Always Rome: The Hidden Love of Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn

Prologue: The Eulogy

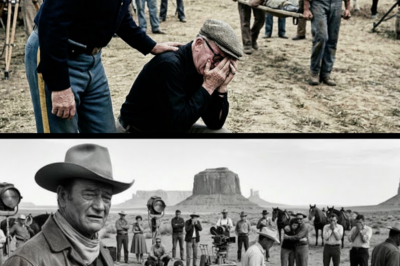

January 25, 1993. St. Martin of Tours Catholic Church, Brentwood, Los Angeles. The pews are packed—Hollywood royalty, international dignitaries, family, friends. Audrey Hepburn’s funeral is underway. At the podium stands Gregory Peck, 76 years old, distinguished, silver-haired, one of the last legends of Hollywood’s golden age.

He’s been asked to give the eulogy for his Roman Holiday co-star. His voice is steady at first, recalling Audrey’s grace, her kindness, her humanitarian work. The words are beautiful, appropriate, expected. Then, midsentence, something breaks. Peck’s voice cracks. He stops. His hands grip the podium. His eyes fill with tears. He tries to continue, but can’t. The church falls silent as Gregory Peck—famous for composure, strength, control—completely falls apart.

He sobs openly, grief so raw and overwhelming that even the seasoned mourners whisper. His wife, Veronique, sits in the front row, looking away. She knows. Everyone who knew Gregory Peck knows. This isn’t just grief for a friend. This isn’t mourning a co-star. This is a man who lost the love of his life 41 years ago and never recovered.

Finally, Peck manages to finish. His last words barely audible: “There will never be another like her.” He walks back to his seat, sits next to Veronique. She doesn’t touch him, doesn’t hold his hand. She understands something she’s known for 35 years of marriage. She was never the woman Gregory Peck truly loved. That woman just died, and her name was Audrey Hepburn.

Chapter 1: The Meeting

To understand what happened at that funeral, you have to go back to spring 1952, when everything started. Gregory Peck was already one of Hollywood’s biggest stars—nominated for multiple Academy Awards, admired by women, envied by men. He had the looks, the talent, the box office appeal. He was married to Greta Kukkonen, a Finnish woman he’d wed in 1942. They had three sons: Jonathan, Steven, and Carey. On paper, the perfect Hollywood family. In reality, the marriage was struggling. Peck worked constantly, gone for months at a time. The distance had created cracks, but divorce in 1950s Hollywood was career suicide. Studios had morality clauses. Divorced actors lost roles, endorsements, everything. So Peck stayed married, unhappily, waiting for something to change.

Then Audrey Hepburn walked into the audition. She was 23, unknown, thin, almost frail. Her features were unusual for Hollywood standards—not the bombshell type studios usually wanted. But when she read for the role, something magical happened. Director William Wyler saw it immediately. Producer screen tests confirmed it. This girl had something indefinable: grace, vulnerability, innocence mixed with intelligence. Wyler cast her as Princess Anne, Peck’s co-star. The film would rest on their chemistry. Nobody anticipated what that chemistry would become.

Chapter 2: Roman Holiday

Filming began in June 1952, Rome, Italy. The entire production shot on location—revolutionary for Hollywood at the time. The cast and crew lived in Rome for three months, away from studios, handlers, wives. The first day of shooting, Peck watched Audrey rehearse a scene. Years later, he described that moment diplomatically: “I knew immediately she was going to be a star.” But people on set tell a different story. They say Peck couldn’t take his eyes off her. That he watched her between takes. That even before they’d filmed a single scene together, he was already falling.

Audrey, for her part, was starstruck. Gregory Peck was Hollywood royalty—handsome, sophisticated, kind in a way male stars often weren’t. He treated her like an equal, not a nervous newcomer. He fought for her when Paramount tried to give him top billing alone, insisting her name appear equally with his. That gesture meant everything to Audrey. In Hollywood, where ego ruled, Peck was giving away billing to an unknown actress. It was unheard of, generous. And to Audrey, who’d spent her life feeling abandoned and dismissed, it felt like love.

But there was a problem. Actually, four problems: Peck’s wife, Greta, and their three sons waiting back in Los Angeles. Audrey knew Peck was married. Everyone did. Should have stopped there. Should have stayed professional. But Rome in summer has a way of making people forget the rules.

Chapter 3: The Affair

June 1952, Rome. The affair began quietly. So quietly that for the first few weeks, even the crew didn’t notice. Peck and Audrey would rehearse scenes after everyone else left. Have dinner together to discuss character motivation. Take walks through Rome to scout locations. All perfectly innocent explanations. Except they weren’t innocent. They were falling in love.

