The Spear Chuckers: Private Jack Riley and the Forgotten Revolution on Bougainville

Prologue: The Hill of Death

April 14, 1944. 1:47 p.m.

Bugenville Island, Pacific Theater. Private Jack “Hatchet” Riley crouched in a shell crater, gripping a homemade javelin—bamboo shaft, steel tip, wire bindings. Eighty yards uphill, a Japanese bunker had already killed eleven Marines that morning. The air was thick with gunpowder, sweat, and the smell of burning jungle. In the next four minutes, Riley would throw his primitive weapon eight times, pierce eight targets, and trigger a tactical revolution the Marine Corps would try to bury.

The other Marines called him crazy. Officers called him insubordinate. His own squad leader called him a liability. But none of them could throw like Riley could.

Chapter One: Pittsburgh Steel

Jack Riley grew up on Polish Hill in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His father worked the blast furnaces at Jones and Laughlin Steel. The family lived in a two-room apartment above a butcher shop. Jack started working the mills at fourteen, lying about his age. By sixteen, he was thick-shouldered from hauling scrap, his hands calloused from molten slag.

But what defined him wasn’t steel or baseball—it was throwing. Javelin. His grandfather had competed in track and field in the old country, throwing the spear in village competitions. He taught Jack the ancient technique: the run-up, the crossover step, the explosive release. By eighteen, Riley could hit a barrel at sixty yards. By twenty, he’d won amateur competitions across western Pennsylvania.

When war came, the Marines didn’t care about javelins. They cared about rifles, grenades, and following orders.

Riley enlisted in January 1942, three weeks after Pearl Harbor. Boot camp at Parris Island revealed his fundamental problem: he couldn’t follow doctrine he thought was stupid.

“Bayonet charges are suicidal,” he told his drill instructor after watching men stumble through the course.

“You questioning Marine Corps tactics, recruit?”

“I’m questioning running at machine guns with knives on sticks, sir.”

That earned him a week of extra duty—and a reputation.

Chapter Two: The Jungle Meat Grinder

By March 1944, Riley was with the Third Marine Division on Bougainville. The island was a meat grinder. Japanese forces had fortified the interior with interlocking bunkers, spider holes, and camouflaged positions that turned every advance into a bloodbath.

The standard tactic was simple: suppress the bunker with rifle fire, throw grenades, charge with fixed bayonets. It worked in training. It failed in the jungle.

Grenades bounced off tree trunks. They rolled downhill. They detonated too soon or not at all. The Japanese built bunkers with offset firing ports and reinforced roofs. A grenade had to land perfectly inside the narrow aperture—a shot maybe one in twenty Marines could make under fire.

Riley watched men die trying.

On March 28, Private Tommy Sullivan from Brooklyn advanced on a bunker with three grenades. The first bounced off a log and exploded harmlessly. The second landed short. The third caught in a vine overhead. Sullivan was still looking up when the machine gun cut him down.

On April 2, Corporal Jimmy Rodriguez from San Antonio made it within fifteen yards of a bunker. He pulled the pin, threw hard, and the grenade ricocheted off the reinforced entrance. It tumbled back downhill. Rodriguez tried to run. The explosion caught him in the back.

On April 8, Sergeant Frank Kowalski from Chicago led a squad assault on a hilltop position. They threw eighteen grenades. None found the firing port. The bunker killed six men before artillery finally silenced it two hours later.

Riley knew Kowalski. They’d shared cigarettes, talked about Pittsburgh and Chicago, argued about which city had better pierogis. Now Kowalski was wrapped in a tarp, waiting for Graves Registration.

The pattern was clear. Grenades were too unpredictable at range. Marines had to get dangerously close—fifteen, twenty yards maximum—to have any chance of landing one inside a bunker. At that range, Japanese machine guns chewed them apart. Casualty rates for bunker assaults exceeded forty percent. One company lost seventeen men in a single afternoon, taking three positions. The wounded who made it back told the same story: couldn’t get close enough, grenades wouldn’t go in, machine guns too fast.

