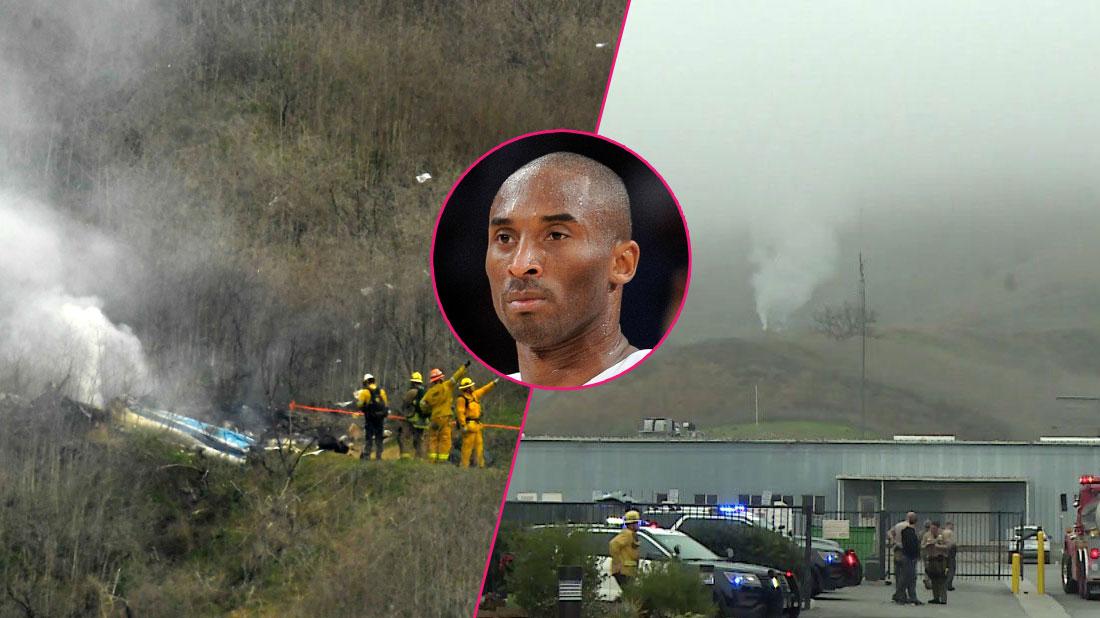

It was a calm Sunday morning in Southern California — quiet skies, soft mist, a cool ocean breeze. Kobe Bryant, the NBA icon turned devoted father, kissed his wife and children goodbye before boarding his private helicopter with his 13-year-old daughter, Gianna.

They weren’t flying for luxury or fame that day. They were simply headed to a youth basketball game — a family routine Kobe loved. But within an hour, that routine would become one of the darkest days in sports history.

At 9:06 a.m., Kobe, Gianna, and six others lifted off from John Wayne Airport in Orange County. Their destination: Camarillo Airport, northwest of Los Angeles — just a 40-minute flight.

They never made it.

What followed was a devastating chain of misjudgments, human error, and weather that conspired to end nine lives — and leave millions around the world in disbelief.

The man in control of the Sikorsky S-76B that day was Ara Zobayan, 50 years old — an experienced, well-liked pilot trusted by Los Angeles’ elite. He’d flown Kobe countless times before. To the Bryant family, Ara wasn’t just a pilot. He was a friend.

He’d logged more than 8,500 flight hours — a number that spoke of skill and discipline. But that Sunday, even experience couldn’t overcome what lay ahead.

The Weather Warning

By dawn, a dense marine layer had rolled across Southern California. The National Weather Service issued warnings of fog, mist, and mountain obscuration — a pilot’s worst enemy. Still, Kobe’s team checked in. The pilot texted back: “Not the best day… but manageable.”

At 9:06 a.m., the helicopter rose into the mist. Inside: Kobe, Gianna, baseball coach John Altobelli, his wife Keri, daughter Alyssa, family friends Sarah and Payton Chester, and assistant coach Christina Mauser.

They had done this route many times — John Wayne to Camarillo, a short hop over the hills. What could possibly go wrong?

The Flight Path

The Sikorsky traveled northwest, following the 5 and 101 freeways — hugging the terrain to stay under the clouds. But as they approached Burbank, the fog thickened.

Controllers warned of IFR conditions — “instrument flight rules,” meaning visibility was too poor for visual navigation.