Costume designer Edith Head, who was on location for fittings, later told friends, “I knew within two weeks. The way he looked at her wasn’t acting. And Audrey, she was completely gone, head over heels.” The film required real chemistry—the story was about two people falling in love over 24 hours in Rome. Every scene had to crackle with attraction, with connection, with the feeling that these two people were meant to be together. That chemistry was easy, because it was real.

Watch Roman Holiday today. Watch the scene where Peck and Audrey ride a Vespa through Rome. Watch her arms wrapped around him. Watch his smile when she laughs. Watch the final scene at the embassy when Princess Anne and Joe Bradley say goodbye knowing they can never be together. That goodbye wasn’t acting. That was Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn breaking their own hearts on camera.

By mid-July, the affair was an open secret among the cast and crew. They’d see Peck leaving Audrey’s hotel room early in the morning, see them holding hands between takes when they thought nobody was watching, see the way they’d disappear during lunch breaks and return flushed, disheveled, obviously having done more than eat. Director William Wyler was pragmatic: “As long as it shows up on screen, I don’t care what they do off camera.” And it did show up on screen. The dailies were magical. The chemistry was undeniable.

Chapter 4: The Cost

Back in Los Angeles, Greta Kukkonen was reading gossip columns. Hollywood reporters were in Rome. They saw everything. And while they couldn’t print explicit details—studios controlled the press too tightly—they could hint. Gregory Peck and newcomer Audrey Hepburn seemed “quite close” on the Roman Holiday set.

Greta wasn’t stupid. She knew what “quite close” meant. She’d been married to Gregory for ten years. She knew when he was lying. When he called from Rome saying he missed her, saying filming was exhausting, but he couldn’t wait to come home, she heard the lie in his voice. In late July, Greta called the hotel in Rome directly. Asked to be connected to Gregory’s room. It was 3:00 a.m. Rome time. He didn’t answer. She called again 30 minutes later. Still no answer. She called Audrey’s room. Busy signal, phone off the hook. That was all Greta needed. The next day, she contacted her lawyer, started preparing divorce papers—not filing them, that would be too public, too damaging, but preparing. Greta wasn’t going to be humiliated by a 23-year-old actress who’d stolen her husband.

Meanwhile, in Rome, Peck and Audrey existed in a bubble. They talked about everything. He told her about his unhappy marriage, about feeling trapped, about how meeting her felt like waking up after years of sleepwalking. Audrey told him about her father abandoning her at age six, about the war years and starvation, about her desperate need to be loved and chosen, about how Peck made her feel safe in a way nobody ever had. They talked about the future—hypothetically, carefully. What if things were different? What if he weren’t married? Could they be together? Really together? Peck said yes. Absolutely yes. He’d leave Greta. He’d figure out custody arrangements with his sons. He’d face the studio consequences because Audrey was worth it. Worth everything.

Audrey wanted to believe him, but something held her back. A voice inside her, maybe her mother’s, maybe her own conscience, saying, “You don’t build happiness on someone else’s destruction.”

Chapter 5: The Goodbye

August 1952, filming wrapped. The cast and crew returned to Los Angeles. Peck went home to Greta and his sons. Audrey checked into a small apartment in West Hollywood. They promised to talk, to figure things out, to find a way. But reality hit fast.

Greta confronted Gregory the day he returned. “Are you in love with her?” she asked. Not, “Did you sleep with her?” Not, “Did you have an affair?” Just, “Are you in love?” Gregory Peck, a man famous for his integrity, his honesty, couldn’t lie. “Yes,” he said. “I am.”

Greta’s response was calm, cold, calculating. “Then you have a choice. File for divorce and destroy your career, or end it with her and keep everything.” She knew Hollywood’s rules, knew the studios wouldn’t tolerate a divorce scandal, especially not one where a major star left his wife and three children for a younger actress. The morality clauses in Peck’s contracts were ironclad. If he divorced Greta for Audrey, he’d lose millions, lose roles, possibly lose everything.

Peck tried to argue, said they could make it work, that his career would survive, that love mattered more than money. Greta laughed. “Ask Ingrid Bergman how her career is going,” she said. Bergman had left her husband for Italian director Roberto Rossellini in 1950. Hollywood blacklisted her, destroyed her reputation. She couldn’t work in America for seven years. That was the price of breaking the rules.

Gregory Peck faced an impossible choice: his career and family, or Audrey.

