Old Blood and Guts: The Secret That Burned in Luxembourg

Chapter 1: A Frozen Morning

January 4th, 1945. Luxembourg.

The winter of 1945 was the coldest in Europe in three decades. Snow blanketed the Ardennes, turning the forests and fields into a frozen wasteland where frostbite claimed as many victims as enemy fire. Inside a converted chateau, headquarters for the United States Third Army, General George S. Patton stood with his back to the room, warming his hands by a crackling fire. The radiators were cold. The only comfort came from the flames and the knowledge that his army had just performed the impossible—relieving Bastogne and turning the tide of the Battle of the Bulge.

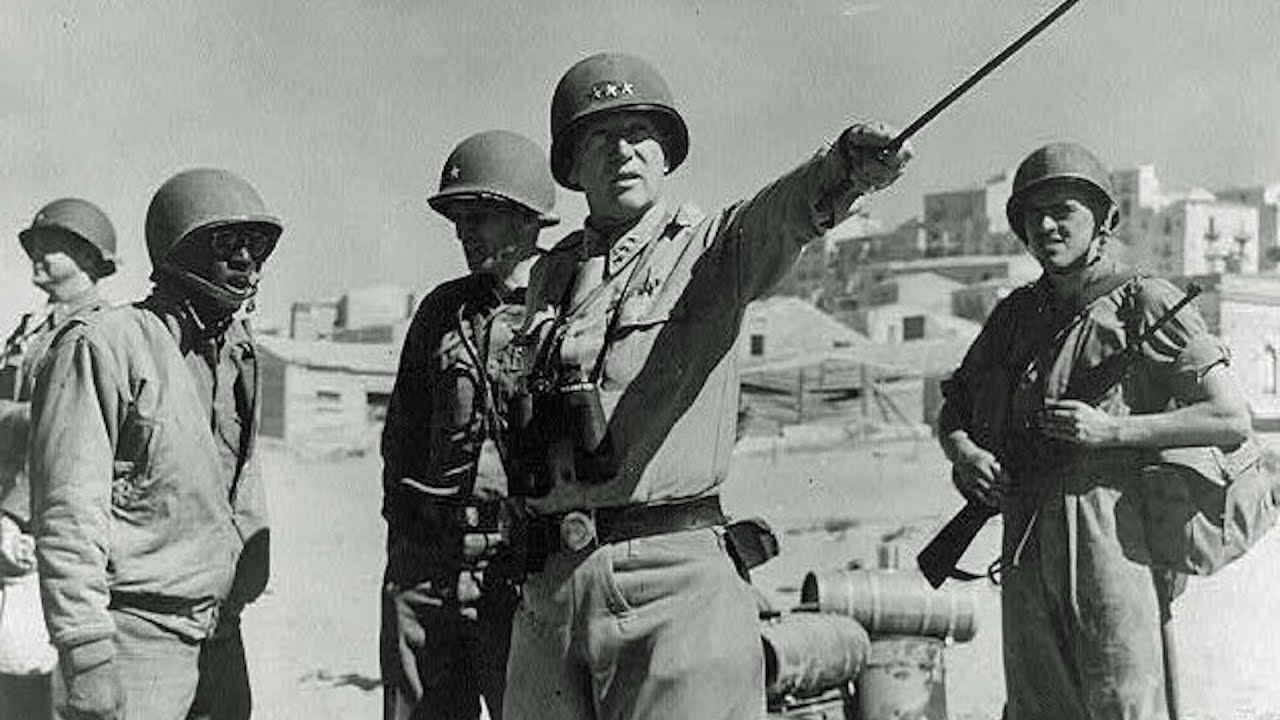

Patton was a legend. “Old Blood and Guts,” they called him—a moniker earned through years of leading from the front, charging into battle with pearl-handled pistols while other generals commanded from safe distances. He was a warrior poet, convinced that war was humanity’s highest calling, and by January 1945, he was the most aggressive and successful field commander in the European theater.

But on this morning, a single decision would test not only Patton’s reputation but the moral foundation of the United States Army itself.

