On June 8, 2014, 52-year-old Johann Westhauser, a seasoned physicist and veteran cave explorer, lowered himself into the gaping mouth of the Riesending — German for “the Giant Hole.”

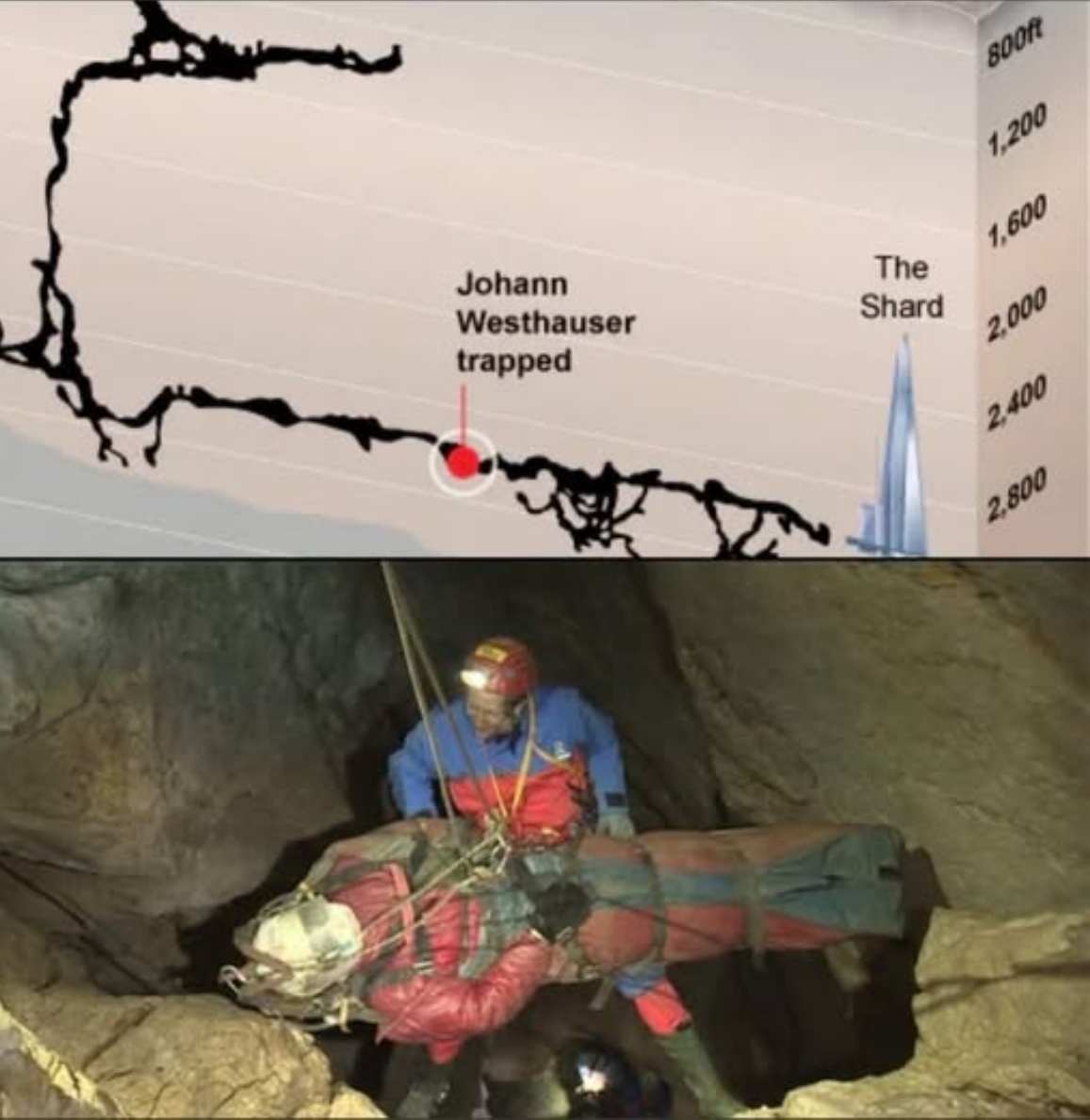

It wasn’t his first time exploring the cave. Stretching nearly 12 kilometers into the Berchtesgaden Alps, the Riesending is a frozen labyrinth of vertical shafts and tunnels. It’s a place where daylight dies after the first hundred feet, and silence hums in your ears like static.