Chapter 6: The Decision

September 1952, Los Angeles. Gregory Peck sat in his study. Greta had given him one week to decide—divorce her and face the consequences or end it with Audrey and stay married. He was leaning toward divorce. He’d already contacted a lawyer quietly, started discussing terms. He was willing to pay, willing to lose, because he believed Audrey was worth it.

Then he called Audrey, told her he was ready—ready to leave Greta, ready to fight for them. Her response shocked him. “No,” she said quietly.

“What do you mean?” Peck asked.

“I want to be with you. I love you.”

“I love you, too,” Audrey said. “But I won’t be the woman who destroys a family. I won’t be the reason your sons grow up without their father. I can’t live with that.”

Peck tried to convince her his marriage was already broken. The divorce would happen eventually anyway. She wasn’t destroying anything, just accelerating the inevitable. But Audrey was firm. She’d grown up without a father. She knew what abandonment felt like. She wouldn’t do that to Peck’s sons. Not for anything. Not even for love.

“I need you to go back to Greta,” Audrey said. Her voice was breaking. “Try to make it work for your children, please.”

This is where Audrey’s wound shows. Her father abandonment trauma was so deep that she gave up the man she loved to protect his children from experiencing what she’d experienced. She chose their pain over her happiness.

Peck was devastated. “This is your decision?” he asked. “You’re ending this.”

“I have to,” Audrey whispered, then hung up.

For three days, Peck didn’t call her back, didn’t contact her. He sat in his house drinking, trying to figure out what to do. Part of him wanted to ignore Audrey’s wishes, show up at her door, convince her they could make it work. But another part knew she was right. The scandal would be massive. His sons would be hurt. His career would suffer. And Audrey, 23 years old, just starting out, would be labeled a homewrecker. Hollywood would destroy her before she even got started.

So Gregory Peck made his choice. He stayed with Greta, told his lawyer to stop the divorce proceedings, told the studio everything was fine, told his friends the affair was over. But he couldn’t stop loving Audrey. That part was impossible.

Chapter 7: Roman Holiday Premiere

August 27, 1953, Roman Holiday premieres in New York City. It’s been a year since filming wrapped. A year since Peck and Audrey ended their affair. In that year, both their lives changed dramatically.

Audrey’s career exploded. Roman Holiday made her an instant star. The critics raved. Audiences loved her. She was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress. At 24 years old, for her first major role, she’d moved on romantically, or tried to. She met actor Mel Ferrer in late 1953. He was older, sophisticated, controlling, but he wanted to marry her. And Audrey, still heartbroken over Peck, said yes—because being alone hurt more than being with the wrong person.

Peck was still married to Greta, but the marriage was dead. They lived in the same house but barely spoke. Slept in separate bedrooms, kept up appearances for the press. But behind closed doors, they were strangers.

At the Roman Holiday premiere, Peck and Audrey saw each other for the first time since the affair ended. He arrived with Greta. Audrey arrived with her mother. They sat in different sections of the theater. When the lights went down and the film began, everyone in that theater watched one of the most romantic movies ever made. They watched Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn fall in love on screen. Watch them ride through Rome. Watch them dance. Watch them say goodbye at the embassy in that heartbreaking final scene. And everyone knew—the emotion on screen was real. The chemistry was real. This wasn’t acting. This was two people who loved each other and couldn’t be together.

When the film ended, the applause was thunderous. Standing ovation. Audrey’s performance was flawless. The reviews the next day would confirm what everyone suspected. She was going to win the Oscar.

At the afterparty, Peck and Audrey were kept separate by handlers. Studios didn’t want them photographed together. Too many rumors already. But late in the evening, they found themselves alone in a hallway.

“You were brilliant,” Peck said. “You’re going to win.”

“You were wonderful, too,” Audrey replied. She was trying to stay composed, professional, but seeing him hurt. Being this close hurt.

“I’ve missed you,” Peck said quietly.

“Greg, please don’t. I made a mistake. Staying with Greta. I should have fought for us.”

“You made the right choice,” Audrey said firmly. “For your sons, that’s what matters.”

“And what about us? What about what we wanted?”

Audrey looked at him, her eyes filled with tears. “Sometimes what we want doesn’t matter. Sometimes we have to choose what’s right over what feels good.”

Then she walked away. Back to the party. Back to smiling for cameras. Back to pretending her heart wasn’t breaking.

That was the last real conversation they had for 40 years.