A major from the Inspector General’s office stepped into the room, clutching a thick manila folder stamped “Top Secret.” Inside were sworn statements, ballistic reports, photographs of bodies in the snow, and a list of names. The file documented a massacre—one not committed by the Nazis, but by American soldiers.

Patton turned, his steel blue eyes lingering on the folder, then on the fire, and finally on the major’s face. He did not open the file. He did not ask for the names. He did not demand an explanation. Instead, he reached out, grabbed the evidence, and walked toward the flames.

The major watched in stunned silence. Patton wasn’t going to punish the men responsible. He was going to make the crime disappear.

Chapter 2: The Trigger

To understand why Patton would make such a choice, it’s necessary to revisit the forests of Belgium in the winter of 1944.

December 17th, 1944. Near Malmedy, Belgium.

The temperature had dropped below freezing. The Battle of the Bulge was more than a military offensive—it was chaos incarnate. The rules of civilized warfare dissolved into snow and blood.

At noon, a convoy of the United States 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion ran into the lead elements of Kampfgruppe Peiper, a ruthless Waffen-SS Panzer unit. Surrounded and outgunned, the Americans surrendered. The SS troopers disarmed them, herded 120 men into a snow-covered field, and then, without warning, opened fire.

For ten horrific minutes, the snow turned crimson. Eighty-four American prisoners of war fell dead. Some were killed instantly; others were wounded, then shot at point blank range. A handful survived by playing dead, letting the blood of their friends freeze onto their uniforms until darkness allowed them to escape.

Their testimony spread through Patton’s Third Army like wildfire. “Malmedy” became a curse, a rallying cry, a permission slip written in blood. The unspoken order went down through every division: The SS are not soldiers. They are animals. And animals do not deserve the protection of the Geneva Convention.

Patton himself addressed his officers. “We’re not just fighting Germans,” he said. “We’re fighting SS fanatics who murder prisoners. From now on, we fight fire with fire.”

His words were clear. But none of his men realized how literally they would be interpreted.

Chapter 3: The Cycle of Vengeance

January 1st, 1945. The village of Chenogne, Belgium.

The fighting was brutal and intimate—house to house, room to room. By mid-afternoon, elements of the United States 11th Armored Division had secured the village and captured a group of German soldiers—approximately sixty men of the Waffen-SS. They were disarmed, hands raised, standing in a snowy field.

This was not a chaotic firefight. It was not combat. An American machine gunner set up his tripod, loaded the ammunition belt, and waited. Officers stood by. The order was given. The machine gun roared.

Sixty German prisoners were cut down in waves. Those who survived the initial burst were finished off with rifles. Some tried to run and were shot in the back. The snow turned red.

The killing took less than five minutes. It was a mass execution—carried out by young Americans who had come to Europe to be liberators, to fight for freedom, to uphold the values of their country.

The Chenogne massacre was complete. The cycle of vengeance had come full circle. Malmedy had been answered.

But the question remained: What would happen when the truth reached the highest levels of command?

Chapter 4: The Investigation

You cannot hide sixty bodies forever. Rumors reached the rear echelon within hours. Belgian civilians watched from their windows. Other American officers saw the aftermath.

By January 2nd, the Inspector General’s office launched a formal inquiry. Investigators collected sworn statements, testimony from Belgian villagers, ballistic reports, and photographs. The evidence was overwhelming.

The file named the unit: the 11th Armored Division. It named specific officers and sergeants. It outlined charges that, under the Articles of War, carried mandatory penalties—including death by hanging for the murder of prisoners of war.

This was not a case of a few rogue privates losing control. The implications went straight up the chain of command. If this went to trial, it would not just be a legal proceeding—it would be a propaganda catastrophe for the United States.

The file moved up the ladder, stamp by stamp, signature by signature, until it reached the highest authority in the sector.

Chapter 5: The Decision

January 4th, 1945. Luxembourg.

The stone room was silent except for the crackling fire. The Inspector General’s major stood at attention, watching Patton’s face, waiting for the explosion.

Patton picked up the file, feeling its weight. He looked at the major with legendary steel blue eyes.

