Prologue: Charleston, August 12th, 1849

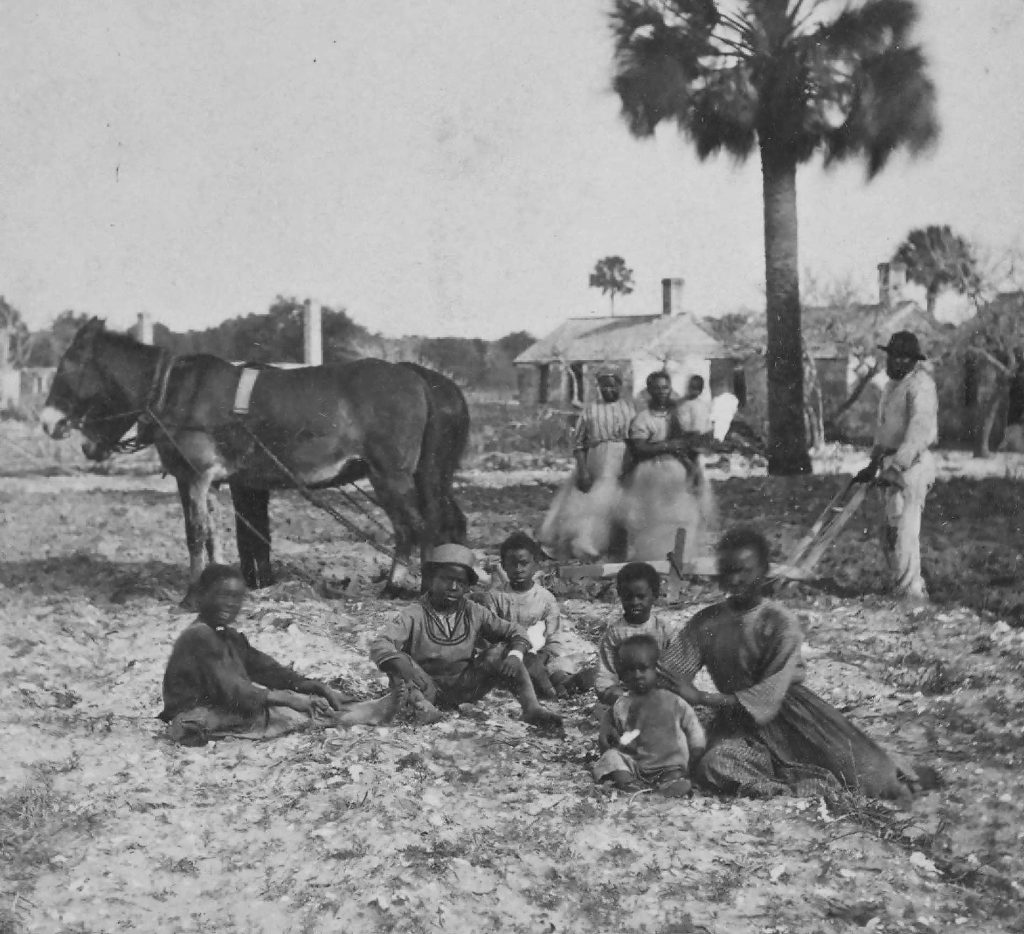

The morning sun pressed down on Charleston, South Carolina, like a heavy hand. The city’s harbor bustled with merchant ships, their sails bright against the humid sky. Grand mansions lined the battery, their piazzas catching the sea breeze, while just blocks away, the slave markets operated with grim efficiency. In the auction house on Chararma Street—a plain, two-story brick building with barred windows—twelve souls stood waiting to be sold. Among them, a small child no older than seven, silent, terrified, clutching a battered leather journal to his chest.

The auctioneer, Samuel Rutled, prided himself on detailed records. He noted names, prices, skills, and features in his ledgers, each entry written in his careful hand. But this child was different. He had arrived separately, brought in by Harrison Vance, a trader known for unusual cases. Vance explained, sweating in the oppressive heat, that the boy had come from a Portuguese ship. His mother had died of fever at sea. Someone paid the captain to bring the boy to shore, but Vance didn’t care who. “Just want him sold and gone,” he muttered.