Chapter 8: Separate Lives, Shared Longing

-

Audrey wins the Academy Award for Best Actress. Roman Holiday makes her a global icon. She marries Mel Ferrer in September. The marriage will be hell—14 years of psychological abuse.

Gregory Peck’s marriage to Greta continues deteriorating, but they don’t divorce. Not yet. The studio pressure is too intense.

1955, Greta finally files for divorce after 13 years of marriage. The official reason: irreconcilable differences. The real reason: Gregory Peck never stopped loving Audrey Hepburn. The divorce is finalized. Peck pays substantial alimony, gets joint custody of his sons. His career survives, barely, but he’s lost years and he’s lost Audrey.

1956, Peck meets Veronique Passani, a French journalist. She’s beautiful, intelligent, kind. They marry in December 1955. Everyone says he’s moved on, found happiness. But Veronique knows the truth from day one. She knows about Audrey, about the affair, about the love that never died. And she makes peace with it, because the alternative is losing Gregory.

1968, Audrey finally escapes Mel Ferrer. Files for divorce after 14 years of hell. She’s broken, damaged, but free. Gregory Peck hears the news. For a moment, just a moment, he considers reaching out, but he’s married to Veronique. Has been for 13 years. He can’t destroy another marriage. Not again.

1969, Audrey marries Andrea Dotti, an Italian psychiatrist. The marriage is better than Mel’s—at least Dotti doesn’t abuse her psychologically, but he cheats constantly. 200 affairs over 13 years. Audrey tolerates it because she’d rather be unhappy than alone.

1980, Audrey meets Robert Wolders. Finally, finally, finds real love. Healthy love. They live together but never marry. She’s learned legal papers don’t guarantee anything.

Through all of this, Gregory Peck watches from a distance. He reads about Audrey’s marriages, her divorces, her struggles, and he wonders, “What if I’d fought for her? What if I’d chosen differently?”

Chapter 9: The Final Goodbye

1992, Audrey is diagnosed with appendix cancer. November, she’s 63 years old. The prognosis is grim—months, maybe weeks. Gregory Peck hears the news. He’s 76 now, still married to Veronique, but he sends flowers, writes a note. “Thinking of you always, Greg.” Audrey receives it, reads it, cries, tells Robert Wolders, “He was the first man who made me feel beautiful. Really beautiful. Not because of how I looked, because of who I was.”

January 20, 1993. 2:00 a.m. Audrey Hepburn dies in her Swiss villa. Robert Wolders holding her hand. Her sons nearby. Gregory Peck hears the news that morning. He’s in Los Angeles. Gets the call from Audrey’s publicist. Asked to give the eulogy. He says yes immediately. Veronique watches him hang up the phone, watches him sit down, watches him cry. She doesn’t say anything, doesn’t comfort him, because she knows—this is the grief of losing the woman he truly loved. And she can’t compete with that ghost.

January 25, 1993. Five days after Audrey’s death, St. Martin of Tours Catholic Church, Los Angeles. Gregory Peck stands at the podium. He’s prepared a speech, typed notes, beautiful words about Audrey’s grace, her talent, her humanitarian work. But when he starts speaking, the notes don’t matter. All he can think about is Rome. Summer 1952, riding a Vespa through cobblestone streets, Audrey’s arms wrapped around him, her laugh in his ear, the feeling that he’d finally found the person he was meant to be with. And then choosing wrong, choosing safety over love, staying with Greta instead of fighting for Audrey, spending 41 years wondering what if.

Mid-eulogy, his voice cracks. He tries to continue. Can’t. The grief is overwhelming. Not just grief for Audrey’s death. Grief for what they never had. For 41 years of separation, for a love that never got its chance. He’s sobbing now in front of 2,000 people, in front of his wife, in front of cameras that will broadcast this moment worldwide. Finally, he manages to finish. “There will never be another like her.” He walks back to his seat, sits next to Veronique. She doesn’t touch him, doesn’t hold his hand because she understands. She was never Gregory Peck’s great love. She was the consolation prize, the woman he married because he couldn’t have the woman he wanted.

After the funeral, at the reception, multiple people approach Peck offering condolences, saying how moving his eulogy was, how clear it was that he loved Audrey. One person, an old friend from the Roman Holiday set, says quietly, “You should have fought for her, Greg. You should have fought.” Peck doesn’t respond because what can he say? He knows it’s true.

Chapter 10: Epilogue

2003, ten years after Audrey’s death, Gregory Peck dies, age 87. Cause: bronchopneumonia. In his final weeks, bedridden, barely conscious, he talks about Audrey. Veronique sits beside him, listening to her husband of 48 years confess that he never stopped loving another woman. His last clear sentence two days before death: “I should have gone with her to Rome. I should have stayed.”