Chapter Three: The Idea No One Wanted

Riley brought it up to Lieutenant Hargrove after Rodriguez died.

“Sir, we need standoff weapons. Something accurate at fifty, sixty yards.”

Hargrove looked tired. “We have grenades, Private.”

“Grenades don’t work past twenty yards. They’re too light, too unpredictable. Men are dying because we can’t hit bunkers from safe distance.”

“You have a better idea?”

“Yes, sir. Spears.”

Hargrove stared at him. “Spears?”

“Javelins, sir. I can throw one accurately at eighty yards. Straight line, no arc. Fast enough to punch through the firing ports.”

“This is 1944, Private. We don’t fight with spears.”

“We’re dying with grenades, sir.”

“Dismissed.”

Riley saluted and left. That night, he couldn’t sleep. The conversation cycled through his mind, mixing with images of Sullivan looking up at the grenade in the vines, Rodriguez trying to outrun the blast, Kowalski’s body in the tarp.

The regs were clear. Marines used issued equipment. Improvised weapons violated regulations, but the regulations were written by men who’d never watched their friends die because a grenade bounced wrong.

Chapter Four: The First Javelin

On April 11, Riley made his decision. After chow, he walked into the jungle with a machete and a Zippo lighter. He needed bamboo—thick, straight, dense. He found a grove two hundred yards from camp and spent an hour testing stalks. Most were too thin or brittle. He finally cut a section four feet long, two inches thick, nearly hollow at the core.

Back at his foxhole, he worked by moonlight. He carved the bamboo into a rough shaft, then split one end and inserted a sharpened piece of steel he’d pulled from a destroyed truck. The steel was from the suspension—hard, springy, designed to handle stress. He lashed it with wire and tested the balance. Too front-heavy. The weight distribution was wrong. He adjusted, shaving wood from the front half, adding weight to the rear with wrapped wire. He tested it again, feeling the center of gravity. Better. Not perfect, but better.

The whole thing took three hours. His hands were covered in bamboo splinters and grease. The blade wasn’t pretty—crude, asymmetric, more shiv than spearhead. But when he test-threw it at a tree trunk thirty feet away, it hit point-first and stuck deep.

He made three more that night, each one slightly different, learning as he went. Better balance, cleaner lines, sharper points. By dawn on April 12, he had four javelins hidden in his foxhole.

He knew what would happen if officers found them: court martial for unauthorized weapons, possible brig time, definitely removal from combat duty. The Marine Corps didn’t tolerate freelancing. But he also knew what would happen if he did nothing: more men would die trying to throw grenades into bunkers from twenty yards.

Chapter Five: The First Throw

On April 13, Riley carried one javelin on patrol. Nobody noticed. Marines carried all sorts of improvised tools—machetes, clubs, knives made from bayonets. One more piece of bamboo didn’t stand out.

That afternoon, the platoon encountered a Japanese position blocking a supply trail. Standard bunker—logs, sandbags, narrow firing port. The machine gun inside had good fields of fire covering the trail and both flanks.

Lieutenant Hargrove called for volunteers to assault. Three Marines moved up with grenades. Riley watched from forty yards back. The first Marine threw. The grenade hit a tree and bounced left. The second Marine threw harder. The grenade sailed over the bunker. The third Marine got closer, twenty-five yards, and threw straight. The grenade landed in front of the aperture and exploded—dirt and splinters, but the machine gun kept firing.

All three Marines made it back. Nobody died, but nobody solved the problem either. Hargrove called for artillery support. They waited.

Riley looked at the javelin in his hands. Eighty yards, he told himself. Could he really do it? He’d hit barrels at sixty in Pittsburgh, but that was peacetime—no stress, solid ground. This was jungle, mud, adrenaline, and a target eight inches wide.

But the math worked. A javelin flew straight. No arc like a grenade. No bounce. Just velocity and trajectory. If he threw true, it would go where he aimed.

He stood up.

“Private, get down!” Hargrove snapped.

“Sir, request permission to try something.”

“Negative. Artillery’s inbound.”