The boy’s skin was darker than most enslaved people passing through Charleston, suggesting origins far from the American South. He wore clothes too large for his small frame, and he clung to the journal as if it were the only thing tethering him to earth. Vance had tried to decipher the writing inside—perhaps Arabic, a merchant guessed—but the boy refused to speak or let go of the book.

Rutled entered the child into his ledger with minimal detail: “Male child, approx. 7 years, origin unknown. Mute. Arrived with personal effects including one journal.” The auction began at ten. By noon, eleven people had been sold. The child was last. Rutled expected little interest—a boy too young for labor, too silent, too foreign. But when the child was brought forward, something unexpected happened.

A man stepped from the back of the crowd—tall, dressed in dark clothes despite the heat, his face carved from stone. His accent was northern, rare and often suspect in Charleston. “I’ll give you $3 for the child,” he said, his voice clear and unwavering. Rutled bristled at the insultingly low offer, but the stranger added, “And I’ll take the journal with him.” The intensity in his eyes unsettled Rutled. Something told him to close the deal quickly.

The transaction was recorded. The stranger paid in silver coins, took the child’s hand, and vanished into the crowded streets. Rutled watched them disappear, a cold sensation creeping down his spine. He’d conducted thousands of sales, but this one felt different. That night, he poured himself a generous whiskey, trying to forget the child’s watchful eyes. He didn’t record the buyer’s name—a lapse he’d later claim was forgetfulness, though the truth was more mysterious. Even hours after the sale, Rutled couldn’t recall the stranger’s face, as if it refused to fix itself in memory.

The child and the stranger left Charleston that afternoon on a coastal steamer heading north. No passenger manifest survives, but the ship’s log confirms its departure. Somewhere along the route, the child and the stranger disembarked. What transpired during that journey would remain unknown for years.

I. The Silent Years: Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 1849–1853

In September 1849, a child matching the boy’s description appeared at a Quaker school in rural Pennsylvania, near Lancaster. The school, run by Patient Hadley, provided education to free Black children and, secretly, to escapees moving through the Underground Railroad. Patient kept no official records, but her diaries survived.

On September 18th, she wrote: “A child has come to us, brought by a man who would not give his name. The boy does not speak, but his eyes show intelligence and deep sorrow. He carries a book written in strange letters that none of us can decipher. The man said only that the child must be taught to read and write English, and that under no circumstances should the book be taken from him.” He left $50 in gold for the child’s care—far more than necessary—and departed before Patient could ask questions. “We’ve become guardians of something far more significant than an orphan child,” she wrote.

The child stayed at the school for four years. He learned English with remarkable speed, though he never revealed his name or origin. The other students called him “Book,” for the journal he refused to let anyone read. Patient noted his progress—his aptitude for mathematics, his ability to memorize long passages, his habit of waking before dawn to practice writing by candlelight. But she also noticed something troubling: every few months, strangers appeared, asking about new students and unusual possessions. Someone was searching for the child. Multiple someones, working independently.

In May 1853, Patient made a decision that would alter the child’s life. A traveling scholar, Dr. Edwin Hartwell, visited Lancaster, specializing in ancient languages. Patient showed him the journal, hoping for identification. Hartwell examined it for hours, then looked up, pale. “Where did you get this?” he whispered. He could read portions—Arabic, but archaic, mixed with North African symbols. “This journal contains information many would consider dangerous. Historical records of events certain powerful families would prefer forgotten. The child is in danger. If the wrong people discover what’s written here, they’ll do anything to obtain it. They’ll kill for it.”

Patient asked what she should do. “Teach him to be invisible,” Hartwell said. “And for God’s sake, teach him never to show that journal to anyone.” Hartwell left that day. Two weeks later, three men broke into the school, searching every room, questioning the children about a boy with a foreign book. Patient and her older students drove them off, but the message was clear: the child was no longer safe.

Using Underground Railroad contacts, Patient arranged for the boy to travel north to Albany, New York, to a family named Thatcher. The night before he left, Patient dared to ask: “Child, do you know what’s written in that journal?” The boy, no longer quite a child, looked at her with eyes far older than his years. “My mother told me,” he said quietly. It was the first time he mentioned her directly. “She said it’s the truth about where we came from and where we were going. Powerful men stole our history and wrote lies to replace it. This journal proves their lies, and that’s why they want it destroyed.”