Zobayan requested a special VFR clearance — permission to continue at low altitude, under the clouds. It was legal. But it was risky.

For 15 long minutes, he circled outside restricted airspace, waiting for clearance. Finally, he got it — and pressed on toward Calabasas, just 25 miles from safety.

At 9:42 a.m., witnesses in the hills of Calabasas heard the low hum of rotors slicing through fog.

Inside the cockpit, the pilot radioed calmly:

“We’re going to start our climb to go above the layers.”

It was his final transmission.

What he didn’t realize — and what radar data later revealed — was chilling.

Instead of climbing, the helicopter was descending rapidly, turning left, nose down.

In dense fog, with no horizon, pilots can become spatially disoriented — their senses tricking them into believing they’re climbing when they’re actually diving.

Within seconds, the Sikorsky plunged at over 180 mph into the hillside of Las Virgenes Canyon, bursting into flames.

There were no survivors.

When first responders arrived, the wreckage was barely recognizable — twisted metal, scorched grass, and silence.

The world stood still.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) spent over a year piecing together what went wrong.

The helicopter itself was in perfect working order. The autopilot and instruments were functional. There was no mechanical failure.

The problem was human.

Investigators found no evidence of external pressure from Kobe or his team to fly that morning — but they discovered something else:

Self-induced pressure.

Zobayan had a long, trusting relationship with Kobe. He wanted to deliver — to “get them there.” It’s a phenomenon pilots call “get-there-itis” — the dangerous urge to continue despite worsening conditions.

He also likely experienced “plan continuation bias”, sticking to his initial route even as visibility dropped to near zero.

And while he was rated for instrument flying, he’d logged only 75 hours of instrument experience in that specific aircraft — with just seven hours in actual weather.

When he entered the clouds, his senses betrayed him. He believed he was climbing. In reality, the helicopter was banking and descending into rising terrain.

It took just 60 seconds from entering the clouds to impact.

News broke within minutes.

TMZ was first. Then every major outlet on Earth.

“Kobe Bryant Dead at 41.”

The words didn’t feel real.

Fans gathered outside Staples Center, leaving flowers, jerseys, and handwritten notes. Murals appeared overnight across Los Angeles, from Venice Beach to downtown.

The world grieved not only a legend, but a father who adored his daughter — who was becoming a star in her own right.

In February 2021, the NTSB released its final report:

“The probable cause of the accident was the pilot’s decision to continue flight under visual flight rules into instrument meteorological conditions, resulting in spatial disorientation and loss of control.”

In simpler words — the fog didn’t kill Kobe Bryant. The decisions did.

But out of the tragedy came lessons — for pilots, for leaders, for all of us.

That no goal, no schedule, no expectation is worth risking a life.

Today, at the site in Calabasas, a small memorial still stands — nine stones for nine souls. Visitors leave purple and gold flowers. Some whisper prayers. Others stand in silence.

The crash was over in seconds, but its echo endures — in every fan who watched him play, every parent who hugged their child a little tighter that night.

Kobe’s final flight wasn’t just an accident. It was a stark reminder of how fragile greatness — and life — can be.

News

Wife Pushes Husband Through 25th Floor Window…Then Becomes the Victim

4:00 p.m., June 7, 2011: University Club Tower, Tulsa Downtown traffic moves like a pulse around 17th and South Carson….

Cars Found in a Quiet Pond: The 40-Year Disappearance That Refuses to Stay Buried

On a quiet curve of road outside Birmingham, Alabama, a small pond sat untouched for decades. Locals passed it…

She Wasn’t His “Real Mom”… So They Sent Her to the Back Row

The Shocking Story of Love and Acceptance at My Stepson’s Wedding A Story of Courage and Caring at the Wedding…

A Silent Child Broke the Room With One Word… And Ran Straight to Me

THE SCREAM AT THE GALA They say that fear has a metallic smell, like dried blood or old coins. I…

My Husband Humiliated Me in Public… He Had No Idea Who Was Watching

It was supposed to be a glamorous charity gala, a night of opulence and elegance under the crystal chandeliers of…

I Had Millions in the Bank… But What I Saw in My Kitchen Changed Everything

My name is Alejandro Vega. To the world, I was the “Moral Shark,” the man who turned cement into gold….

End of content

No more pages to load