The Last Stand: John Wayne, The Shootist, and the Final Code of an American Legend

Part 1: The Heat of August

August 1976. Carson City, Nevada.

The barn was hot as hell. The kind of heat that made the wood sweat, that turned the dust to a fine powder, that made the air shimmer and the crew dream of ice water. It was the twelfth day of a twenty-three-day shoot, and inside that barn, John Wayne stood at the center of the storm.

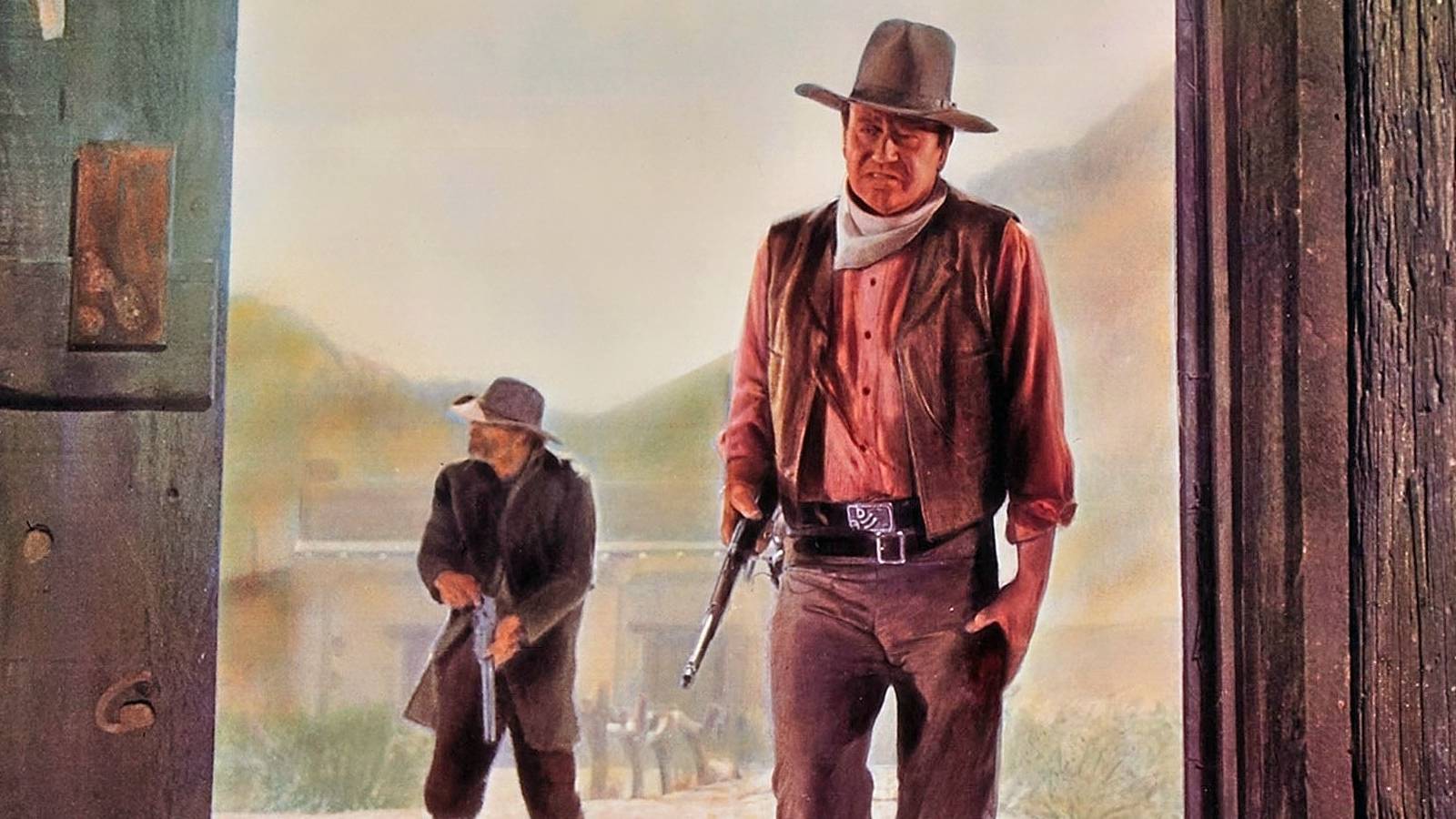

He wore a dark suit and vest, sweat running down his face, soaking the collar, tracing lines through the dust on his skin. At sixty-nine, Wayne was still a mountain—broad shoulders, heavy hands, a presence that filled every room, every set. But beneath the suit, beneath the legend, something else was happening. His stomach was a battlefield. Stage 4 cancer. Most men would be in a hospital, but Wayne was making a movie. His last movie.