“What history?” Patient asked.

“Our history,” the boy said. “African history. The history they don’t want anyone to know because it shows that what they do to us, what they did to my mother, is built on theft and murder going back hundreds of years. The journal has names, places, transactions, proof.”

Patient felt the weight of that knowledge settle onto her shoulders. “And you’ve kept me safe all these years,” the boy added. “It’s all I have of her. And it’s the truth that matters.”

He left the next morning. Patient never saw him again, but his words haunted her for the rest of her life.

II. Albany and the Underground: 1853–1861

The boy arrived in Albany in June 1853, taken in by Marcus and Judith Thatcher, who ran a cooperage producing barrels for merchant trade. Marcus, a free Black man, had purchased his own freedom twenty years earlier. Judith was born free in New York. They had no children, welcoming the boy without questions about his past.

The boy finally chose a name: Thomas Freeman—symbolizing freedom and a new beginning. He proved valuable to the business, clever with his hands and gifted in mathematics. The cooperage prospered, but Thomas never forgot Dr. Hartwell’s warning or the men who’d ransacked Patient’s school. He kept the journal hidden in a waterproof pouch beneath the floor, telling no one, not even the Thatchers.

Albany in the 1850s was a city of intense political activity. Slavery debates consumed the nation, and New York was divided between abolitionists and those with southern ties. The Underground Railroad ran through the city, both sides watching for advantage. Thomas listened to debates, read newspapers, and understood the country was moving toward catastrophe. The system that killed his mother was unsustainable—it would either be dismantled or tear the nation apart.

In 1857, the Supreme Court issued its Dred Scott decision, declaring Black people could never be citizens. Thomas was fourteen. That night, for the first time in years, he read his mother’s journal by candlelight. The earliest entries dated to the 1700s, documenting transactions between European traders and African merchants—transactions misrepresented in official records to justify the slave trade. His mother had accessed ledgers, letters, and bills of sale, documenting the deliberate manipulation that transformed prisoners of war and criminals into supposedly permanent chattel.

But there was more. The later pages listed American names—families in Charleston, Richmond, Savannah, New Orleans—who’d built fortunes on the slave trade and gone to extraordinary lengths to hide their involvement. Dates of crimes, murders disguised as accidents, forged documents claiming ownership of free people, conspiracies to capture and sell free Black children. Thomas realized his mother must have worked in a household with access to private papers, perhaps as a domestic servant. She’d copied these records secretly over years, documenting evidence that could destroy powerful families if ever made public.

No wonder people were hunting for the journal. It wasn’t just a historical record—it was a weapon.

Thomas decided to wait. He’d keep the journal safe until the country was ready to hear its contents. He was young, but patient.

III. A Nation at War: 1861–1864

Years passed. Thomas grew into a young man, the Thatcher’s cooperage prospered, and Thomas became Marcus’s full partner. He saved money, invested wisely, and by seventeen, owned his own house. He taught himself advanced mathematics and became a successful craftsman and businessman. But beneath the surface, Thomas was preparing. He corresponded with former students from Patient’s school, made contacts with abolitionists and journalists, and carefully researched the families named in his mother’s journal.

Then, in April 1861, Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter. The nation erupted into war. Albany’s young men enlisted in Union regiments; the cooperage shifted to producing military supplies—gunpowder kegs, food barrels, water casks. Thomas was exempt from service, but watched friends and neighbors march south, many never to return.

In the chaos of war, information became currency. Both sides needed intelligence about enemy resources and leadership. The Union government established networks of spies and informers throughout the South; Confederate agents worked in northern cities, gathering information and sabotaging Union efforts.

In November 1862, a man appeared at Thomas’s door—Colonel Isaac Brennan, of the War Department in Washington. Brennan sought information about southern families, their finances, business dealings, anything that might reveal Confederate supply networks or hidden assets. “I’ve heard you might have access to historical records about certain Charleston families,” Brennan said, watching Thomas’s face. “Records that could prove useful to the Union cause.”

Thomas’s blood ran cold. How had this man learned about the journal? Had someone from his past talked, or was this simply luck or tragedy that his secret had been discovered at the worst possible moment?

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Thomas said.