“Sir, I can hit that port from here.”

Hargrove looked at the bamboo shaft in Riley’s hands, then at the bunker eighty yards uphill.

“With that?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You’re out of your mind.”

“Probably, sir, but I can make the throw.”

Hargrove studied him. Around them, Marines crouched in the underbrush, waiting for artillery. That might take thirty minutes or three hours. The Japanese bunker controlled the trail. Without neutralizing it, the platoon couldn’t advance, couldn’t bring up supplies, couldn’t reinforce positions ahead.

“One throw,” Hargrove said. “Then you get down.”

“Yes, sir.”

Riley moved to the trail edge where he had clear line of sight. The bunker sat uphill at a slight angle, firing port visible but narrow—maybe eight inches high, twelve wide. The machine gun barrel protruded slightly, eighty yards uphill, crosswind from the left.

He adjusted his grip, feeling the balance point. The shaft was rougher than competition javelins, heavier at the front, but the principle was the same. Speed and release angle determined everything. He stepped back six paces. The run-up had to be perfect. Too fast and he’d lose control. Too slow and he’d lose velocity. He needed explosive acceleration at release—his body weight driving through the throw.

Breathing slowed, focus narrowed. The firing port became the only thing in the world.

Three steps, four, five, plant. Crossover, release.

The javelin left his hand at roughly sixty miles per hour, rotating slightly, steel tip forward. It covered eighty yards in just under two seconds. It hit dead center in the firing port.

The impact wasn’t loud—a thunk of metal on wood—but the effect was immediate. Screaming from inside the bunker, the machine gun went silent.

Marines stared.

“Holy shit,” someone whispered.

Chapter Six: Eight Throws That Changed Everything

Riley didn’t hesitate. He grabbed his second javelin and threw again while the Japanese defenders were still reacting. This time, the spear entered at a steeper angle, punching through the firing port and angling downward. More screaming. Then silence.

“Cease fire,” Hargrove ordered, though nobody was shooting.

“Riley, stay here. First squad, advance and clear.”

Four Marines moved up cautiously, grenades ready. They reached the bunker, peered inside, then waved all clear. Hargrove walked up the hill with Riley behind him. Inside, two Japanese soldiers were dead—one hit in the chest by the first javelin, the other in the throat by the second. The machine gun sat unmanned.

“Jesus Christ,” Hargrove said quietly.

Sergeant Mike Dawson from Tennessee picked up one of the javelins and examined it. “You made this?”

“Yes, Sergeant.”

“How far can you throw these?”

“Eighty, maybe ninety yards if I’m throwing downhill.”

Dawson looked at Hargrove. “Sir, this changes things.”

Hargrove nodded slowly. “Private Riley, make more of these. That’s an order.”

“How many, sir?”

“As many as you can.”

That night, Riley worked in his foxhole by firelight, supervised by Dawson. Other Marines gathered to watch. He’d brought more bamboo from the grove, more scrap metal from the motorpool. He carved and balanced, tested and adjusted. By midnight, he had twelve javelins—crude but functional, each about four feet long, steel tips lashed with wire, balanced for throwing.

“Teach me,” Dawson said.

“It takes years to throw accurately.”

“Then teach me to throw adequately. We need more throwers.”

Riley taught him the basics: grip, run-up, release point. Dawson practiced on trees, missing more than he hit, but learning. His military discipline helped. He followed instructions precisely, repeated movements until muscle memory formed. By April 14th, three other Marines had started training. None could match Riley’s accuracy, but they could hit targets at forty yards consistently. That was enough for most bunker engagements.

Word spread through the company without official channels. A private had invented a weapon that worked better than grenades. He could hit bunkers from distances that kept Marines alive. Officers didn’t know whether to applaud or arrest him.

Chapter Seven: Hill 155

1:47 p.m., April 14th, 1944. Second platoon faced a Japanese strong point on Hill 155—a fortified position that had repelled two previous assaults. Intelligence reported multiple bunkers, interlocking fields of fire, and at least thirty defenders. The hill controlled a vital supply route. Taking it was essential.