The film was The Shootist, a Western about an aging gunfighter who finds out he’s dying of cancer and decides to go out on his own terms. Life imitating art, or maybe art imitating life. Either way, it hurt.

The director, Don Siegel, was a television man. Fast, efficient, demanding. He wanted options, wanted coverage, wanted eight to ten takes minimum for every scene. That was how TV worked—get everything, fix it in editing. But Wayne didn’t learn film from TV. He learned from John Ford. One take, maybe two. Trust the actor. Capture the moment raw and real.

Siegel called “Cut!” for the eighth time. Wayne had been standing for forty minutes. The pain in his stomach was constant now, sharp, like broken glass grinding with every breath. But he didn’t show it. He didn’t complain. He just waited for the next take.

Across from him stood James Stewart, sixty-eight, old friend. They’d known each other since the thirties. Stewart was playing the doctor who tells Books—the character Wayne played—that he’s dying. Ironic, because Wayne was actually dying, and nobody on set except his doctor knew.

Siegel was sixty-three, famous for directing Dirty Harry five years before. He came from television, where the rule was: get coverage. Wayne came from a different world. Two different schools, two different men, and they were starting to clash.

Part 2: The Clash of Generations and The Quiet Pain

This was not a typical John Wayne production. The budget was modest—just $2 million. Paramount Pictures was producing, and the script, based on Glendon Swarthout’s novel, was simple but strong. An aging gunfighter, facing death, chooses his own ending. Wayne read the script and knew: this was it. His last film. If he was going to say goodbye to Hollywood, he’d do it playing a man staring down the inevitable. At least he knew how that felt.

The cast was solid. Stewart, Lauren Bacall, Ron Howard—a young man who idolized Books. Good actors, no drama. Except with the director.

Siegel was intense, detail-oriented, relentless. He wanted perfection, wanted choices, wanted to shoot every scene from five different angles so he’d have options in the editing room. Wayne couldn’t stand it. One take, maybe two if something went wrong. Eight, nine, ten? That wasn’t filmmaking. That was television. And it was killing him—literally.

The first problem happened on day four. They were shooting a scene in Books’ boarding house room. Simple dialogue. Books talking to his landlady. Five pages of script. Should take one morning. Siegel wanted ten takes from three different angles—closeup, medium, wide.

By the sixth take, Wayne was leaning against the bedpost. Not because the character needed support, but because Wayne did. His legs were shaking. The pain in his stomach felt like someone was twisting a knife, but he didn’t say anything. Just kept going. Take after take.

Ron Howard watched from the corner. At twenty-two, he was already a seasoned actor, smart, observant. He could see something was wrong. Wayne’s face was gray, his breathing shallow. Between takes, Wayne’s hands gripped the bedpost so hard his knuckles turned white.

After the tenth take, Siegel finally said, “Print it.” Wayne walked to his trailer, didn’t talk to anyone, locked the door. Inside, there was an oxygen tank. His doctor had made him bring it. Wayne sat down, put the mask on, breathed, waited for the pain to ease. It didn’t.

Part 3: The Breaking Point and the Unspoken Battle

Day eight. They were filming outside, under the Nevada sun. The scene was simple—Books walking down the main street, horses and wagons and extras filling the background. The camera tracked alongside Wayne as he walked fifty yards. Siegel wanted four takes, different speeds, different expressions.

Wayne did the first take, made it halfway, stopped, bent over, hand on his knee, fighting for breath. The crew froze. Nobody moved, nobody spoke. Siegel called out from behind the camera, “Duke, you okay?” Wayne straightened up, waved him off. “Fine, let’s go again.”

They did the take again. Wayne made it to the end—barely. His face was pale, sweat soaking through his shirt despite the dry Nevada heat. Ron Howard stood near the camera, leaned over to the script supervisor and whispered, “Is he sick?” The script supervisor didn’t answer, but her expression said everything.

After the third take, Wayne walked to his trailer without a word. He stayed there for an hour. Siegel wanted to keep shooting, but the assistant director talked him out of it. “We can’t push him like this.” Siegel wasn’t happy, but he moved on to other shots.