Brennan smiled, but there was no warmth. “Mr. Freeman, I don’t think you understand. We’re at war. The president has suspended habeas corpus. I could have you arrested and search your property without a warrant. But I’d rather we work together. The information you have could help us end this war faster. It could save thousands of lives.”

Thomas felt trapped. His mother had wanted the journal revealed, but timing mattered. If revealed too soon or in the wrong way, it might cause more harm than good. The families named in it were powerful, with connections in government, banking, and the military. Expose them recklessly, and they’d bury the evidence and destroy anyone associated.

“I need time to think,” Thomas said.

“You don’t have time,” Brennan replied. “But I’ll give you three days. After that, I’ll return with a warrant and soldiers.”

Brennan left. Thomas stood in his empty house, feeling the weight of fifteen years of secrecy pressing down. That night, he retrieved the journal and read by lamplight until dawn. His mother’s handwriting filled the pages—small and careful, each entry a testament to her courage. One passage struck him: “They believe we are nothing. They believe we have no history worth remembering, no records worth preserving. They believe they can erase us from human memory. This journal is proof they’re wrong. Whoever reads this, my son, if you survive, or anyone else who finds it, use this knowledge wisely. Truth is a weapon, but weapons can wound the wielder. Choose your moment carefully.”

His mother had known the journal’s power and danger. Thomas made his decision. He would give Brennan the journal—but not the original. Over the next two days, Thomas created a careful copy, transcribing every entry into a new ledger in his own handwriting. He translated the Arabic sections into English, verified names and dates against newspapers and public records, and added footnotes with supporting evidence. The result was a document that could be verified, challenged, and debated—a historical record supported by contemporary sources.

When Brennan returned, Thomas gave him the transcript and supporting documents. “Where’s the original?” Brennan demanded.

“Safe,” Thomas said. “If you want the information, that transcript contains everything you need. Names, dates, transactions, all documented, all verifiable. Use it however you think best for the Union cause.”

Brennan examined the transcript. “This could embarrass important people. Some of these families still have influence in Washington.”

“Then perhaps that influence needs to be challenged,” Thomas said quietly.

Brennan nodded slowly. “Perhaps it does. Thank you, Mr. Freeman. You’ve done your country a service.”

He left with the transcript. Thomas watched him disappear, feeling both relief and apprehension. He’d given away his mother’s secret, but on his own terms. The original journal remained hidden, safe for future generations. The information was now in the hands of people who could use it. Whether they would use it wisely remained to be seen.

IV. The Reckoning: 1863–1864

For three months, Thomas heard nothing. The war continued its brutal course. Then, in February 1863, strange things began to happen. A fire broke out in the warehouse next to Thomas’s cooperage—suspicious in its timing and location. Thomas noticed he was being followed by different men, always keeping their distance. Letters went missing, business suffered, and longtime customers canceled orders.

Marcus Thatcher, now in his sixties, noticed the changes and confronted Thomas. “What have you gotten yourself into, son?” Thomas told him everything—the journal, the sale in Charleston, the years in hiding, the transcript given to Brennan. Marcus listened, his weathered face growing more concerned. “You poked a hornet’s nest,” Marcus said. “These families won’t let themselves be exposed without a fight. War or no war, they have resources and connections. They’re trying to frighten you.”

“What should I do?”

“Leave Albany tonight. Go somewhere they can’t find you. I have a cousin in Michigan, owns a lumber mill near Saginaw. No one would think to look for you there. You can work, stay safe, and wait for this storm to pass.”

Thomas resisted, but Marcus and Judith insisted. That evening, Thomas packed essentials—including the original journal—and left Albany on the night train to Buffalo. He never saw the Thatchers again. Three weeks later, the cooperage burned to the ground in a fire that killed Marcus and seriously injured Judith. The official report called it an accident, but Thomas knew better. They’d been targeted because of him.

The guilt was crushing. Thomas spent the spring of 1863 working in Michigan lumber camps, trying to outrun both his pursuers and his conscience. He sent money to Judith, but she died in June. Thomas felt responsible for both deaths. But in July, the tide turned. The Battle of Gettysburg ended in Union victory, and Thomas received a letter forwarded through multiple addresses from a journalist named Harriet Weston, who worked for an abolitionist newspaper in Boston.