Lieutenant Hargrove briefed the platoon that morning. Standard assault: first squad suppresses, second squad advances with grenades, third squad exploits. Artillery prep at 1300 hours. Attack at 13:30.

Riley raised his hand. “Sir, request permission to lead with javelins.”

“Negative. This is a company-level assault. We do it by the book. That’s final, Private.”

The assault went exactly as doctrine prescribed. Artillery pounded the hill for twenty minutes. Marines advanced in three waves. Japanese machine guns opened up from concealed positions. Grenades flew, most missing their targets. By 2:15 p.m., eleven Marines were dead. The platoon had gained fifteen yards.

Hargrove crouched in a shell crater, face smeared with mud and frustration. Riley slid into the crater beside him, carrying six javelins.

“I didn’t authorize—”

“Court-martial me later, sir. Right now, let me work.”

Hargrove looked at the hill, at the dead Marines scattered across the approach, at the bunkers still spitting fire. “If you get killed, I’m not explaining this to battalion.”

“Fair enough.”

Riley low-crawled to a position with clear sight lines. The main bunker sat eighty yards uphill, firing port visible between sandbags. Two secondary bunkers flanked it at sixty yards each. Spider holes dotted the slope. He identified targets systematically: main bunker first to eliminate the heavy machine gun, then flanking positions, then individual spider holes. Eight throws if he was perfect, maybe ten if he missed.

He stood, planted his feet, and threw. The first javelin flew true, entering the main bunker’s firing port. Screaming, the machine gun stopped.

Reload. Adjust. Second throw at the left bunker, sixty-five yards lateral and uphill. The javelin hit high but penetrated. Rifle fire from that position ceased.

Third throw at the right bunker—slightly off-target, hit the sandbag wall two inches left of the port, but the impact created enough shock that the defender inside flinched back. Riley threw again, this time through the port. Silence.

Japanese soldiers in spider holes realized what was happening. They began firing directly at Riley, but he’d positioned himself behind a tree trunk that gave partial cover. Bullets chipped bark inches from his face.

Fourth throw at a spider hole forty yards uphill. The soldier inside was exposed from the chest up, firing a rifle. Riley adjusted for the shorter distance, threw flatter. The javelin caught the soldier in the shoulder and drove him backward into the hole.

Fifth throw at another spider hole, fifty yards right. The bamboo shaft bent slightly in flight—improvised weapons were less consistent than factory-made javelins—but the steel tip stayed true. Hit.

Sixth throw at a bunker he hadn’t initially seen, partially camouflaged with palm fronds. Seventy yards, narrow angle. He waited for muzzle flash to confirm the position, then threw. The javelin disappeared into shadow. A moment later, rifle fire stopped.

Seventh throw at a soldier who broke cover and tried to run laterally across the hill—seventy-five yards, moving target. Riley led him by three feet, released, and watched the javelin arc slightly in the crosswind. The soldier went down.

Eighth throw at the last visible spider hole, sixty yards dead center. The soldier inside must have been reloading because he didn’t react until the javelin was already in flight. It took him high in the chest.

Silence spread across the hill like a wave. No machine gun fire, no rifles, no movement.

Marines stared at Riley. He had two javelins left, but no remaining targets. Smoke drifted from the bunkers. Bodies lay motionless in spider holes.

“First squad, advance and clear,” Hargrove ordered, his voice steady.

Marines moved uphill cautiously, expecting resistance. They found eight dead Japanese soldiers, one wounded, and no fight left in the position. The main bunker held two more defenders who surrendered when Marines appeared at the entrance.

Sergeant Dawson walked the hill, examining each target Riley had hit. The javelins protruded from bunkers and spider holes like grotesque arrows. The steel tips had penetrated sandbags, logs, and human bodies with equal efficiency.

“Eight throws,” Dawson said when Riley joined him at the crest. “Eight hits. Eighty yards maximum range.”

“It was the angle, Sergeant. I had high ground advantage for most throws.”