Day eleven. The scene was heavy—Books visiting the doctor, Stewart’s character, who tells him he’s dying. Six weeks to live, maybe less. Wayne needed to show fear, anger, acceptance—all in three pages of dialogue.

Stewart was struggling. His hearing wasn’t good anymore. He was missing cues, starting his lines too early or too late, throwing off the rhythm. Siegel was getting frustrated. After the fifth take, he stopped Stewart mid-scene.

“Jimmy, you’re coming in too early. Wait for Duke’s line to finish.” Stewart looked embarrassed. “I’m sorry, I didn’t hear.” “Then listen closer.”

Wayne’s jaw tightened. He didn’t like the tone. Stewart was his friend, had been for forty years. You didn’t talk to him like that. Wayne stepped forward. “Don, he’s doing his best. Let’s just take it again.”

Siegel turned to Wayne. “Duke, we’re burning daylight. I need Jimmy to hit his marks.” “He will. Give him a minute.”

The set went quiet. Fifty crew members pretending to work while watching the tension between director and star. Siegel took a breath, nodded. “Okay, let’s reset.”

They did the take again. Stewart nailed it. Wayne nailed it. One take. Perfect. Siegel said, “Print it,” but didn’t look happy about being told to slow down. Wayne knew this wasn’t over. Knew they were building to something, but he was too tired to care.

Part 4: The Camera Confrontation and the Stand for Legacy

Day twelve. The barn scene.

Wayne and Stewart sat across from each other at a table. Books was asking the doctor to keep his illness quiet, not wanting the whole town to know he was dying. It was a simple scene—two actors, strong dialogue, should have been easy. But they’d been at it for ninety minutes, eight takes. Siegel wanted more coverage, different angles, tighter close-ups.

Wayne was exhausted. The pain was sharper, more constant. He was trying to breathe through it, trying to focus, but every take drained him more. Then he noticed the camera. It was positioned low, very low, ground level, pointing up at his face from below. The angle caught every wrinkle, every imperfection, his jowls, the loose skin under his chin.

Wayne had been in Hollywood for fifty years. He knew cameras, knew what worked and what didn’t. This angle was either incompetence or disrespect.

He stopped mid-scene, didn’t finish his line, just stood up. The barn went silent. Wayne walked over to the camera operator, pointed at the camera, then pointed up—signaling to move it higher. The operator looked at Siegel. Siegel shook his head. “Keep it there.” Wayne signaled again, more forceful. Nothing.

Then his voice, loud, cold, every syllable hard as stone: “Move the camera.”

Siegel walked over, trying to stay calm, professional. “Duke, this angle is—”

Wayne cut him off. “I don’t care what you learned in television. You don’t shoot John Wayne from the ground looking up. That’s not filmmaking. That’s embarrassment.”

Siegel’s face hardened. “It’s an artistic choice.”

“It’s a bad choice. Move it or I walk.”

The words hung in the air. Fifty crew members frozen. Cameras still rolling. Nobody breathed.

Wayne had never walked off a set in fifty years. Never. Everyone knew that. But they also knew he meant it. Siegel stared at him, calculating. This was John Wayne, the biggest star in Hollywood. Walk away and the movie died. The studio lost everything. Siegel’s career took a hit.

But it was more than that. Wayne wasn’t just protecting his vanity. He was protecting fifty years of carefully crafted presence. That face on screen meant something to millions. It represented strength, integrity, honor. Shooting him from the dirt looking up destroyed all of that.

Siegel finally spoke quietly. “Move the camera.”

The operator adjusted the angle. Higher. Eye level. Respectful.

Wayne walked back to his mark, sat down across from Stewart, waited for action. Siegel called action. Wayne delivered the scene. Perfect. One take, no mistakes. Then he stood up and walked off the set without a word. Straight to his trailer, locked the door.

Part 5: Lessons in the Trailer

That evening, Ron Howard knocked on Wayne’s trailer door. “Mr. Wayne?” Silence. “Mr. Wayne, can I ask you something?”

The door opened. Wayne was inside, still in costume, oxygen mask hanging around his neck. He looked exhausted, older than sixty-nine.

“What?”

Ron stepped inside, nervous. “Why did you get so angry about the camera?”

Wayne looked at him for a long time, then spoke slowly.

“Because that angle tells the audience I’m weak, old, pathetic.” He paused. “I’m not playing a pathetic man. I’m playing a strong man who’s dying. There’s a difference.”

Ron hesitated. “But you are dying. Everyone knows.”

