The Fall: A True Hollywood Story

Part 1: The Morning Ride

December 5th, 1958. Nachitoches, Louisiana.

The sun rose slow over the set of The Horse Soldiers, painting the dirt roads and wooden structures gold. It was early, the kind of quiet only found before a day of chaos. Crew members hauled cables and lights, costume girls fussed with buttons and hats, wranglers led horses to water troughs. The set, built to mimic Civil War-era Mississippi, buzzed with the energy of a big-budget Hollywood epic.

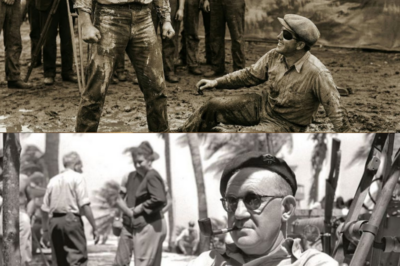

Director John Ford stood near the main street, his megaphone in hand, surveying the scene. Ford was a legend—gruff, brilliant, unpredictable. He’d made stars out of men like John Wayne and William Holden, and today, both were on set, suited up and ready for battle scenes. There would be cavalry charges, clouds of dust, rifles loaded with blanks, and the kind of authenticity Ford demanded from every frame.

But before the main actors arrived, before the cameras rolled for the big moments, one man showed up early. Fred Kennedy. Forty-nine years old, two decades in the business, a veteran stuntman with a quiet demeanor and an athletic build. Fred was the kind of man directors trusted with their most dangerous work. He’d worked on every John Ford film for the past decade—Rio Grande, The Searchers, Hondo, The Quiet Man, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon. Ford knew him. Wayne knew him. Fred was a familiar face, always there, never complaining, just doing the work.

That day, Fred had a simple assignment: a saddle fall. Ride hard, take the hit, tumble from the horse. He’d done it hundreds of times. Routine work, standard stunt. He needed the extra money, so he accepted.

By midday, the battle scene was ready. Confederate cavalry lined up opposite Union soldiers. Horses pawed the ground, smoke machines hissed, dust hung in the air. Ford barked orders, cameras found their angles, reflectors caught the sun. John Wayne waited off to the side, full costume, makeup done, his scene scheduled later. He watched the prep, saw Fred mount his horse in the distance—silent, professional, a man who knew his job.

They’d worked together on seven films. Wayne recognized the routine. Fred was always steady, dependable, never asking for attention, just getting it done.

Part 2: The Stunt, The Fall, and The Silence

Noon approached. The Louisiana sun grew stronger, but the air still held a winter chill. Ford lifted his megaphone, his voice echoing across the set. “Let’s get ready! Cameras up! Constance, you’re on your mark!”

Actress Constance Towers took her place near the action. Her role in this moment was simple: after Fred’s fall, she would run to him, cradle him, and deliver her line. A moment of tenderness in the chaos of battle.

Fred waited one hundred yards back on his horse, steady in the saddle. The scene was simple. Ride forward at a full gallop, take the hit, fall from the saddle. It was a standard cavalry stunt—one Fred had done harder versions of many times before. There was a small campfire burning near the camera setup, a set decoration meant to add realism to the battle scene.

Ford checked his watch. “Quiet on set!” Silence settled over the field. The only sounds were the shuffling of horses and the distant caw of a crow.

“Action!”

Fred spurred his horse forward. The animal launched into a gallop, hooves pounding the dirt. Cameras rolled. Forty crew members watched. The horse approached the campfire, hesitated. The flames spooked it just slightly, enough to shift its trajectory. Fred adjusted, tried to compensate, but the momentum was wrong, the angle off.

The fall began.

Fred left the saddle, airborne. But something was different. The rotation wasn’t right. He was missing the safety equipment he normally used—the stirrup step that helped control the fall. He hit the ground head first.

Thud.

The sound carried across the set. Ford shouted, “Cut!”

The set froze. Fred lay motionless in the dirt, face down, not moving. Nobody panicked yet. Stunt falls sometimes looked like this—the stillness, the moment before the stuntman got up, dusted himself off, asked for another take.