Harriet had received portions of Thomas’s transcript and verified many claims through her own research. She was preparing a series of articles exposing the historical crimes documented in the transcript, but needed Thomas’s help to confirm details and, if possible, see the original journal. “President Lincoln has issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The question of slavery is no longer political. It’s moral. Your mother’s documentation could help ensure that when this war ends, the truth about how this system was built cannot be denied or forgotten. Please contact me. Let’s finish what she started.”

Thomas read the letter three times. Here was the opportunity he’d waited for—a way to ensure his mother’s work would be recognized, her sacrifice meaningful. But accepting meant coming out of hiding, making himself a target again. He thought about Marcus, Judith, Patient, and his mother. They’d all risked everything for truth and freedom. How could he do less?

Thomas wrote back to Harriet, agreeing to meet. But before revealing himself, he took one precaution—traveling to Detroit to place the original journal in a bank vault with instructions for its release if anything happened to him.

Only then did Thomas travel to Boston to meet Harriet and begin the work of transforming his mother’s documentation into a weapon against the system that had enslaved them both.

V. Truth in the Light: Boston, 1863–1864

Harriet Weston was 42 when she met Thomas Freeman in Boston in August 1863. She’d been writing for abolitionist newspapers since the 1840s, documenting the realities of slavery through interviews with escaped slaves and free Black communities. She’d seen her articles censored, her office ransacked, her life threatened, but never stopped writing.

When Thomas entered her office, Harriet saw immediately what the boy purchased for $3 had become—a young man of twenty, careful and watchful, carrying burdens far too heavy for his age. But she also saw determination and quiet strength.

“Tell me everything,” she said, and Thomas did. The telling took hours. Harriet listened without interruption as Thomas described the auction house, the silent years, the schools and safe houses, the journal he’d protected. When he finished, she studied him carefully. “Do you understand what you’re offering me? This isn’t just a story. This is evidence that could destroy powerful families. It could make you a target for the rest of your life.”

“I’ve been a target since I was seven,” Thomas replied quietly. “The difference now is that I’m old enough to fight back.”

Harriet nodded. “Then we’ll fight together, but we do this properly. Every claim verified, every name checked, every date confirmed. We give them no opening to dismiss this as fantasy or fabrication.”

They worked together for three months. Harriet had contacts throughout New England—archivists, historians, clerks, government offices who shared her abolitionist sympathies. She sent letters to archives in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New York, requesting copies of ship manifests, property deeds, and bills of sale from the early 1700s. Thomas translated sections of the journal, cross-referencing his mother’s entries with documents Harriet obtained.

What emerged was more detailed and damning than either had anticipated. The journal didn’t just document individual crimes—it revealed systematic patterns. The same families appeared repeatedly across decades, their business relationships intertwined, their legal manipulations coordinated. They’d created a conspiracy spanning generations, each new generation inheriting not just wealth but the methods and connections necessary to maintain the fiction that their system was legitimate.

One case consumed weeks of research. In 1731, a Charleston merchant named William Creswell purchased survivors from a slave ship wrecked in a storm. Among them was Kofi, a merchant from the Gold Coast traveling on legitimate business. Kreswell destroyed Kofi’s papers and sold him as a slave. When Kofi’s business partners in London sent inquiries, Kreswell claimed the entire ship had been lost with no survivors. Thomas’s mother documented this in detail, including transcriptions of letters discussing how to handle educated Africans with documentation of free status. The letters revealed a deliberate strategy—destroy the papers, isolate the individuals, sell quickly to inland plantations, maintain plausible deniability.

Harriet traced Creswell’s descendants. The family still existed in 1863, now prominent in South Carolina banking and politics. One of Creswell’s great-great-grandsons was a Confederate officer, his education and position financed by ancestral fraud.

“This is what we need,” Harriet said, studying the documentation. “Not just historical crimes, but direct lines connecting past fraud to present power—show people this isn’t ancient history. It’s the foundation their world is built on.”

By October, they had compiled enough material for a series of five articles. Harriet’s editor, Edmund Pierce, read the first draft and went pale. “Harriet, these are serious accusations against families with considerable influence. Some have relatives in Congress. Are you absolutely certain of your sources?”