Wayne’s eyes went hard. Not angry, just honest.

“Kid, I’ve spent fifty years showing America what a man looks like. Strong, capable, honorable. If my last image is me shot from the dirt looking up—” he shook his head. “That’s not how I go out. You understand?”

Ron nodded. “Yes, sir.”

“Good. Now, get some sleep. Tomorrow, we finish this picture.”

Part 6: Mutual Respect and The Final Wrap

The next day, something shifted. Siegel and Wayne didn’t speak directly, but Siegel adjusted. Fewer takes, better angles, more trust. He was still efficient, still professional, but he wasn’t pushing anymore. Wayne noticed, didn’t say anything, just did his work. They found a rhythm. Not friendship, but mutual respect.

Two weeks later, they wrapped production. Last day, last shot. Wayne delivered his final line on camera. The crew applauded, long and loud. Wayne took off his hat, nodded, walked to his trailer.

Siegel approached him at the wrap party that night, stood there holding a beer. Awkward.

“Duke, I’m sorry about the camera angle. I didn’t understand.”

Wayne looked at him, face unreadable. Then he spoke.

“You’re a good director, Don. You just don’t know cowboys yet.”

Pause.

“We don’t look up from the dirt. We die standing.”

Siegel nodded slowly. “I’ll remember that.”

They shook hands, firm, professional. Not friends, but not enemies either. Two men who clashed, who pushed each other, who made something great because they both refused to compromise on what mattered.

Part 7: Legacy

John Wayne died three years later, June 11, 1979. UCLA Medical Center. Stomach cancer finally won. He was seventy-two years old.

The Shootist became a masterpiece. Critics called it Wayne’s greatest performance—the role that showed the world he could actually act. Not just be John Wayne, but become someone else, someone real, someone dying.

Ron Howard went on to become one of Hollywood’s greatest directors—Apollo 13, A Beautiful Mind, Frost/Nixon, dozens of films. In 2004, he gave an interview to Vanity Fair about his early career, about learning from legends, and he told the story of that day in the barn.

“The Shootist taught me that how you’re seen matters. Duke fought for his image until his last breath. That wasn’t vanity. That was self-respect. He knew what he represented to millions of people, and he wasn’t going to let anyone take that away, not even at the end.”

Don Siegel directed five more films before retiring in 1982. He rarely talked about Wayne publicly. But in 1990, in an interview for a film school documentary, he admitted something.

“Wayne was right about that camera angle. I see it now. But he was too sick to explain why gently, so he had to be hard. Had to draw a line.”

Pause.

“I learned more from that one fight than I did in four years of film school. Sometimes protecting what matters means being willing to walk away from everything.”

Part 8: The Code

What did John Wayne protect? Not just his face, not just his legacy, but a code. The code of the American cowboy. Stand tall. Die standing. Show the world what strength looks like, even when you’re at your weakest.

Wayne’s last stand wasn’t a gunfight. It was a quiet moment in a hot barn, a battle over a camera angle, a fight for dignity. That’s how legends are made.

And that’s why, even now, people say: They don’t make men like John Wayne anymore.

News

John Wayne Refused A Sailor’s Autograph In 1941—Years Later He Showed Up At The Family’s Door

The Mirror and the Debt: A John Wayne Story Prologue: The Request San Diego Naval Base, October 1941. The air…

John Wayne Kept An Army Uniform For 38 Years That He Never Wore—What His Son Discovered was a secret

Five Days a Soldier: The Secret in John Wayne’s Closet Prologue: The Closet Newport Beach, California. June 1979. The house…

John Wayne- The Rosary He Carried in Secret for 15 Years

The Quiet Strength: John Wayne’s Final Keepsake Prologue: The Last Breath June 11th, 1979, UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles. The…

Young John Wayne Knocked Down John Ford in the Mud—What the Director Did Next Created a Legend

Mud and Feathers: The Making of John Wayne Prologue: The Forgotten Manuscript In 2013, a dusty box in a Newport…

John Wayne Helped This Homeless Veteran for Months—20 Years Later, The Truth Came Out

A Quiet Gift: John Wayne, A Forgotten Soldier, and the Night That Changed Everything Prologue: A Cold Night in Santa…

John Wayne Turned Down $1,000,000 — And Drew a Line Hollywood Couldn’t Cross

A Line in the Sand: John Wayne, Hollywood, and the Price of Principle Prologue: The Offer January 1968. Los Angeles….

End of content

No more pages to load