Constance Towers entered the scene, as scripted. She ran to Fred, dropped to her knees, lifted him into her arms, ready to deliver her line. “My darling—” she began. But something was wrong. Fred wasn’t responding. His weight felt different. Dead weight. No breath. No movement.

Constance’s expression changed. The script fell away.

“Fred?” Nothing.

“Fred!” Her voice cracked. “Somebody help!”

The set erupted. Crew members rushed from every direction, running, shouting. John Ford reached Fred first, dropped to his knees, touched Fred’s neck, checked for a pulse. His eyes closed.

John Wayne sprinted across the lot. Fifty people formed a circle around Fred’s body, shock on every face. Someone yelled, “Get a doctor!” Another voice: “Call an ambulance!”

Constance Towers remained on the ground, Fred’s head cradled in her lap. Blood on her costume. Tears streaming, hands shaking.

The medic arrived, knelt, examined Fred’s neck. Broken. No breath. “We need to get him to a hospital now.”

A pickup truck backed up to the scene. Crew members lifted Fred carefully, slowly placed him in the truck bed. Ford watched, frozen, face drained of color, unable to speak. Wayne stood beside him, hand on Ford’s shoulder, silent.

The truck pulled away, dust rising behind it. Constance Towers sat in the dirt, crying. Forty crew members stood motionless. Nobody spoke, just the wind.

Part 3: Grief, Guilt, and the Night That Followed

Thirty minutes passed. The set was silent except for the wind rattling through the trees and the distant hum of the pickup truck carrying Fred away. Crew members stood in small groups, heads bowed, some crying openly, others just staring at the spot where Fred had fallen.

A radio crackled. The message came through: DOA. Dead on arrival. Fred was gone. Forty-nine years old.

John Ford collapsed, sitting hard in the dirt, his head in his hands. John Wayne stood beside him, watching, saying nothing. There was nothing to say. Constance Towers sat in shock, trembling, staring at nothing. The rest of the crew waited, uncertain, lost.

Ten minutes passed before Ford finally stood, slow and unsteady. He looked at his crew—fifty faces watching, waiting for direction. He picked up his megaphone, his voice shaking.

“Listen up,” he said. Everyone turned, the sound of his voice cutting through the grief. “We’re shutting down. Pack everything. We’re going back to Hollywood.”

Murmurs rippled through the crowd. Production would move to California. They would finish there. Nobody argued, nobody questioned. Ford dropped the megaphone, walked to his trailer, closed the door behind him. Wayne watched him go, then turned to help with the packing.

The set began to dismantle. Equipment was packed, horses loaded into trailers, costumes folded and boxed. Louisiana filming was over. Fred’s blood still stained the dirt.

That night, nobody talked. Crew members returned to their hotel rooms in silence. Wayne sat alone in his room, unable to sleep. He kept seeing it—the fall, the sound, the thud, Constance’s scream echoing in his mind.

At 11 p.m., Wayne got up, walked down the hall to Ford’s room, and knocked. Ford opened the door, eyes red and swollen. “Duke,” he said in a hoarse whisper.

“Pappy, can I come in?”

Ford nodded, stepping aside. The room was dark, lit only by a single lamp. Ford sat at the table, an empty glass in front of him. Wayne sat across from him. Long silence.

Ford spoke first, his voice quiet and broken. “I killed him.”

Wayne shook his head. “Pappy, it was an accident.”

“I asked him to do it. He needed the money. I knew that.”

Wayne listened as Ford continued, his words punctuated by regret and pain. “Fred loved horses. You know that. He trained falling horses. Humane methods, after SPCA came down on Hollywood. He developed techniques that kept the animals safe. He had a family—wife, three kids, mortgage on a house. He was always working, extra gigs, extra stunts, anything to make ends meet.”

Ford’s voice broke. “He asked me for extra work last week. I said yes. I thought I was helping.”

Wayne tried to reassure him. “You were helping.”

Ford shook his head. “No, I was using him. He was broke. I knew he couldn’t say no.”

The empty glass sat between them. Wayne saw the whiskey bottle on the table, untouched. He knew Ford was on a diet, doctor’s orders—no alcohol. Ford had even banned drinking on set for everyone. But tonight, Wayne reached for the bottle, poured two glasses, and slid one to Ford. Ford took it without hesitation.