Veronique understands. He’s not talking about physical Rome. He’s talking about choosing Audrey, choosing the life they could have had.

Gregory Peck is buried in Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, Los Angeles. At his funeral, Veronique makes a request: “Please don’t mention Audrey. He’s with me now.” But everyone knows the love of Gregory Peck’s life wasn’t Veronique. It was Audrey. And 41 years of separation didn’t change that.

Summer 1952, Rome. Two people fall in love while making a movie about two people who fall in love and can’t be together. The movie ends with goodbye. The princess returns to her royal duties. The journalist goes back to his life. They’ll never see each other again, but they’ll always have Rome.

Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn lived that ending, except their goodbye lasted 41 years. From September 1952 to January 1993. Forty-one years of separate lives, different spouses, different paths. But the love never died.

Audrey kept it private. She rarely spoke about Peck publicly, but friends knew. Robert Wolders knew. When she watched Roman Holiday, she’d cry at the ending every time. Gregory Peck couldn’t hide it. His wife knew. His friends knew. And when Audrey died, the entire world saw it. Saw him break down at her funeral. Saw the grief of a man who’d lost his chance 41 years earlier and never recovered.

This is what happens when you choose safety over love. When you stay in the wrong relationship because leaving is too hard. When you let fear make your decisions. Gregory Peck chose his career and his children over Audrey. Noble choice? Maybe. Right choice? Depends who you ask. His sons got to grow up with their father. His career survived. He lived to 87, married to Veronique for 48 years. But he died loving Audrey Hepburn. Died wishing he’d chosen differently. Died knowing he’d let the great love of his life walk away.

Audrey chose to let him go. Chose to protect his children from the pain she’d experienced. Noble choice. Absolutely. Right choice? Also depends who you ask. She got to keep her conscience clear. Got to know she hadn’t destroyed a family. Got to eventually find real love with Robert Wolders. But she died without ever telling Gregory Peck what his note meant to her. Died without saying, “Yes, I never stopped loving you either.”

Roman Holiday ends with Princess Anne and Joe Bradley in a room full of reporters. She’s answering questions. He’s watching from the back. They make eye contact. She says her favorite city was Rome. He understands. They’ll always have Rome.

Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn had Rome, too. Summer 1952. Three months of filming. Three months of love. Then 41 years of wondering what if. The movie is beautiful. The love was real. The ending was tragic. And sometimes, even when you make the right choice, you spend the rest of your life regretting it.

News

Tragedy in the Alps: Caitlin Clark’s Uncle Among Victims of Deadly Crans-Montana New Year’s Eve Explosion in…

Tragedy in the Alps: The Night the Stars Fell Part 1: Celebration and Shadows Crans-Montana, Switzerland. December 31, 2025. The…

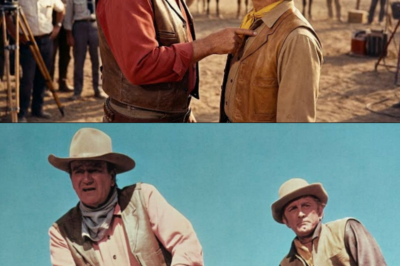

John Wayne Asked Frank Sinatra to Be Quiet Three Times- But His Responde Was Unacceptable

The Night the Legends Collided Part 1: The Sands Hotel, Las Vegas, June 1966 The neon lights of Las Vegas…

A Stuntman Died On John Wayne’s Set—What He Did For The Widow Nobody Knew For 40 Years

The Fall: A True Hollywood Story Part 1: The Morning Ride December 5th, 1958. Nachitoches, Louisiana. The sun rose slow…

John Wayne’s Final Stand Against His Director – The Last Days of a Legend

The Last Stand: John Wayne, The Shootist, and the Final Code of an American Legend Part 1: The Heat of…

When Kirk Douglas Showed Up Late, John Wayne’s Revenge Sh0cked Everyone

War Wagon Dawn: John Wayne, Kirk Douglas, and the Desert Duel That Changed Hollywood Part 1: The Desert Standoff September…

Marlene Dietrich Saw Wayne and Said ‘Daddy, Buy Me That’ – What Happened Next Destroyed His Marriage

When Legends Collide: John Wayne, Marlene Dietrich, and Hollywood’s Most Dangerous Affair Part 1: The Glance That Changed Everything Spring,…

End of content

No more pages to load