonial subjects.

Eleanor negotiated, compromised where she could, held firm where she couldn’t. She worked 18-hour days. She missed family gatherings. She traveled constantly between New York and Geneva.

By December 1948, she’d built enough consensus to bring the Declaration to a vote.

On December 10, 1948, at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris, the UN General Assembly voted on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The vote: 48 in favor, 0 against, 8 abstentions (mostly Soviet bloc countries and South Africa).

Not a single country voted no.

Eleanor Roosevelt had done something almost impossible—gotten the world to agree on fundamental human dignity.

The General Assembly gave her a standing ovation. Delegates from enemy nations applauded together. For one moment, the vision she’d articulated seemed possible: that we really might be “One World,” that injury to any might be recognized as injury to all.

The Soviet delegate who’d fought her for two years grudgingly acknowledged her achievement. Alexei Pavlov reportedly told a colleague: “She is the most dangerous woman in the world.”

He meant it as an insult. Eleanor took it as a compliment.

Because she was dangerous—to tyranny, to oppression, to any system that denied human dignity.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights didn’t end injustice. It didn’t prevent future wars or genocides. It didn’t force immediate compliance from any nation.

But it created a standard. A measuring stick against which every government could be judged. A document that activists from Mandela to Martin Luther King Jr. would cite when demanding justice.

It’s been translated into over 500 languages—more than any other document except religious texts. It’s influenced constitutions in dozens of countries. It’s the foundation for international human rights law.

And it exists because a 63-year-old widow decided retirement wasn’t an option.

But here’s what makes Eleanor’s story even more remarkable: the Declaration was just one part of her post-White House life.

She continued serving at the UN until 1952. She wrote a daily newspaper column, “My Day,” read by millions. She lectured around the world. She championed civil rights in America, confronting segregationists and supporting the early Civil Rights Movement.

She pushed President Truman to desegregate the military. She resigned from the Daughters of the American Revolution when they refused to let Marian Anderson perform at Constitution Hall because she was Black. She supported integration, voting rights, anti-lynching legislation—positions that made her controversial and cost her friendships.

President Kennedy reappointed her to the UN in 1961. She was 76 years old and still working.

She finally slowed down in 1962 when illness—aplastic anemia—forced her to step back. She died on November 7, 1962, at age 78.

At her funeral, President Kennedy, President Truman, President Eisenhower, and Vice President Johnson all attended. Adlai Stevenson gave the eulogy: “She would rather light a candle than curse the darkness.”

But perhaps the truest measure of her impact came from ordinary people. Thousands lined the streets. Letters poured in from around the world—from civil rights activists she’d supported, from refugees she’d helped, from people who’d never met her but felt she’d been their advocate.

Because that’s what Eleanor Roosevelt understood: that privilege came with responsibility. That power—even the informal power of being a former First Lady—should be used for those without it.

She’d grown up wealthy, part of New York’s elite. Her uncle was President Theodore Roosevelt. She married her distant cousin Franklin and became part of one of America’s most powerful political families.

She could have lived comfortably, doing charity work, hosting parties, enjoying the privileges of her class.

Instead, she spent her life fighting for people who had none of those privileges.

During her White House years, she’d held press conferences—something no First Lady had done before—but only for female reporters, forcing newspapers to hire women. She’d traveled to coal mines and migrant camps, investigating conditions firsthand. She’d championed anti-lynching legislation and challenged FDR’s administration to do more for Black Americans and the poor.

After Franklin died, she could have stopped. She was 60. She’d already done more than most people accomplish in a lifetime.

But she saw the UN work as the culmination of everything she believed: that humans shared fundamental dignity, that national boundaries couldn’t justify cruelty, that “we are One World.”

The Universal Declaration opens with those words she fought for: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

Not “all Americans.” Not “all white people.” Not “all Christians” or “all men.”

All human beings.

That was Eleanor’s vision—radically inclusive for 1948, still aspirational today.

She didn’t write every word of the Declaration—the drafting committee included representatives from many nations. But she chaired the commission, drove the process, built the coalitions, and refused to let it fail.

And when it passed, she understood it was just a beginning.

“Where, after all, do universal human rights begin?” she asked in 1958. “In small places, close to home—so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world… Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere.”

She was right. The Declaration didn’t automatically change anything. But it gave people a language to demand justice, a standard to point to, a vision of what was possible.

Eleanor Roosevelt: October 11, 1884 – November 7, 1962.

First Lady. UN delegate. Human rights champion.

The woman who lost her husband and gained a global mission.

Who was called “the most dangerous woman in the world”—and earned it.

Who wrote in her own words what she believed: “In the end, we are One World, and that which injures any one of us, injures all of us.”

And then spent the rest of her life trying to make that true.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load