They drank. No words.

Ford finally whispered, “He was my friend, Duke. Twenty years. And I sent him to his death.”

Wayne had no answer. There was no answer. They sat, they drank, and they talked until dawn. About Fred, about horses, about his family, his kids, his dreams—a man who wanted a yard for his children, a man who was gone now.

Part 4: Hollywood, the Editing Room, and Ford’s Penitence

Weeks passed. The production moved to Hollywood, San Fernando Valley. The final battle scenes were filmed again, but something fundamental had changed. Ford’s direction was different—less passion, less fire. The original script had called for a triumphant arrival in Baton Rouge, celebration, crowds, victory. Ford scrapped it. The new ending was abrupt: a bridge explosion, a quick finish. Done. He’d lost interest, or maybe the pain was simply too much. He just wanted it finished.

In the editing room, Ford sat hunched over the reels, watching the Louisiana footage. Fred’s fall played on the screen—the real death, captured on film. The assistant editor hesitated, voice soft: “Do we cut this scene, Mr. Ford?”

Ford stared at the screen, eyes unreadable. He watched Fred fall one more time.

“Keep it, sir. Keep it in the film. Fred was a professional. The scene stays.”

The editor said nothing, just nodded. Days later, Wayne learned about the decision. He went to the editing room.

“Pappy, you’re keeping Fred’s scene?”

Ford didn’t look away from the screen. “He died doing his job. The scene stays.”

Wayne didn’t argue. He understood. This was Ford’s penance. Every time someone watched the film, Fred would die again—forever. Ford’s reminder, his burden.

The Horse Soldiers released in 1959. There was no press coverage of Fred’s death. The studio buried it, not wanting scandal. The Los Angeles Times ran a small obituary—one paragraph, that’s all. Fred was laid to rest at Valhalla Memorial Park in North Hollywood. The service was small: family, a few friends, no Hollywood crowd, no press. A quiet goodbye.

The film flopped at the box office. Critics called it lackluster and pointed to the abrupt ending. Nobody knew why Ford changed it, but Fred’s scene remained. Millions watched it—the man falling from the horse, the real death—and they had no idea.

Part 5: Wayne’s Quiet Act and the Years After

But what John Wayne did next, nobody expected. Months after the accident, Wayne sat in his office, staring at the wall. He called his assistant.

“Can you get me Fred’s home address?”

The assistant looked surprised, but didn’t ask questions. The next day, the address arrived. Wayne drove alone, telling no one where he was going. As he drove, Ford’s words echoed in his mind—mortgage, three kids, he needed the money.

Burbank. A modest neighborhood. Tree-lined streets, small houses. Wayne found the address, parked, and walked to the front door. He knocked.

The door opened. A young woman, mid-thirties, tired eyes. She saw Wayne and froze.

“Mr. Wayne.”

“Ma’am, I was Fred’s friend. May I come in?”

She was in shock, but stepped back immediately. “Of course, please.”

Inside, the furniture was modest, clean but worn. Family photos lined the walls. Three children sat quietly in the living room. The youngest, a little girl, stared at a framed photograph of her father. Wayne saw her, and his chest tightened.

They sat. The woman made coffee, her hands shaking as she poured.

Wayne said, “I wanted to pay my respects. Fred was… he was a good man.”

“Thank you, Mr. Wayne. Fred admired you so much. He always talked about working with you.”

They talked about Fred—memories, the horses he loved, the stunts he’d perfected. The woman smiled sometimes, cried sometimes. Fifteen minutes passed, then Wayne shifted the conversation, careful, gentle.

“How are you managing?”

She hesitated. “The studio… they sent some money. It helps.”

Wayne said nothing.

She continued, voice soft, “Fred always wanted a house with a yard for the kids. We got a mortgage. He said, ‘Five more years of work and we’d pay it off. Then he could retire. Just be home.’” Her voice broke. “He was so close.”

Wayne sat quiet. Inside, anger burned. He knew what the studio paid—enough for five, maybe six months of mortgage payments and living expenses. After that, nothing. But his face showed nothing.