“Every fact has been verified,” Harriet assured him. “Every name, every date, every transaction. Thomas’s mother didn’t document rumors. She documented crimes she had direct evidence of. If they sue us, we’ll produce the evidence in court. That might be the best outcome—a public forum to present everything we’ve found.”

Pierce struggled with the decision for a week before agreeing to publish. The first article appeared on October 15th, 1863, under the headline: “Foundations of Fraud: How America’s Slave System Was Built on Systematic Deception.”

The response was immediate and violent. Harriet received threatening letters promising arson, assault, and murder. Someone threw a brick through her office window with a note: “Lies have consequences.” Two men attempted to force their way into her apartment, but neighbors intervened. Thomas faced similar harassment—men followed him openly, his landlady asked him to leave, and he moved three times in two weeks.

But the articles also found defenders. Abolitionist societies reprinted them, ministers cited them in sermons, and Frederick Douglass wrote a response praising the documentation and calling for further investigation. The controversy grew so intense it reached Washington.

In November, Harriet received word that a congressional committee wanted to examine the evidence. Some members were genuinely interested in historical truth; others wanted to discredit the articles and protect the accused families. Thomas was summoned to appear before the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War in January 1864, bringing whatever documentation supported his allegations.

Thomas prepared carefully, bringing the transcript annotated with supporting documents, copies of ship manifests, property deeds, and court records. He did not bring the original journal, which remained in Detroit, protected by legal arrangements.

The journey to Washington took two days. Thomas traveled with Harriet and Pierce, who agreed to accompany them as a witness to the verification process. They arrived on January 10th, 1864, in a capital city transformed by war. Soldiers filled the streets, hospitals overflowed with wounded, and the atmosphere was tense.

The hearing took place in a committee room in the Capitol. Thirteen congressmen and senators sat in judgment, their faces ranging from sympathetic to hostile. Journalists, abolitionists, and representatives of the accused families filled the gallery.

Thomas stood before them and told his story, speaking for two hours about the auction in Charleston, the journal his mother protected, and the verification process he and Harriet conducted. He answered questions about entries, his mother’s sources, and how a domestic servant could access private papers.

“My mother worked in households that dealt in this trade,” Thomas explained. “Over many years, she copied documents when opportunities arose. She understood the risk. She did it anyway because she believed the truth mattered more than her safety.”

Representative Thaddeus Stevens pressed for details. “And you’ve kept this journal safe for fifteen years, through multiple moves, through people hunting for it?”

“Yes, sir. It was all I had of her. And it was the truth she died to preserve.”

Senator James Herov of Kentucky was less sympathetic. “Mr. Freeman, you were seven when you supposedly acquired this journal. How can we trust your memory? How do we know you didn’t fabricate this story, perhaps with Miss Weston’s assistance, to slander honorable families during wartime?”

Thomas met his gaze steadily. “Senator, I didn’t fabricate the ship manifests in Massachusetts archives. I didn’t fabricate the property deeds in Charleston. I didn’t fabricate the court records in Rhode Island. All those documents exist independently, created decades before I was born. My mother’s journal doesn’t create these records. It explains the connections between them. It reveals the pattern that individual documents don’t show.”

Harriet testified next, describing her meticulous verification process. She brought copies of every referenced document, organized chronologically and by family. She walked the committee through specific cases, showing how the journal’s claims matched historical records. “The journal told us where to look,” she explained. “It provided names and dates that allowed us to find corroborating evidence in public archives. If Mr. Freeman had fabricated this, he’d need access to archives across six states and the ability to connect documents from different repositories. That’s not plausible for a man of his age and background. The only reasonable explanation is that the journal is genuine.”

The committee debated for three days. Some wanted to dismiss the allegations immediately; others recognized the historical significance and called for further investigation. A compromise emerged: a group of scholars would examine the original journal under controlled circumstances. If they could verify authenticity, the committee would issue findings about its historical value.

Thomas agreed. In April 1864, he traveled to Detroit with five scholars, two congressional representatives, and a stenographer. They met at the bank, examining the journal in a private room with guards outside.