“Forget modesty. You just took a fortified hill with bamboo and scrap metal.”

Chapter Eight: The Ripple Effect

Lieutenant Hargrove reached the summit and looked down at the American positions below. From up here, the kill zone was obvious—three bunkers perfectly positioned to create intersecting fire lanes. A conventional assault would have cost thirty casualties minimum.

“How many did we lose?” Riley asked.

“Eleven before you started throwing. None after.” Hargrove turned to Riley, his expression unreadable. “Private, you just violated about fourteen regulations I can think of off the top of my head. Unauthorized weapons, freelance tactics, ignoring direct orders.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You also probably saved thirty men, maybe more.”

“Just trying to help, sir.”

“I know.” Hargrove pulled out a cigarette, lit it, offered one to Riley. Both men smoked in silence, looking at the carnage below.

“This is going to cause problems,” Hargrove finally said.

“I know, sir. Division’s not going to like that you invented a new weapon without engineering approval. They’re especially not going to like that it works better than grenades. Should I destroy the javelins?”

“Hell no. Make more. Teach more Marines how to throw them. We’ve got three more weeks of fighting on this island. And I’m not sending men into bunkers with just grenades anymore.”

“What about regulations, sir?”

Hargrove smiled grimly. “Forget regulations. I’ll tell battalion it was my idea.”

By evening, the story had spread through the regiment. A private from Pittsburgh had made spears from bamboo and killed eight Japanese soldiers in four minutes without losing a single Marine. Officers didn’t believe it until they walked Hill 155 and saw the evidence.

Chapter Nine: The Training Begins

Captain Raymond Walsh, the company commander, arrived at Hargrove’s position at 1900 hours.

“I need to see this weapon.”

Hargrove handed him one of Riley’s javelins. Walsh examined it—bamboo shaft wrapped with wire for grip, steel tip lashed with more wire, balanced somewhere between front and center. Crude, but functional.

“And your private can throw this accurately at eighty yards?”

“He demonstrated it today, sir. Eight for eight.”

“I want to see him throw.”

They found Riley in his foxhole carving another javelin. Dawson had set up a makeshift range thirty yards into the jungle. Three logs positioned at twenty, forty, and sixty yards, each marked with white paint.

“Private Riley,” Walsh said. “I understand you’re quite the marksman.”

“I can throw straight, sir.”

“Show me.”

Riley grabbed a finished javelin and walked to the throwing line Dawson had marked. He threw three times in quick succession. Twenty yards—dead center. Forty yards—dead center. Sixty yards—slightly high, but still hitting the target. Walsh watched the third javelin quivering in the log.

“How fast can you produce these?”

“Maybe ten per day if I have material, sir. More if other Marines help.”

“How many Marines can you train to throw adequately?”

“Depends on the Marine. Some will pick it up fast. Others might never get accurate past thirty yards, but thirty yards is still better than the fifteen to twenty we’re getting with grenades.”

Walsh nodded slowly. “Private, I’m authorizing you to train anyone who volunteers. I’m also requisitioning bamboo and scrap metal from the motorpool. You’ll have materials for fifty javelins by tomorrow.”

“Sir, there’s likely to be pushback from higher up. This isn’t standard.”

“Let me worry about higher up. You worry about keeping my Marines alive.”

“Yes, sir.”

That night, twelve Marines volunteered for javelin training. Riley taught them in groups of four, focusing on basic form—grip, run-up, release point. He didn’t expect anyone to match his accuracy, but even forty-yard capability would save lives. Sergeant Dawson proved the best student; by midnight, he could hit a log at fifty yards three times out of five.

“Feels wrong,” Dawson said during a break. “Using spears like we’re cavemen.”

“We’re using what works,” Riley replied. “That’s not caveman. That’s smart.”

But the criticism stuck. When other companies heard about the javelins, reactions varied. Some Marines were intrigued. Others mocked it as primitive, ridiculous, unworthy of modern warfare.

“Riley’s spear chuckers,” one corporal called them. “Next, they’ll be throwing rocks.”