“What is the nature of these allegations?” Patton’s voice was dangerously calm.

“The killing of prisoners, General. Approximately sixty German soldiers of the Waffen-SS executed after surrender by elements of the 11th Armored Division near Chenogne.”

Patton nodded slowly, jaw tight. For a moment, the major thought he saw rage—but it was not directed at the soldiers who committed the massacre. It was directed at something else.

“When did this supposedly occur?” Patton asked.

“January 1st, General. New Year’s Day.”

“Four days after we relieved Bastogne,” Patton said quietly. “Four days after my men fought through a blizzard to save ten thousand surrounded troops. Four days after the 11th Armored helped break the German offensive.”

Patton walked slowly toward the fireplace. The orange glow illuminated the deep lines in his face—a man who had sent thousands to their deaths, made impossible decisions, and never apologized for being a warrior in a world that increasingly didn’t understand warriors.

He looked at the top secret stamp one last time. Then he turned to the major and delivered a verdict that would never be written in any official record.

“There are no murderers in this army, Major,” Patton said. “And I will not have my men prosecuted for killing the sons of bitches who massacred our boys at Malmedy.”

With a flick of his wrist, Patton tossed the file into the roaring fire. The paper curled, caught flame, and turned black. The typed words blurred and disappeared. The photographs crackled and shriveled. The names vanished. The testimony of Belgian witnesses became ash. The ballistic reports dissolved into smoke.

Justice for sixty dead German soldiers went up the chimney in a wisp of gray smoke.

Patton stood there, hands clasped behind his back, watching it burn.

Chapter 6: The Silence That Followed

Outside the chateau, snow continued to fall on Luxembourg, muffling the world in a hush that felt almost sacred. Inside, the silence after Patton’s decision was heavier than the cold. The Inspector General’s major stood rigid, his sense of duty colliding with the reality he had just witnessed.

He knew what had happened. The highest-ranking officer in the European theater had made a choice—not just to destroy a file, but to rewrite the fate of men, the memory of a massacre, and perhaps the moral compass of the Army itself.

The major saluted. Patton’s response was slow, almost dismissive. The major left the room, closing the heavy oak door behind him. His hands shook. He leaned against the stone wall in the hallway, wrestling with the knowledge that outside these walls, the United States was fighting for democracy, freedom, and the rule of law. But inside that room, the law had just died in flames.

Back in the office, Patton’s aide—a young captain—poured a drink, his hand trembling. “Sir, the implications—” he began.

But Patton cut him off, voice flat. “That’s none of your goddamn business, Captain.”

Patton stared out the window at the falling snow. Somewhere out there, his Third Army was preparing for the next push into Germany. The 11th Armored Division was checking tanks, loading ammunition, getting ready to roll. They would never know how close they had come to being destroyed, not by enemy fire, but by American justice.

Patton had saved them. He had chosen his men over the law. But at what cost?

Chapter 7: The Ripple Effect

The consequences of Patton’s decision rippled through the Third Army immediately. The officers and men of the 11th Armored Division were not arrested. No military police appeared. The investigation simply vanished as if it had never existed.

But the message was clear: The old man has our backs. Kill the SS. Don’t take prisoners. We’ll never be punished.

For the rest of the campaign into Germany, fighting in Third Army sectors became particularly savage. Prisoners were rarely taken in combat with SS units. When Waffen-SS soldiers tried to surrender, they were often told to keep running—and were shot. The brutal efficiency of Patton’s divisions increased. They fought with a reckless, desperate edge, knowing they were untouchable.

But the moral cost was corrosive. Young men who had come to Europe to be liberators had been given a pass to be executioners. The stain of Chenogne did not wash off. It settled deep into the psyche of the soldiers who were there, who knew what happened, who understood that justice had been burned in a Luxembourg fireplace.

Chapter 8: The Calculus of Command

Why did Patton do it? Why did a general known for discipline, who once court-martialed officers for minor infractions, protect soldiers who committed murder?