The examination was exhaustive. Dr. Philip Ashberry, a Harvard historian, analyzed the paper and ink. Professor John Whitfield, a linguist specializing in Arabic, examined the script and language. Dr. Rebecca Chen studied the handwriting, comparing it to known samples. For two days, they tested every aspect—binding, wear patterns, ink fading, cross-referencing entries with historical events.

On the evening of the second day, the scholars delivered their findings. “Gentlemen, we have examined this document as thoroughly as current methods allow. The paper is consistent with manufacturing techniques from the 1820s and 1830s. The ink matches formulations from that period. The Arabic script shows North African characteristics. The wear patterns and aging are consistent with a document handled carefully over decades.”

“What about the content?” a representative asked.

“The entries reference events and documents only recently rediscovered in archives,” Whitfield explained. “Information not accessible to the general public, certainly not to a seven-year-old in 1849. Some ships mentioned in the journal have verified existence through port records not widely available. The level of detail requires access to primary sources Mr. Freeman couldn’t have had as a child.”

Dr. Chen added, “The handwriting shows variation consistent with multiple writing sessions over time. Corrections, additions, changes in ink suggest it wasn’t created all at once. This is a journal compiled over time by someone with persistent access to confidential information. Everything indicates authenticity.”

The congressional representatives looked at each other. One, openly skeptical, spoke quietly. “So, you’re saying this is real? All of it?”

Ashberry replied, “We’re saying this journal was created in the period it claims by someone with extraordinary access to information about the slave trade, and its contents can be verified against independent historical sources. As a historical document—yes, it’s authentic.”

The news reached Washington within a week. The committee issued findings in May 1864: the journal was genuine, the documentation credible, the historical claims worthy of serious attention. They stopped short of calling for legal action—too much time had passed, and the war made such proceedings impractical. But they acknowledged the journal revealed disturbing patterns of fraud and systematic violation of human rights in the establishment of American slavery.

The scholars’ report changed everything. What had been controversial accusations became accepted historical fact. Families named in the journal could no longer simply deny the claims. They had to contend with verified documentation and scholarly consensus.

Some families responded by distancing themselves from ancestors’ actions, making donations to freedman schools and hospitals. Others retreated into denial, claiming the standards of the past couldn’t be judged by present morality. A few took more direct action. In June 1864, Thomas received a visitor—a well-dressed woman in her fifties, Katherine Harrington Sutherland, great-great-granddaughter of the merchant whose crimes were most thoroughly documented.

“I’ve come to apologize for what my ancestor did to yours,” she said. Thomas was stunned. He’d expected threats, legal challenges, or bribery—not this.

Mrs. Sutherland continued, “I’ve read your testimony, Miss Weston’s articles, and examined family papers never meant for outsiders. Everything you’ve claimed about William Creswell is true. He destroyed lives to build his fortune, and my family benefited for generations. I cannot undo what he did, but I can acknowledge it and try to make amends.” She placed a document on the table. “This is a legal instrument transferring property that’s been in my family since 1735, purchased with profits from the trade. I’m donating it for a school for freedmen. It’s not enough. It can never be enough. But it’s what I can do.”

Thomas looked at the document and Mrs. Sutherland. “Why?”

“Because the truth matters,” she said simply. “Because your mother was right to document what she witnessed, and you were right to preserve it. Because my children deserve to inherit something better than wealth built on lies and suffering.”

She left, and Thomas never saw her again. But her actions started something. Over the following months, other families made similar gestures—donations, public acknowledgments, small attempts at restitution.

Thomas remained in Boston through the end of the war, working with Harriet on additional research. Their work became foundational for a new generation of scholars studying the economic and legal structures of American slavery.

Epilogue: Legacy and Memory

When Lee surrendered at Appomattox in April 1865, Thomas was twenty-two. He attended the celebration in Boston Common, thinking of his mother, Marcus and Judith, Patient Hadley, and all who risked everything for truth. The war ended slavery as a legal institution, but not the racial hierarchy built to justify it. The families documented in the journal still held wealth and influence. The patterns of exploitation would find new forms, but the truth was now part of the historical record.

After the war, Thomas returned to Michigan, married Sarah Jenkins, and built a quiet life in Saginaw. They had four children, and Thomas taught each about the grandmother they’d never known. He never spoke publicly about the journal again, but continued to correspond with scholars and historians, helping connect the dots between documented crimes and their lasting consequences.