Hargrove shut that down fast. “Private Riley took Hill 155 without losing a man. When you can match that with grenades, you can criticize his methods.”

The criticism stopped, but the skepticism remained.

Chapter Ten: The Weapon Spreads

On April 18th, Second Battalion launched a coordinated assault on a Japanese supply depot two miles inland. Intelligence indicated heavy defenses—at least six bunkers, multiple machine gun nests, and an estimated company-sized force. Captain Walsh assigned Riley and three other javelin-trained Marines to First Platoon as an experimental attachment. Their mission: neutralize bunkers before conventional assault.

The approach was through dense jungle, visibility limited to twenty yards. Japanese defenses were positioned on a ridgeline overlooking the depot, creating natural choke points that funneled attackers into kill zones.

At 0800 hours, First Platoon made contact. Machine gun fire erupted from concealed bunkers. Marines hit the dirt. Riley, Dawson, and two other throwers—Private Luis Garcia from New Mexico and Private Thomas “Tiny” Henderson from Alabama—moved forward to assess targets.

The main bunker sat seventy yards upslope, firing port barely visible through foliage. Two secondary positions flanked it at fifty yards each.

“Garcia, take left bunker,” Riley said. “Henderson, right bunker. Dawson, you’re backup for whoever misses. I’ve got center.”

They spread out, finding throwing positions with clear sight lines. The coordination was improvised—no official doctrine for javelin assault—but the logic was obvious. Suppress all positions simultaneously to prevent mutual support.

“On my mark,” Riley called. “Three, two, one—throw.”

Four javelins flew uphill through jungle foliage. Riley’s hit center bunker dead-on, punching through the firing port. Garcia’s hit left bunker high but penetrated the sandbag wall. Henderson’s throw went wide right—nerves and inexperience—but Dawson’s backup throw hit the right bunker perfectly.

Three bunkers neutralized in five seconds.

Japanese defenders in spider holes reacted, firing at the javelin throwers. But Marines with rifles had already moved to flanking positions. Concentrated fire suppressed the spider holes while Riley and his team threw again. Two more hits, two more spider holes silenced. The assault force advanced. First Platoon cleared the ridgeline in eleven minutes with three wounded Marines and no deaths.

After the battle, Major Paul Hendris, the battalion executive officer, inspected the Japanese positions. He counted seven direct javelin hits across three bunkers and four spider holes. Each penetration had been clean—steel tips driven through wood, sandbags, and bodies with enough force to kill or disable.

He found Riley resting against a tree, covered in mud and sweat.

“Private, I need your full name and service number.”

Riley’s stomach dropped. Here it comes—court martial, unauthorized weapons, violation of regs.

“Because I’m recommending you for a Bronze Star.”

Riley blinked. “Sir?”

“Your innovation has saved dozens of lives. That deserves recognition.”

“I appreciate that, sir, but I’m just doing my job.”

“Your job is to follow orders. You invented a new weapon system and trained other Marines to use it. That’s exceptional initiative.”

Hendris turned to Captain Walsh. “Ray, I want this formalized. Get me a report on javelin effectiveness, accuracy, range, casualty reduction. I’m taking this to division.”

Walsh nodded. “Sir, there’s likely to be resistance. This isn’t standard equipment.”

“I don’t care. Marines are dying because grenades don’t work past twenty yards. If javelins work at eighty yards, we use javelins. Figure out the logistics.”

Chapter Eleven: Quiet Revolution

Over the next week, the javelin program expanded rapidly—but quietly. Division never officially approved it. No memorandums were issued. No training manuals written. But word spread through informal channels that a private from Pittsburgh had something that worked.

By April 30th, six companies had javelin-trained Marines. Production was still improvised—bamboo from local groves, steel from wrecked vehicles, wire from communications equipment—but output reached seventy javelins per week. Casualty rates for bunker assaults dropped measurably. Companies using javelins reported 18–22% casualty rates versus 38–45% for companies relying solely on grenades.