Wayne spoke, calm and steady. “Ma’am, I want to help with your mortgage.”

She stared. “Mr. Wayne, I… I can’t accept that.”

“Yes, you can. Fred worked with me for years. He was my friend.”

“But it’s too much. I couldn’t.”

“Fred would want his family in this house, safe, secure. Let me do this, please.”

Long silence. Tears streamed down her face. She nodded.

“Thank you. Thank you, Mr. Wayne.”

Wayne stood. “Someone will bring something by in a few days.” She reached to shake his hand. Wayne pulled her into a brief embrace instead.

“Take care of those kids.”

He left, got in his car, looked at himself in the rearview mirror. For the first time in months, something loosened in his chest. Not relief, not redemption, just something. He did one thing for Fred—small, but real.

A few days later, an assistant delivered a sealed envelope to the address. Inside, a check—the remaining mortgage balance, plus a little extra. Fred’s family was saved.

Wayne never mentioned it. Not to Ford. Not to anyone.

Part 6: Legacy and Remembrance

The years passed. 1973. John Ford died at seventy-nine. He never forgave himself for Fred.

-

John Wayne died at seventy-two. He never forgot that day in Louisiana.

1980s. Fred’s youngest daughter was grown now. One afternoon, talking with friends, the conversation turned to old Hollywood. She mentioned it casually.

“John Wayne came to our house after my dad died. He helped us with the mortgage. We didn’t know at the time, but…”

Her friends stared. “John Wayne? Seriously?”

“My mom told me years later. Made me promise not to tell anyone while he was alive. He didn’t want attention.”

-

The Hollywood Stuntman’s Hall of Fame inducted Fred—twenty-four years after his death.

Today, The Horse Soldiers remains available. Fred’s death scene is still in the film. Every person who watches it sees him fall, sees him die—real footage, real death. Most have no idea.

Valhalla Memorial Park, North Hollywood. Fred’s grave rests under a simple stone.

Fred Kennedy

1909 – 1958

Beloved father and friend.

Simple, quiet, a life remembered.

Fred died for extra money. John Ford never forgave himself. John Wayne helped in silence, asked for nothing, told no one. And Hollywood buried it. Fred’s fall remains in the film—real footage, real death. Ford kept it as penance, a reminder every time someone watches. Wayne paid off the mortgage, told nobody.

Because real heroes help quietly. No cameras, no applause. Just doing what’s right when nobody’s watching.

Fred wasn’t just a stunt man. He was a father, a husband, a friend, a man who loved horses and wanted a yard for his kids. And when he died, two legends never forgot him. One lived with guilt. The other helped in silence.

If you were in Wayne’s position, would you have helped Fred’s family in secret?

Let me know in the comments below.

And unfortunately, they don’t make men like John Wayne anymore.

News

John Wayne Drop A Photo And A Night Nurse Saw It—The 30 Faces He Could Never Forget

The Faces in the Drawer: John Wayne’s Final Debt Prologue: The Ritual UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, May 1979. The…

John Wayne Refused A Sailor’s Autograph In 1941—Years Later He Showed Up At The Family’s Door

The Mirror and the Debt: A John Wayne Story Prologue: The Request San Diego Naval Base, October 1941. The air…

John Wayne Kept An Army Uniform For 38 Years That He Never Wore—What His Son Discovered was a secret

Five Days a Soldier: The Secret in John Wayne’s Closet Prologue: The Closet Newport Beach, California. June 1979. The house…

John Wayne- The Rosary He Carried in Secret for 15 Years

The Quiet Strength: John Wayne’s Final Keepsake Prologue: The Last Breath June 11th, 1979, UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles. The…

Young John Wayne Knocked Down John Ford in the Mud—What the Director Did Next Created a Legend

Mud and Feathers: The Making of John Wayne Prologue: The Forgotten Manuscript In 2013, a dusty box in a Newport…

John Wayne Helped This Homeless Veteran for Months—20 Years Later, The Truth Came Out

A Quiet Gift: John Wayne, A Forgotten Soldier, and the Night That Changed Everything Prologue: A Cold Night in Santa…

End of content

No more pages to load