In 1891, Thomas donated the original journal to the Library of Congress, with instructions for its preservation and accessibility to researchers. The library agreed, and the journal found its final home in the manuscript division.

Thomas died in 1912, having lived long enough to see the promise of Reconstruction betrayed and Jim Crow laws establish new systems of oppression. His later letters show a man grappling with disappointment that the truth he’d helped reveal hadn’t transformed the country as much as he’d hoped, but he never regretted bringing the journal to light. The truth mattered, even when people chose to ignore it.

Harriet Weston continued her journalism until failing health forced retirement in 1887. She wrote dozens of articles and two books expanding on the research she’d done with Thomas, always crediting him as a collaborator and honoring his mother’s courage. When she died in 1889, Thomas traveled to Boston for her funeral, one of hundreds touched by her relentless commitment to truth and justice.

The stranger who purchased Thomas in Charleston remained an enigma. Despite decades of research, neither Thomas nor historians ever identified him. Some speculated he was an abolitionist working underground; others suggested he was a member of a secret society dedicated to preserving dangerous knowledge. Thomas believed the man had known exactly what the journal contained and recognized a child would be the safest guardian for such explosive information. But he never knew for certain, and the mystery became another thread in an extraordinary story.

Samuel Rutled, the auctioneer, died in 1873, having lost everything in the war. His auction house burned during Union occupation, and most records were destroyed. The single ledger page recording Thomas’s sale survived only because Rutled kept it separately, perhaps sensing even then that this transaction was different.

The families documented in the journal faced varying fates. Some acknowledged ancestral crimes and attempted restitution. Others fought the allegations, spending fortunes on lawyers and public relations campaigns that ultimately failed to erase the historical record. Several families disappeared from public life, their names vanishing from society registers.

By the early 1900s, Thomas Freeman’s story had become a legend in African-American communities—the child sold for $3 who helped expose the fraudulent foundations of slavery. The full details were largely forgotten by the broader public until the civil rights movement of the 1960s brought renewed interest in hidden histories.

In 1968, researchers at Howard University rediscovered the journal in the Library of Congress archives. They published the first complete translation, sparking new scholarship examining the economic and legal structures of slavery using Thomas’s mother’s documentation as a primary source. Thomas’s descendants, still living in Michigan, watched this renewed interest with mixed feelings—proud of their ancestor’s courage, but aware the work remained unfinished. The systems Thomas exposed had evolved, but hadn’t disappeared. The truth he helped preserve was still needed, still relevant, still challenging Americans to confront their history honestly.

The journal itself remains in the Library of Congress—its pages fragile but legible, available to researchers who make appointments to study it. Every few years, a new discovery emerges—a forgotten ledger entry, a faded letter, a connection no one noticed before. Piece by piece, the past begins to speak again.

News

Why US Pilots Called the Australian SAS The Saviors from Nowhere?

Phantoms in the Green Hell Prologue: The Fall The Vietnam War was a collision of worlds—high technology, roaring jets, and…

When the NVA Had Navy SEALs Cornered — But the Australia SAS Came from the Trees

Ghosts of Phuoc Tuy Prologue: The Jungle’s Silence Phuoc Tuy Province, 1968. The jungle didn’t echo—it swallowed every sound, turning…

What Happened When the Aussie SAS Sawed Their Rifles in Half — And Sh0cked the Navy SEALs

Sawed-Off: Lessons from the Jungle Prologue: The Hacksaw Moment I’d been in country for five months when I saw it…

When Green Berets Tried to Fight Like Australia SAS — And Got Left Behind

Ghost Lessons Prologue: Admiration It started with admiration. After several joint missions in the central Highlands of Vietnam, a team…

What Happens When A Seasoned US Colonel Witnesses Australian SAS Forces Operating In Vietnam?

The Equation of Shadows Prologue: Doctrine and Dust Colonel Howard Lancaster arrived in Vietnam with a clipboard, a chest full…

When MACV-SOG Borrowed An Australian SAS Scout In Vietnam – And Never Wanted To Return Him

Shadow in the Rain: The Legend of Corporal Briggs Prologue: A Disturbance in the Symphony The arrival of Corporal Calum…

End of content

No more pages to load