The difference was standoff distance. Javelins allowed Marines to engage bunkers from sixty to eighty yards instead of fifteen to twenty. Lives saved—estimates vary, but conservative analysis credits the javelin program with reducing casualties by approximately ninety Marines over three weeks.

Then the Japanese noticed. On May 3rd, an American patrol found a dead Japanese officer carrying a detailed sketch of a Marine throwing what appeared to be a spear. Japanese text annotated the image. Rough translation indicated “new American tactic and long-range penetration weapon.” Intelligence officers were baffled.

“They’re documenting improvised bamboo spears,” Riley said when shown the sketch.

Additional evidence surfaced through prisoner interrogations. Japanese defenders described American attacks using long throwing spears that struck from unexpected distances. Several mentioned seeing Marines with primitive weapons that seemed anachronistic but were devastatingly effective.

Most tellingly, Japanese tactical doctrine began adjusting. Bunkers were repositioned deeper into jungle cover. Firing ports were narrowed further. Some positions added overhead camouflage specifically to break line of sight from throwing positions. The enemy was adapting to counter a weapon that officially didn’t exist.

On May 7th, the Marine Corps quietly acknowledged reality. A classified memo from division headquarters authorized “field expedient standoff weapons for bunker assault” without specifically mentioning javelins. It authorized company commanders to employ innovative solutions developed through operational necessity and requested engineering evaluation of auxiliary anti-bunker systems.

Translation: Keep doing what works, but don’t call attention to it.

No one was court-martialed. No one received official recognition beyond Captain Walsh’s Bronze Star recommendation, which disappeared into bureaucracy and never emerged.

Epilogue: The Forgotten Hero

Riley continued training Marines and producing javelins. By May 15th, when organized Japanese resistance on Bougainville effectively ended, fourteen companies had javelin capability. Estimated production: 340 functional javelins. Trained throwers: sixty-seven Marines. Casualty rate reduction across javelin-equipped units: thirty-one percent.

The innovation worked, but it never became doctrine. After Bougainville, Riley’s unit redeployed to Guadalcanal for rest and refit. The javelins stayed behind, buried in the jungle or burned with other refuse. No one transported them. No one documented them. No one filed reports about their effectiveness.

In June 1944, Riley received orders to report to Headquarters Marine Corps in Washington, D.C. He assumed it was related to the Bronze Star recommendation. It wasn’t.

Colonel James Merritt, a career officer with extensive procurement experience, met Riley in a small office at Marine Barracks.

“Private Riley, I have read the after-action reports from Bougainville. Fascinating reading.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Twelve different officers mention improvised standoff weapons reducing casualties in bunker assaults. Nine mention you specifically, yet there’s no official documentation of what these weapons were or how they functioned.”

“Operational security, sir. Bureaucratic embarrassment.”

“You invented something that works better than issued equipment. That makes people uncomfortable.”

Merritt opened a folder containing photographs of Riley’s javelins, sketches of throwing techniques, and statistical analysis of casualty rates.

“Engineering wants to test your design. See if we can manufacture standardized versions.”

“That’s good news, sir.”

“It would be if they weren’t planning to take six months to do it. By then, the campaign will have moved on. Different terrain, different tactics. Javelins work great in jungle bunker assaults. Less useful in urban warfare or island hopping.”

Riley said nothing. The implication was clear.

“Private, the Marine Corps appreciates innovation, but we also appreciate logistics, standardization, and adherence to established doctrine. Your javelins saved lives. They also created a procurement nightmare. How do we manufacture them, distribute them, train replacements, maintain them?”

“You don’t, sir. You give Marines bamboo and scrap metal and let them make their own. That’s how innovation actually happens in combat.”

Merritt smiled. “That’s not how the Marine Corps works, son. We’re an institution. Institutions need procedures.”

“Men need tools that keep them alive, sir.”

“Agreed. But sometimes those tools don’t fit into neat categories.”

The meeting ended with no clear resolution. Riley was assigned to a training battalion at Camp Pendleton, where he taught small unit tactics to replacement Marines. He mentioned javelins occasionally, but without materials or official support, the concept remained theoretical.