Patton was not a policeman in uniform, nor a lawyer in olive drab. He was a warrior prophet who believed war was not a legal exercise, but a primal struggle for survival. To Patton, the battlefield was not a courtroom—it was an arena where the strong destroyed the weak, where hesitation meant death, where the only unforgivable sin was cowardice.

He knew the 11th Armored Division was about to be thrown back into combat, attacking fortified German positions, fighting SS fanatics who would give no quarter. He needed them aggressive, lethal, and convinced their commander stood behind them.

If he court-martialed those responsible for Chenogne, Patton believed it would break the spirit of the entire division. It would send a message: Your general cares more about dead Germans than living Americans. Fight aggressively at your own legal risk.

Patton could not accept that. He had studied ancient battles, medieval knights, Napoleon’s campaigns. He believed modern warfare had been infected with humanitarian ideals that got soldiers killed. After Malmedy, Patton had dehumanized the SS. In his mind, they were not soldiers entitled to Geneva Convention protection—they were rabid dogs that needed to be put down.

Erasing the Chenogne massacre was, to Patton, not a crime but a necessary act of command—a tactical decision to preserve the fighting spirit of his army.

Chapter 9: The Weight of Memory

The consequences of Patton’s choice extended beyond the battlefield. General Omar Bradley, Patton’s superior, later wrote in his memoirs that he heard rumors about prisoner killings in Third Army sectors, but never pursued them. He knew Patton’s methods. He knew “Old Blood and Guts” believed in total war. Bradley made his own calculation: Patton’s aggressive tactics were winning battles and saving American lives. If some German prisoners died, that was the cost of victory.

Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, the British commander, was more critical. Years later, he said, “Patton was a brilliant tank commander, but a barbarian. He won battles, but he lost his soul.”

German commanders, after the war, admitted they feared Patton more than any other Allied leader. “We always knew where Patton was,” one general said, “because that’s where the fighting was most ferocious. His soldiers fought like demons. They took no prisoners. They showed no mercy.”

Even Joachim Peiper, the SS officer responsible for the Malmedy massacre, said during his war crimes trial, “Your General Patton understood total war. He was more like us than you want to admit.”

Chapter 10: The Aftermath

The Third Army rolled onward, deeper into Germany. The men of the 11th Armored Division returned to their tanks and halftracks, loaded shells, and advanced. The investigation was gone, erased by command. But the memory of Chenogne lingered—a secret shared by those who had been there, a weight carried in silence.

For some, Patton’s decision was a shield. They fought with new ferocity, certain their general would protect them, whatever they did. But for others, the events of that frozen day in Belgium became a shadow. Some would speak of it only in whispers at reunions, others never at all. A few, in their final years, confessed to chaplains and historians what they had seen and done.

The stain of Chenogne was not visible in medals or parades. It lived in nightmares, in the quiet moments after the war, in the knowledge that justice had been burned away with a handful of papers in a Luxembourg fireplace.

Chapter 11: The Legend and the Secret

History, as always, was written by the victors. The Malmedy massacre became one of the most infamous atrocities of World War II, prosecuted at the Dachau war crimes trials. The world knew about Malmedy. It became a symbol of Nazi brutality.

But Chenogne disappeared. There were no trials, no hangings. The 11th Armored Division went down in history as heroes of the Battle of the Bulge. Their secret was protected by the legend of “Old Blood and Guts.”

General Patton never spoke publicly of Chenogne. His diaries from that period are carefully edited, omitting any mention of the investigation. After the war, before his untimely death in December 1945, he gave interviews about strategy, tank warfare, and his rivalry with Montgomery—but never about the fire in Luxembourg.

Did Patton regret his decision? We’ll never know. He was not a man given to public self-doubt. He believed, until his dying day, that he had fought the war the only way it could be fought: with absolute aggression, total commitment, and unwavering support for his soldiers.

Chapter 12: The Truth Surfaces

For seventy years, the story of Chenogne remained hidden—only whispered among veterans, never taught in classrooms. It wasn’t until the 1990s, when classified archives were opened and old soldiers began to speak, that historians started to piece together what really happened.