For Johann and his two teammates, this was supposed to be another scientific mapping mission. They were equipped with helmets, ropes, carbide lamps — and years of experience. What they didn’t know was that this descent would turn into one of the most extraordinary survival stories in modern history.

Deep inside the mountain — 3,000 feet down — the air grows colder, thinner. Every movement echoes off the wet limestone walls. Then, somewhere between two vertical shafts, it happened.

A rock — no larger than a melon — broke loose from the ceiling.

It struck Johann squarely on the head.

The blow fractured his skull. Blood pooled under his helmet. His light flickered out.

Panic surged through the team. In that darkness, the two other explorers — both trained cavers — faced an impossible decision: stay or go.

One chose to remain behind, tending to Johann, whispering words of encouragement as he drifted in and out of consciousness. The other began the longest, most dangerous climb of his life — a 12-hour vertical ascent through freezing shafts and slick rock to reach the surface and raise the alarm.

By the time rescuers received the call, Johann had been trapped for nearly a day. His injuries were severe — a skull fracture deep underground meant time was not on their side.

Still, the Germans responded with precision. Within hours, more than 700 rescue workers from across Europe mobilized. Paramedics, cavers, engineers, and soldiers converged on the mountain. Helicopters thundered overhead, dropping tons of equipment into the narrow alpine valley.

This was to become the largest cave rescue in German history.

Rescuers faced challenges that bordered on impossible:

Narrow passages — Some tunnels were so tight, stretchers barely fit through.

Freezing water — Hypothermia was a constant threat.

Communication blackouts — No radios could penetrate that deep, forcing crews to build underground phone lines by hand.

Every few hours, new rockfalls rumbled through the cave, threatening to seal the rescuers inside.

And yet — no one gave up.

For Johann, consciousness came and went in flickers.

He remembered voices — calm, disciplined — speaking to him in clipped German. He felt hands securing his neck, adjusting his helmet, checking his pulse. He could smell earth, sweat, blood.

Rescuers worked in teams of twelve, rotating in and out of the cave like clockwork. It took eight hours just to reach him, another fourteen to move him a few hundred feet.

To keep him alive, doctors performed emergency procedures inside the mountain — monitoring his blood pressure, keeping him hydrated, and warming him with body heat and chemical blankets.

At one point, the tunnel was too narrow for the stretcher. They had to widen it manually — with drills and chisels — one inch at a time.

Outside, the world watched. News crews camped at the cave’s mouth. The story led every major broadcast in Germany and beyond. Millions prayed, waiting for updates that came only once or twice a day.

Every headline read the same:

“3,000 Feet Down — Still Alive.”

On June 19, 2014, after eleven harrowing days underground, the final rescue team emerged into the pale morning light.

At the center of the stretcher — pale, bruised, but conscious — was Johann Westhauser.

Applause and tears broke out among rescuers, doctors, and journalists. The operation had taken 728 rescuers, 12 tons of gear, and over 1,000 man-hours.

And yet, against all logic, Johann had survived.

His first words — quiet, almost whispered — captured everything:

“It’s good to see the sky again.”

That line would be repeated in headlines across the world, from The Guardian to Der Spiegel. It became a symbol of hope — not just for Johann, but for the human capacity to endure.

Johann’s recovery was slow but remarkable. Doctors said he was “lucky beyond measure.” Months later, he walked again.

He refused fame, giving only a few brief statements. “I owe everything to the rescuers,” he said simply. “They risked their lives for me.”

In Germany, he became a symbol — not of tragedy, but of resilience, teamwork, and gratitude. The Riesending cave, once a site of horror, was closed to the public for years afterward, out of respect for the rescue effort.

Rescue teams were honored nationally. The event reshaped how Europe trains for underground emergencies.

And in the small alpine village below, locals still tell the story — of the man who went into the mountain and came back reborn.

There’s something timeless about Johann Westhauser’s story.

It’s not just about survival — it’s about connection. The bond between teammates who refused to abandon him. The rescuers who worked without rest. The strangers who watched and hoped from miles away.

3,000 feet below the earth, in absolute darkness, courage became contagious.

And when Johann finally saw the sky again, the world was reminded of something simple — yet profound:

That even in the coldest, darkest places, human will can light the way home.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load