By August 1944, the javelin program on Bougainville was forgotten. Marines who’d used them were scattered across the Pacific. The weapons themselves had rotted in the jungle. No documentation survived in official records. The innovation died.

Riley served in the Pacific until September 1945. He participated in operations on Iwo Jima and Okinawa, where terrain and tactics made javelins impractical. He never threw one in combat again.

After Japan surrendered, he returned to Pittsburgh. He worked construction for two years, then took a job at a machine shop making industrial parts. He married in 1948, had three children, and lived in the same neighborhood where he’d grown up. He never talked about the war. When pressed, he’d say, “I did my job, came home. That’s enough.”

In 1962, a military historian researching Marine Corps innovation stumbled across fragmentary references to standoff weapons in Bougainville reports. He tracked down Riley through veterans organizations.

“Is it true you invented spears, javelins?”

“I didn’t invent them. Greeks had them 3,000 years ago.”

“But you used them against bunkers for about three weeks.”

“Then the brass decided it was too weird.”

The historian published a short article in a military journal. It mentioned Riley’s name once. No follow-up research occurred. The story remained obscure.

Jack Riley died in 1989 at age sixty-seven of heart failure. His obituary in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette ran four paragraphs. It mentioned his service in the Marines, his work at the machine shop, his three children and seven grandchildren. It didn’t mention Hill 155 or javelins or the ninety Marines whose lives he probably saved.

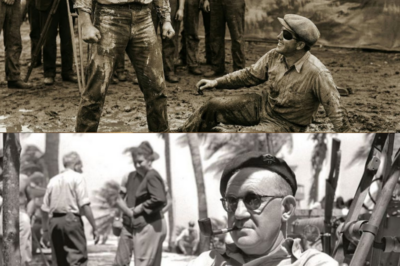

His grandson found a single photograph years later while cleaning out the house—Riley in jungle fatigues holding a bamboo shaft with a steel tip, standing next to Sergeant Dawson. Both men were grinning. The back of the photo read: “Bougainville, April 1944. The spear chuckers.”

That’s how innovation actually happens in war. Not through procurement committees or official channels. Through enlisted men who see problems and solve them with whatever materials they can scavenge. Through Marines willing to risk court martial to save their friends. Through sergeants who look the other way when regulations conflict with reality.

The Marine Corps never adopted Riley’s javelins, but for three weeks in the spring of 1944, they were the most effective anti-bunker weapon in the Pacific Theater. And that private from Pittsburgh who learned to throw from his grandfather, who grew up hauling scrap metal in Polish Hill, who couldn’t follow stupid doctrine even when ordered, saved more lives than most generals.

He just never got credit for it.

News

John Wayne Drop A Photo And A Night Nurse Saw It—The 30 Faces He Could Never Forget

The Faces in the Drawer: John Wayne’s Final Debt Prologue: The Ritual UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, May 1979. The…

John Wayne Refused A Sailor’s Autograph In 1941—Years Later He Showed Up At The Family’s Door

The Mirror and the Debt: A John Wayne Story Prologue: The Request San Diego Naval Base, October 1941. The air…

John Wayne Kept An Army Uniform For 38 Years That He Never Wore—What His Son Discovered was a secret

Five Days a Soldier: The Secret in John Wayne’s Closet Prologue: The Closet Newport Beach, California. June 1979. The house…

John Wayne- The Rosary He Carried in Secret for 15 Years

The Quiet Strength: John Wayne’s Final Keepsake Prologue: The Last Breath June 11th, 1979, UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles. The…

Young John Wayne Knocked Down John Ford in the Mud—What the Director Did Next Created a Legend

Mud and Feathers: The Making of John Wayne Prologue: The Forgotten Manuscript In 2013, a dusty box in a Newport…

John Wayne Helped This Homeless Veteran for Months—20 Years Later, The Truth Came Out

A Quiet Gift: John Wayne, A Forgotten Soldier, and the Night That Changed Everything Prologue: A Cold Night in Santa…

End of content

No more pages to load