Belgian witnesses gave interviews. American veterans admitted what they had seen. The physical evidence was gone, destroyed by Patton, but the memory could not be erased.

Today, the United States Army War College teaches Chenogne as a case study in the ethics of command. Officers study it, asking: What would you have done in General Patton’s position? There is no easy answer.

Chapter 13: The Ethics of Command

Patton’s choice forces us to confront uncomfortable truths. Is the law absolute, even in war? Does survival justify the suspension of justice? Should a general’s first duty be to the abstract concept of justice, or to the concrete reality of his soldiers’ lives?

Patton answered that question on January 4th, 1945. He chose his men. He chose victory. He chose to be remembered as “Old Blood and Guts”—the warrior who never apologized, never retreated, never let legal niceties interfere with winning battles.

The soldiers of the 11th Armored Division went on to liberate Nazi concentration camps. They saw the gas chambers and mass graves. Some, in their final years, said that Chenogne made more sense after they saw what the SS had been fighting for. Others carried the guilt to their graves, knowing that becoming like the enemy, even for a moment, meant losing something essential.

Epilogue: The Fire and the Truth

The fire in that Luxembourg chateau destroyed the official record. But it couldn’t destroy the truth.

Victory in war—even a just war—comes at a cost we rarely acknowledge. Sometimes that cost is measured in the bodies of enemy prisoners lying in the snow. Sometimes it’s measured in the corruption of justice. And sometimes it’s measured in the knowledge that the heroes we worship are also the men who hold the match.

We like to remember General George S. Patton as the pearl-pistol-wearing warrior poet who raced across France and saved Bastogne. We want him to be the uncomplicated hero, the embodiment of American fighting spirit. The legend is too valuable to complicate with moral ambiguity.

But the truth is always more complicated than the legend. Patton was brilliant, brave, and the greatest tank commander in military history. He understood mobile warfare better than any American general before or since. His aggressive tactics saved countless lives by ending the war faster. He was also willing to burn evidence of a war crime to protect his soldiers and preserve their edge.

He chose military effectiveness over justice. He chose victory over morality. And in making that choice, he forced us to ask: Was he right?

That question has no easy answer. It depends on whether you believe the law should apply equally in wartime, or whether war creates conditions where survival trumps justice. It depends on whether you believe a general’s first duty is to his men, or to the ideals he fights for.

On that frozen morning in Luxembourg, Patton made a choice that defined his legacy. He burned the evidence. He protected the killers. He chose war over law. And in doing so, he proved that even the greatest heroes are capable of the darkest compromises.

This is the story they don’t teach in school. This is the legend behind the legend. This is what General George S. Patton did when he found out his soldiers executed fifty SS guards. He made sure no one would ever know—until now.

News

Why US Pilots Called the Australian SAS The Saviors from Nowhere?

Phantoms in the Green Hell Prologue: The Fall The Vietnam War was a collision of worlds—high technology, roaring jets, and…

When the NVA Had Navy SEALs Cornered — But the Australia SAS Came from the Trees

Ghosts of Phuoc Tuy Prologue: The Jungle’s Silence Phuoc Tuy Province, 1968. The jungle didn’t echo—it swallowed every sound, turning…

What Happened When the Aussie SAS Sawed Their Rifles in Half — And Sh0cked the Navy SEALs

Sawed-Off: Lessons from the Jungle Prologue: The Hacksaw Moment I’d been in country for five months when I saw it…

When Green Berets Tried to Fight Like Australia SAS — And Got Left Behind

Ghost Lessons Prologue: Admiration It started with admiration. After several joint missions in the central Highlands of Vietnam, a team…

What Happens When A Seasoned US Colonel Witnesses Australian SAS Forces Operating In Vietnam?

The Equation of Shadows Prologue: Doctrine and Dust Colonel Howard Lancaster arrived in Vietnam with a clipboard, a chest full…

When MACV-SOG Borrowed An Australian SAS Scout In Vietnam – And Never Wanted To Return Him

Shadow in the Rain: The Legend of Corporal Briggs Prologue: A Disturbance in the Symphony The arrival of Corporal Calum…

End of content

No more pages to load